|

October 25, 2000

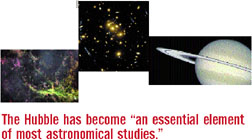

By Billy Goodman It's the most diverse scientific tool ever, one astrophysicist claims: "There's no area in astronomy where it has not done something like no other instrument before it." It's the Hubble Space Telescope, and it is largely the vision of one man. In 1946, Lyman Spitzer wrote a paper entitled "Astronomical Advantages of an Extra-Terrestrial Observatory." Classified despite its seemingly innocuous title, this paper by the 32-year-old Yale physics professor was the first to lay out in detail the advantages of putting a telescope in space. Spitzer, who earned his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1938, returned to the university in 1947 to become chair of the department of astrophysical sciences. For the next 50 years he worked tirelessly, first to make an orbiting telescope a reality, then to do good science with it. He died in March 1997 after a full day working on a paper that used data from the Hubble Space Telescope. Pictured: Photos taken with Hubble include, from left to right, a detailed look at the Crab Nebula; gravitational lens system CL0024+16, taken by Princeton professor Ed Turner; and the richly colored rings of Saturn.

Spitzer had "unparalleled vision and a penetrating, logical mind," says provost and astrophysicist Jeremiah Ostriker. John Bahcall, an astrophysicist at the Institute for Advanced Study and a visiting lecturer at Princeton, says that "Lyman liked to think about big projects, big ideas, and big things. It wasn't that the advantages of a space telescope weren't obvious to everyone, just that no one dared to think about them other than Lyman. He was generations ahead of his time. He didn't get confused by the trees, but saw the forest very clearly." The Hubble, says Ostriker, "has changed cosmology from being a theoretical science to being an empirical one. We observe directly the evolution of the universe and compare theories of what might have been with what we actually see with our eyes." Spitzer's 1946 paper didn't receive an immediate reaction. After all, it was still 11 years before Sputnik and 12 before NASA. But by the 1960s, the idea of astronomy from space was taking hold, and Spitzer continued to be its chief advocate, chairing the National Academy of Sciences' Ad Hoc Committee on the Large Space Telescope later in the decade. Still, astronomers were not unified in support of a space telescope. Some feared the cost would stifle support for ground-based astronomy. Others supported space astronomy but wanted to begin by putting small telescopes in orbit to gain experience. NASA, however, wanted big, showy projects to increase its prestige and to show up the Soviets. By the early 1970s most of the astrophysical community supported a space telescope - in no small part because of Spitzer's advocacy. By 1972 the project was part of the NASA bureaucracy, and a project scientist was selected. (Spitzer, the obvious choice, did not want to leave Princeton for Huntsville, Alabama, where the project was then based.) Teams of scientists were recruited to begin to define what the space telescope would look like and what kind of instruments it would carry. There was strong pressure from NASA to keep the cost down - a projected cost of $700 million in 1972 was deemed too much. Pressures from politics and economics almost overwhelmed the space telescope in 1973 and subsequent years. The Arab oil embargo of 1973 marked a period of severe budget-cutting in Washington. President Nixon's support wavered as he faced the Watergate hearings and eventually left office in 1974. In June of that year, the House appropriations committee recommended that all planning funds for the telescope - $6.2 million - be cut from the budget, and the full House passed a fiscal 1975 appropriations bill with no money for the telescope. Spitzer and Bahcall, who were both heavily involved in NASA's Science Working Group for the telescope, swung into action. There was not a strong precedent for scientists to lobby in Washington on behalf of big science projects, but Spitzer and Bahcall recognized the need and were prepared to do it. Together and separately they visited congressional offices, meeting with staff and some congressmen, in an effort to turn the tide by getting the Senate to reinstate the telescope funds and then work out a compromise in conference to retain them in the final bill. In an oral history interview conducted in 1983 for the Space Telescope History Project of the National Air and Space Museum, Bahcall remembers using whatever means necessary to arrange meetings on Capitol Hill. "We would just evoke the name of Old Nassau or whatever, wherever we thought it would do us any good so, if anybody had a Princeton connection, Lyman would wave the Princeton flag and get us in." Bahcall and Spitzer succeeded in winning a reprieve for the telescope, as some of the $6.2 million was restored to the budget that year. In subsequent years, they would be called on again to defend the Space Telescope against Congressional and agency budget cutting. Like any observatory, the telescope was to have a staff, in this case called the Space Telescope Science Institute. Five groups - four consortia of universities and one private company - bid for the Institute. Each included a proposed site. Princeton, with one of the world's most highly regarded astrophysics departments and home to Spitzer, Bahcall, Ostriker, and numerous others, tried to be named as the preferred site on all five bids. It was eventually named on three. One consortium chose Johns Hopkins University. Princeton's proposed site was on Alexander Road, near the golf course, between the Institute for Advanced Study (which was part of the bid) and the main campus. At first, Institute for Advanced Study members were somewhat less enthusiastic than Princeton faculty over the prospect of hosting the space telescope institute, concerned they would have to share an already overcrowded cafeteria and housing. But cafeteria crowding became moot when in January 1981 NASA chose the bid that located the institute at Johns Hopkins. The decision surprised the Princeton astrophysicists. "Princeton had one of the great astronomy departments in the world," says Bahcall; Johns Hopkins had a much smaller, less distinguished department. Spitzer was especially disappointed, as he related in a 1984 interview for the Space Telescope History Project: "It seemed the logical climax to my own career, having pushed the Space Telescope for umpty-ump years, to have it here at Princeton, and the recognition." Ultimately, Princeton's astronomers came to regard the decision as better for themselves and for their field. Bahcall believes that the special character of the department - a highly productive, elite place - would have been swamped by the huge institute, which now numbers several hundred astronomers, technicians, and others. Ed Turner, a professor of astrophysics who came to Princeton in 1978, says that in hindsight it may not have been good for astronomy to put the space telescope institute in Princeton. "By going elsewhere, the rest of the astronomical community may have seen it as belonging to all of us," he says, thus ensuring wider support for the telescope. Indeed, scientists from all over the world have used and been awed by Hubble's powers. Named after renowned astronomer Edwin Hubble (who discovered that the universe is expanding), the telescope was deployed in 1990 by the space shuttle. After a rocky start - its flawed principal mirror had to be fixed by astronauts in 1993 - the Hubble has become, as Bahcall notes, "an essential element of most astronomical studies." Princeton astronomers have continued to be involved with the telescope, both as active scientific users and in various management roles. Spitzer, whose portrait hangs in the Spitzer conference room of the Space Telescope Institute, was the first chairman of the Space Telescope Institute Council, a sort of board of directors for the observatory. Shortly after Riccardo Giacconi was chosen to be the Institute's first director, he recruited Neta Bahcall to create a guest observer program. Bahcall, John Bahcall's wife, was a Princeton research astronomer at the time - she's now a professor of astrophysics - and recalls commuting back to Princeton on weekends to be with her family. She remained at the Institute until 1989, building a program for soliciting, reviewing, and funding proposals and allocating time on the telescope. Today, astrophysics department chairman Scott Tremaine chairs the time-allocation committee for the next cycle of Hubble observations. He will direct a process that winnows nearly 1,000 proposals to 200 or so accepted projects. In his own research, Tremaine works with a large team looking for evidence of very massive black holes in the centers of galaxies, which are thought to be the power source of quasars in some distant galaxies. Black holes can't be seen directly, but the space telescope, with better resolution than ground-based ones, allows astronomers to look to the center of galaxies for evidence that the movements of stars are being influenced by a massive dark object at the center. Professor Ed Groth, a member of the gravity group in the physics department, was involved in space telescope planning in the 1970s and became a coprincipal investigator of one of the telescope's original instruments. He continues to work with others using Hubble data to try to pin down a key astrophysical number known as the Hubble constant, which is related to the age and size of the universe. (The Hubble constant is widely debated in astrophysics, and estimates vary by almost a factor of two; Groth's group pegs the constant toward the lower end of the range, which results in a larger, older universe.) One of Hubble's current instruments was developed by a team of astronomers that included as coprincipal investigator Ed Jenkins, research astronomer in astrophysics. Jenkins and postdoc Todd Tripp then used the tool, called the Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph, to verify a theory developed by Ostriker and others that there should be lots of hot, hard-to-detect hydrogen gas in between the galaxies. After 10 years in orbit, says John Bahcall, the Hubble Space Telescope is now a unifying force for the field of astronomy, as researchers use it to help them answer some of the big questions in the field. It's the best tool there is, says Turner, for looking at distant and faint objects in the universe. Hubble has also proven to be an effective tool to reintroduce the public to cosmology, as its vivid and dramatic pictures find their way into mainstream media. Originally planned for

