December 19, 2001: Features

Of

Friends and Strangers

Of

Friends and Strangers

Two Princeton friends, generations

apart, made remarkable discoveries through an emotional, Oscar-winning

documentary

By Kathryn Levy Feldman ’78

Photo captions:

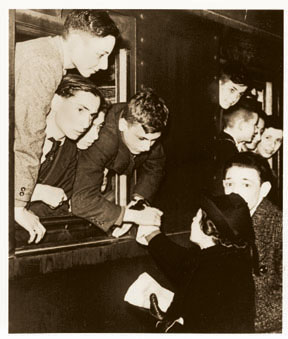

Kinder are greeted by Dutch women at the border, a photo from the documentary "Into the Arms of Strangers"

Michael Steinberg ’49 *51, left, and Alicia Dwyer ’92 attended the film’s London premiere together.

There is a Yiddish term “bashert” that is loosely translated as “fate” or “meant to be.” It is often used to describe circumstances so coincidental that they defy rational explanation. This is the story of two Princeton alumni whose relationship can only be described as “bashert.” Though they graduated more than 40 years apart, the Princeton connection that brought them together was truly meant to be.

After graduating from Princeton in 1992 with a double major in German and politics, Alicia Dwyer moved to San Francisco. Through Princeton, she obtained a list of alumni in the Bay Area who were willing to serve as mentors to graduates interested in pursuing careers in the arts. Dwyer wrote to two names on the list and received a phone call from one, Michael Steinberg ’49 *51. At the time, Steinberg, who had earned both his undergraduate and graduate degrees in music, worked for the San Francisco Symphony writing program notes and lecturing on music.

From

the moment they met, Dwyer and Steinberg hit it off. “He was delightful,”

Dwyer says. “He would take me to brunch, and we would discuss art,

music, and Princeton, often in German.” Steinberg was originally

from Germany, and Dwyer had lived in Berlin as a teenager. Even though

Steinberg almost succeeded in getting Dwyer a job with the San Francisco

Symphony, the premise behind their relationship became incidental. “A

thin, but firm string held us together,” recalls Steinberg. “We

had a mutual liking for each other, and she was turning into one of my

few friends not involved with classical music.”

From

the moment they met, Dwyer and Steinberg hit it off. “He was delightful,”

Dwyer says. “He would take me to brunch, and we would discuss art,

music, and Princeton, often in German.” Steinberg was originally

from Germany, and Dwyer had lived in Berlin as a teenager. Even though

Steinberg almost succeeded in getting Dwyer a job with the San Francisco

Symphony, the premise behind their relationship became incidental. “A

thin, but firm string held us together,” recalls Steinberg. “We

had a mutual liking for each other, and she was turning into one of my

few friends not involved with classical music.”

After some consideration, Dwyer decided to pursue a career in film and moved to Los Angeles to enroll at the University of Southern California. Steinberg also relocated, to Minneapolis, where his wife accepted a position as concertmaster with the Minneapolis Symphony. The two Princetonians remained in touch, mainly through holiday cards and occasional phone calls.

Fast-forward six years. Having graduated from USC film school, Dwyer was working for one of her former teachers doing research for a film. Steinberg had written what Dwyer describes as a “grand book about symphonies” and was lecturing around the country.

“I happened to write Michael a holiday card in the winter of ’98 and mentioned the projects I had been working on,” Dwyer recalls. “I went into great detail about the research I was doing on something called the Kindertransport, a rescue operation in which Britain saved 10,000 mostly Jewish children from Nazi Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia in the nine months before World War II started.” As soon as he received her card, Steinberg called.

“Did you know that is how I got out of Germany?” he told his friend. “I was on one of those trains. I was one of those children.”

n November of 1938, at a time when emigration to most other countries was virtually nonexistent because of strict quotas, Britain opened its doors to 10,000 children at risk from the Nazi regime. Spurred by Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax, who thought Britain’s act of generosity might set an example for other countries, the British cabinet agreed to accept, on a temporary basis, unaccompanied refugee children under the age of 17. Numerous refugee agencies, including the Quakers, the Jewish Refugees Committee and Inter Aid, a Christian organization associated with the Save the Children Fund, agreed to fund the operation (every child would have a £50 guarantee paid against their re-emigration) and provided the infrastructure for selecting, processing, and transporting the children. British families volunteered to serve as foster homes. The first train loaded with “kinder” left from Berlin on December 1, 1938. The operation ended in late August 1939, just before the war broke out.

