October 24, 2001: Features

Photos,

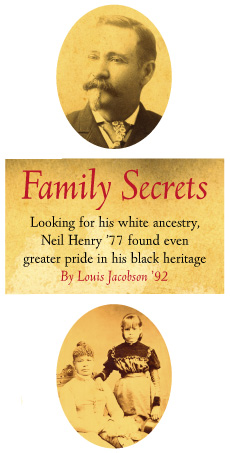

top, A. J. Beaumont; bottom, Laura Brumley and Pearl, ca. 1890. Photo

of Henry by Mimi Chakarova

Photos,

top, A. J. Beaumont; bottom, Laura Brumley and Pearl, ca. 1890. Photo

of Henry by Mimi Chakarova

Neil Henry ’77, a professor of journalism at the University of California at Berkeley, attracted national attention for his recent book, Pearl’s Secret: A Black Man’s Search for His White Family (University of California Press).

Henry, who is African American, spent several years trying to piece to-gether the story of the white descendants of A. J. Beaumont, a white Southerner who fathered a child with Laura Brumley, a former slave, in 1877. That child, Pearl Brumley, was Henry’s great-grandmother. Henry’s family knew of their white lineage only through a few tantalizing documents that had been passed down from generation to generation. Eventually, Henry located a living descendant of Beaumont in Louisiana. He met her in early 1998.

Henry began teaching journalism after a decade and a half reporting and editing for the Washington Post. He now lives in Davis, California, with his wife, Letitia, and daughter, Zoe. Henry spoke with Louis Jacobson, a frequent contributor to PAW. Following are excerpts from that conversation. The full text of the conversation is available on PAW Online.

How long had you tried to write this book?

All of the questions derived from childhood. They were mysterious questions that had perplexed me for a long time, but I didn’t know that it was possible for me to answer them until I became a journalist. My real focus began around 1986 or so, when I had worked as a writer for the Washington Post for about eight years. On a visit home to Seattle I happened to focus again on a number of documents — Beaumont’s obituary; the letter he wrote shortly before he died acknowledging to his mixed-race daughter that he was her father and apologizing that he hadn’t done better by her; and his photograph — that had carried through so many decades in my family’s possession.

When you first made contact with your cousins, how cooperative were they?

Well, it took a long time to get to that point. I did research at the National Archives, in microfilmed newspapers, and in Civil War-era records in courthouses in Mississippi and Louisiana. It was then that I finally learned that the white branch of my family had survived through all of those years. And I finally placed that family with a name — Rita Beaumont Pharis, a woman in Pineville, Louisiana. For a long time, I gestated about how I should approach her. In the phone conversation, she was guarded at first — as you might expect — when I told her about our connection. But when I told her that I had these documents testifying to her grandfather’s relationship with a former slave, and that I had information that even she didn’t know, she became exhilarated.

Were you surprised by her positive response?

Well, you know, all throughout the time I was doing the research, wondering why I was doing it in the first place, I couldn’t help but imagine or fantasize about who I would find. What were they doing? What were their lives like? What kind of jobs would they have? And most important, what kind of people were they? So I imagined all the different kinds of possibilities — that they would hang up the phone, or refuse to speak to me. But it turned out to be a very human response. Rita was somebody who was fascinated by the story I had to tell. So even though we came from different paths — me from a black past, her from a southern, conservative, white path — there was a human connection.

Do you think that the white family you eventually found would have preferred not to know about your branch of the family?

It’s a very good question. Rita’s grandfather was my great-great-grandfather, a white Englishman who immigrated to America in search of a dream like so many immigrants, and he left, as many white men have done in this country, a dual racial lineage. Her family did know that he’d had this relationship before he married a white woman, but they always thought that it had been with an Indian woman. That was the way their father wanted that relationship to be remembered, if it was going to be remembered at all, because where they came from, an Indian was considered higher on the yardstick of humanity than a black person.

But their memory of this person was always kind of vague. I think in Rita’s case, she was profoundly thankful that I made this connection, because, as the book points out, she was going through a very difficult time when I first made that call. My contacting her in that way made her profoundly happy, because she was learning something new.

What about you? How has it changed you to know for sure that you have white cousins?

Ultimately, there were three lessons for me in finding them. One was my appreciation and recognition of the value of journalism as a calling, because it was through the skills I had acquired that I was able to solve these mysteries. Second, I became much more proud of my parents’ generation and the strides they made in American society, and their professional class in particular, in fields like medicine and law. It’s their story that I tell in this book.

Last, and perhaps most important, is the lesson I learned about irony and surprise in life. Despite the stereotypes of race in this country, readers of the book learn about a black family that overcame hurdles to achieve success all over the country, while they meet a white family that was living atop the splendor of white supremacy in the 19th century before suffering a terrible fall. This was the kind of story that stereotypes about race cannot tell. The ultimate irony, for me, was that in looking for traces of my white ancestry, I came away with a much deeper sense of pride in my African-American heritage.

You call your college years “dismal.” What were some of the low and high points?

After my sophomore year, I was kind of aimless, even though I had succeeded academically. I was disappointed with the architecture program, so I took a year off from school and worked on the waterfront in Seattle. I managed to get on a trip to China with a group of writers and artists. This was 1975, only a few years after Nixon first visited, so it was still a profoundly closed society. It was a wonderful experience — it was my first time out of the country, we traveled to all these places, and I kept a journal. I came back and wrote an article for the newspaper in Seattle. It was published — my first byline. So when I went back to Princeton, I declared my major as political science and went to see if I could go back to China through Princeton-in-Asia. A man there looked at me and noted that I was a black person. He said they had never had a black person in the program, and he wanted me to rethink it, because it could cause problems with the host family in Asia. My way of dealing with racism from the time I was a little kid was to swallow it and move on to something else. But it was still a very painful, embittering experience that I’ve remembered to this day.

Next to me in the yearbook you’ll see no photograph and no list of activities. I was profoundly intimidated by the culture. This was a new age of integration at Princeton, and as a black person, I didn’t feel particularly welcome. I think there were other black people of that time who would tell you the same thing — that we were there as kind of an afterthought. So when people ask me what class did I belong to, I say, “I was part of the invisible class.”

But the reason I was there was to get as much as I could out of the university, and that meant academic learning. There were individuals at the university who were helpful to me in a way that had a lasting effect on my life. But on the whole, as I say in the book, one of my memories was my alone-ness.

Louis Jacobson ’92 is a staff correspondent with National Journal magazine.