a 15-year mission, NASA and researchers hope that Hubble will remain

productive till 2010. Meanwhile, Princeton astronomers continue

to innovate, as more than a dozen are collaborating on the Sloan

Digital Sky Survey, which has begun an ambitious project to map

one-quarter of the entire sky, providing insights to key questions

of the origin and evolution of structure in the universe.

Billy Goodman '80 is a science writer based in New Jersey.

On the Web: Space Telecope Science Institute: www.stsci.edu NASA: www.nasa.gov Sloan Digital Sky Survey: www.sdss.org

|

||

The

Hubble could easily have been called the "Lyman Spitzer Telescope."

In fact, for many years during its long gestation the instrument

was known by the initials LST - which stood not for Lyman Spitzer

Telescope, as some suggested, but for Large Space Telescope. The

instrument is about the size of a school bus, with a 94-inch primary

mirror at the base of a light-gathering tube, and with scientific

instruments arrayed around the periphery. The Hubble's main mirror

is much smaller than some of the recent large ground-based telescopes

that have been built, but it has unparalleled advantages by being

some 300 miles high in orbit around the earth. Chief among these

are the ability to detect wavelengths of radiation that are absorbed

by the atmosphere and improved resolution of images because the

shimmering atmosphere doesn't interfere.

The

Hubble could easily have been called the "Lyman Spitzer Telescope."

In fact, for many years during its long gestation the instrument

was known by the initials LST - which stood not for Lyman Spitzer

Telescope, as some suggested, but for Large Space Telescope. The

instrument is about the size of a school bus, with a 94-inch primary

mirror at the base of a light-gathering tube, and with scientific

instruments arrayed around the periphery. The Hubble's main mirror

is much smaller than some of the recent large ground-based telescopes

that have been built, but it has unparalleled advantages by being

some 300 miles high in orbit around the earth. Chief among these

are the ability to detect wavelengths of radiation that are absorbed

by the atmosphere and improved resolution of images because the

shimmering atmosphere doesn't interfere.