|

October 11, 2000

Hibben's words were an introduction to a proposal for "A Center For Undergraduate Life at Princeton," in which he sought "a common ground for campus life at Princeton" where "scattered campus interests" might "gather under the Princeton shield." Sound familiar? Hibben's plea for "common ground" has been echoed time and again throughout the past century by Princeton students, faculty, and administrators. Many would say it has never adequately been addressed. But this fall's opening of the Frist Campus Center may finally bring to an end this decades-long quest for communal space. The avowed mission of the Frist Campus Center, says Paul Breitman, its director, is "to build a sense of community by providing an inviting, inclusive, and exciting gathering place for everyone - undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, staff, alumni, and friends of the university." Breitman, formerly associate dean for student centers and student activities at Rutgers University, was named director of the Frist Campus Center in January. "I had worked with campus centers for 30 years," he says, "but I was new to Princeton. I needed to become a member of the community and get a sense of its expectations." So Breitman, a man of seemingly limitless energy, visited departments, offices, and classrooms, held open meetings, solicited campus-wide opinion, and gave tours to any interested comer at all stages of the building's construction.

Designed by Robert Venturi '47 *50 of Venturi, Scott Brown & Associates, Frist is shaped like a square doughnut. The north side retains Palmer's massive wooden doors and the arched entrance familiar to physics students of old, but also offers two broad flanking entrances to the lower levels of the building, as well as a not uncontroversial entrance arcade set in front of the main building. The south side boasts an entirely new wing - embracing what was the façade of the old Palmer Hall - and a huge window-wall facing Guyot Hall. In effect, there is no longer a front and back, but rather two fronts. But it's what's inside that university officials hope will draw the campus community together: classrooms in which every seat has its own high-speed Internet connection; a movie theater that accommodates 198 on the floor and 43 in the balcony; a lecture hall for 192 that has been restored to its condition at the time of Palmer's 1909 dedication (with the addition of a few 21st-century niceties, such as data and video projection capability, audio systems, and remote-controlled chalkboards). There are study lounges, reading areas, computer clusters, and TV lounges; offices for the Undergraduate Student Government and the Graduate Student Government; work- stations for student activity groups; common areas that include a couple of billiards tables; and space for the Women's Center, the International Center, the new Community Service Center, and the Orange Key Guide Service. (Orange Key tours will now start from Frist rather than from Maclean House.) Frist also offers conveniences such as a mailing service, a U-Store branch, cash machines, and a ticket office for on-campus events. Upperclass mailboxes are located on the first floor. Also featured in the center are faculty offices, administrative offices, and classrooms for the Near Eastern Studies and East Asian Studies departments; the language lab; an expanded Gest Oriental Library, and a suite housing the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning. Frist's blending of academic and nonacademic environments may be unique among college centers nationwide. Interior decorative elements include, on the lower level, brightly painted walls drawn with "institutional graffiti" - quotes from famous Princetonians lettered on the brick. "Ants are so much like human beings as to be an embarrassment" comes from Lewis Thomas '33, while Adlai Stevenson '22 offers, "Before you leave, remember why you came." Display cases adorning a staircase feature documents and artifacts relating to Princeton student life. And on a stairwell leading down from the original Palmer entrance will be an orange-and-black plaque inscribed with the names of everyone who participated in the 250th-anniversary campaign. The 58,455 names, inscribed in no particular order, should provide some 77 percent of alumni with an excuse to spend hours in Frist, searching for their piece of Princeton immortality. The plaque will be installed in the spring. No doubt the main attraction of the center, however, will be the food. A food gallery, operated by Princeton's Dining Services, offers a Mongolian Grill, a deli, a salad bar, stations providing vegetarian and various ethnic cuisines, and, oh yes, pizza. Dining Services also runs a café and what is called the Beverage Lab, a small space offering smoothies and other drinks - including alcoholic ones to those over 21 - light food, and a couple of TVs. Students can pay for food at all of these spots with points on their ID cards. They can also sign up for a full meal plan - from six meals a week up to a full 20 - making Frist perhaps Princeton's first legitimate, non-cook-it-yourself, upperclass dining alternative to the eating clubs since 1856. ean of the School of Architecture Ralph Lerner commented in 1993, "Princeton is extraordinarily rich in numerous, wonderful private spaces, yet surprisingly poor in its number and type of truly public spaces." With Frist in operation, Lerner's observation may no longer apply. Yet, spectacular as is the new Frist Campus Center, director Breitman himself points out, "Buildings don't create community; people do." It is the search for community, not only for expanded facilities, that has fueled the campus center movement over the years. Hibben was not the first nor the last Princeton president to experience rising enrollment and an increasingly complex society, or to wring his hands over the divisiveness of the eating clubs; little wonder that the pressure for a campus center has continued on the Princeton campus - much of it initiated by students. The 1954 dedication of the Chancellor Green Student Center itself was the result of several years of fundraising and student activism. "The Campus Center at Princeton," an undated brochure signed by William M. Ruddick '53, solicits support and pleads for "a unifying facility . . . a 'room' in the Princeton household." A Daily Princetonian of the period lamented "severely compartmentalized" campus life. Barry Langman '90, who chaired the USG's undergraduate life committee in 1989, participated in a vociferous "Campus Center Now" movement because, he says, "I believed (and still believe) that one of Princeton's greatest strengths and greatest weaknesses is the way it creates microcosms. Given the multiplicity of ethnic- and interest-based student groups - which in general add so much to student life - Princeton can start to feel Balkanized." And according to one junior, many current undergraduates continue to find Princeton "pretty fragmented." One of the groups most eager to be included in campus life is Princeton's graduate student body. "For years," says Lauren Hale, a graduate student in the Woodrow Wilson School, "graduate students have felt segregated from undergraduate students." There's more than geography at work, believes Hale, who chairs the Graduate Student Government (formerly the Graduate Student Union): "Graduate students have to pay to attend sports events, and undergraduates don't. Undergraduates have access to our dorms with their prox cards, but we don't have reciprocal access to their dorms." Hale hopes that the Frist Center will mitigate "some of these social imbalances." More important, she says, is that Frist might become "a comfortable environment in which graduate students can relax, and interact with the undergraduates." She notes, "The GSG will have a nice office with desks and file cabinets. We will be working near the USG, sharing a common conference room. "I hope the Frist Center works," she says. "A lot of energy has gone into it." The current project took a giant step forward with President Shapiro's 1993 strategic planning report, Princeton University - Continuing to Look Ahead. In that document, Shapiro wrote, "I concur in the broad consensus that has emerged at Princeton over recent years that the time has come to construct a new campus center . . . that . . . would serve and bring together students (graduate as well as undergraduate), faculty, and staff, as well as alumni, parents, and other visitors to the campus." Vice president and secretary Thomas Wright has been involved in the project since its inception. He says that, though the impulse to create a campus center has existed for many years, there have also been various forces militating against it. "For example, there was a period when the eating clubs and their graduate boards saw a center as something that would adversely affect membership; more recently, they have come to see the center, in its present location, as a connecting link to the campus rather than something that could draw members away." Similarly, he says, "For a time, the residential colleges and masters were ambivalent, seeing the center as a possible threat to internal cohesion; now, the colleges are well established and the center is seen simply as an enhancement to student life." Michael Jennings hopes Frist will be just that. Chair of the department of Germanic languages and literatures, Jennings served on several Frist-related committees, including the most recent Campus Center Committee. "I really hope that the center will serve the entire constituency implied in its name," Jennings says. "Princeton needs a focal point for the thousands of directions in which people run, and this should be it." After the years of planning, the campus climate seemed favorable at last in the late 1990s. When, in 1997, the Frist family - including Tennessee senator and university charter trustee William Frist '74, his brother Thomas Frist Jr., and the latter's two sons, Thomas III '91 and William '93 - gave the $25-million gift that made the project financially feasible, everything fell into place. Wright remembers Shapiro commenting, "At a certain point, the stars must have aligned." The Frist Center clearly represents the culmination of years of thought and effort on the part of several generations of students, faculty, alumni, and administrators. Is it perfect? Probably not. Will it instantly meld Princeton's previously "fragmented" environment into one community? Probably not. Still, in this autumn