At the time of Steinberg’s call, Dwyer had spent 10 months interviewing former “kinder,” foster parents, rescuers, and parents for a documentary entitled Into the Arms of Strangers. Narrated by Dame Judi Dench, the full-length documentary (associate-produced by Dwyer) recounts the remarkable rescue operation that had saved her friend’s life. Never did she suspect that her Princeton mentor could have been one of her subjects. “We had had conversations about his background, and I knew that he had grown up in Germany and spent some time in England, but I never made the connection,” she says.

Much to Dwyer’s delight, Steinberg had in his possession one of the only photographs of a Kindertransport child in a train. According to Steinberg, the photo — which appears in both the film and the book by the same title — depicts him and another boy (who, he recently learned, is living in Mill Valley, California) “framed in a train window, looking cheerful as could be, our minds set on adventure, with my mother in deep mourning and a family friend out on the platform of the Berlin-Charlottenburg station.” Steinberg’s mother (his father had died a few months earlier) and her friend had put the 10-year-old on the train at the easternmost Berlin station, the Schlesische Bahnhof, and then taken another train to the westernmost station, where the photo was taken for a final farewell. “I am sure that for many of my traveling companions these station farewells were literally the final ones,” Steinberg says.

When Steinberg left his German town of Breslau on May 2, 1939, Hitler had been in power for six years. As a young boy, Steinberg witnessed “Kristallnacht” in November 1938, when synagogues were burned, stores were looted, and Jewish men were rounded up and shipped to concentration camps. His much older brother, Franz, had already left Germany for Switzerland a few years earlier to continue his medical studies when he was denied access to the University of Breslau. “I had no clear idea of the life I was heading for,” Steinberg says, but “I knew why I was leaving.”

The Quakers matched Steinberg with a family by the name of Layng who lived in the English village of Stapleford, just outside Cambridge. Peter and Elizabeth Layng had two daughters and an adopted son; the son and one daughter were Steinberg’s age, the other daughter two years younger.

Although there was an inevitable adjustment period, Steinberg has nothing but fond memories of his adopted family and the five years he spent with them in the English countryside at “Three Ways.” (“That was another oddity,” he recalls. “Houses with names instead of numbers.”) “I remember Peter as immensely kind in those first three weeks before I was packed off to boarding school and during which, I was told later, I smiled a good deal, seemed content enough, and was all but totally silent,” he says. In his silence, he explains, he was learning English and at some point began to chatter away, “incorrectly and fluently.” He got along famously with his “siblings” and maintains a relationship with them to this day. “We, ‘the young,’ were a complex and resourceful mutual entertainment center and we hardly ever fought, not out of repression, but genuinely having no need to,” he recalls. He remembers long bike rides, clambering up and down the local chalk pits, punting on the River Cam, playing word games and “hours and hours of Monopoly — with London street names — briefly whist and then lots of bridge.”

Not all “kinder” fared as well as he did. Many were taken in by families whose resources were meager, and numerous German children were subject to living in homes without central heating and indoor plumbing. Still more were detained in makeshift, often primitive, refugee camps until accommodations could be arranged. Some teenage girls were taken in to serve as maids and had to fend off sexual advances from their employers. Most never saw their parents again.

Steinberg, however, was extremely lucky. About three months after he left Germany, his mother, as he tells it, “spurred by urgent (though necessarily cryptic) messages from my Uncle Erich in London, suddenly decided one afternoon to pack a small suitcase, lock the apartment behind her, take a taxi to the station and head for England too.” She settled in Cambridge, although not with her son, who remembers she lived “first in various shared apartments and then in a flat of her own.” They visited on Sundays.

During the five years they spent in England, Steinberg’s mother continued to apply for papers to immigrate to America, specifically St. Louis, where they had family. Ultimately, he and his mother were able to leave England, thanks to an affidavit from some distant cousins in Boston. They eventually settled in St. Louis and were reunited with Franz, who was by then a resident in medical school.

Steinberg told Dwyer his entire saga and through her was invited to view a rough cut of the film at the director’s house in Los Angeles. In November 2000 Dwyer and Steinberg attended a Royal Charity Gala Premiere screening of the film in London, with Prince Charles in attendance. It was there that Steinberg was reunited with other “kinder” featured in the film. He even met a woman who had lived in the same German village he had, two blocks away from his house.

The film played to rave reviews at the Toronto Film Festival, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial, the Boston Film Festival, the Heartland Film Festival, and in cities across the U.S. and Great Britain, before ultimately winning the 2001 Academy Award for best documentary.

For Steinberg, being involved with the film has been

an intensely emotional, often overwhelming experience but one that he

wouldn’t trade. In London, he told Dwyer, “I can’t thank

Princeton enough for bringing us together — who knew what it would

turn into!” ![]()

Kathryn Levy Feldman ’78 is a freelance writer in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

On the web:

www.intothearmsofstrangers.com