of 2000, there is hope that eventually, as one senior says, "the

Frist Center will be a place everyone on campus can call home."

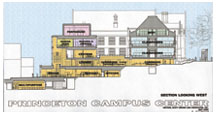

Princeton writer Caroline Moseley is a frequent contributor to PAW. This cross-section of Frist Campus Center, shown as if looking at the center from Washington Road, shows how the new building incorporates Palmer Physics Lab (right and rear of drawing).

B Level: Multipurpose room A Level: Food Gallery; dining room with seating for 270; private dining room 100 Level: Café with seating for 150; Beverage Lab; 3 lounges; Welcome desk; Ticket office; 2 billiards tables; U-Store branch; convenience store; upperclass mailboxes; mail services; ATM machines, pay phones, and e-mail terminals 200 level: Student government offices; Near Eastern Studies and East Asian Studies classrooms and offices; Women's Center; International Center; Community Service Center; 6 seminar rooms; common areas, 4 computer clusters 300 Level: Film and performance hall with seating for 241; 192-seat lecture hall; McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning; Gest Oriental Library (2 stories); 4 seminar rooms; reading room; computer cluster 400 Level: Gest Oriental Library; theater balcony and dressing rooms On the Web: www.princeton.edu/~frist

|

||

In

1926, Princeton president John Grier Hibben, Class of 1882, wrote,

"Everywhere in America, increased student enrollment and a

growing complexity of college life which has kept pace with the

life about it, has presented the same problem: how to centralize

and integrate undergraduate life."

In

1926, Princeton president John Grier Hibben, Class of 1882, wrote,

"Everywhere in America, increased student enrollment and a

growing complexity of college life which has kept pace with the

life about it, has presented the same problem: how to centralize

and integrate undergraduate life."  The

building, which opened in September and will be officially dedicated

October 20, is worth a tour. The six-level, $48-million Frist Campus

Center, constructed in and around a gutted and renovated Palmer

Hall, combines, in the words of President Shapiro, "old charm

and new technology." Architectural elements of the original

Palmer Physics Lab remain to speak of Princeton's history, enhanced

and vastly expanded into the current 185,000-square-foot space.

The

building, which opened in September and will be officially dedicated

October 20, is worth a tour. The six-level, $48-million Frist Campus

Center, constructed in and around a gutted and renovated Palmer

Hall, combines, in the words of President Shapiro, "old charm

and new technology." Architectural elements of the original

Palmer Physics Lab remain to speak of Princeton's history, enhanced

and vastly expanded into the current 185,000-square-foot space.