February 27, 2002: Notebook

Balancing

the bottom line

Board of Trustees approves a budget for 2002—03

PrincetonÉs endowment outperforms market

Meg Whitman seeds new residential college with gift

Whither

the U.S. economy?

If international political stability holds, the news could be good

Rothschild makes way for Trussell

Strife

between labor and management can be deadly for people who use products

made when workers are at odds with their employer, economics professor

Alan Krueger and Alexandre Mas GS found. Two years ago, Firestone and

Ford Motor Co. recalled more than 14 million tires. In congressional hearings

and lawsuits, observers wondered if there was a connection between the

faulty tires and the hostility between workers at Firestone’s Decatur,

Illinois, plant and the company between 1994 and 1996. During that time,

Firestone workers struck, and the company hired replacement workers. “We

estimate that more than 40 lives were lost as a result of the excessive

number of problem tires produced in Decatur during the labor dispute,”

Krueger and Mas wrote in a recent paper. They suggest that perhaps 250

lives were saved by the recall.

Strife

between labor and management can be deadly for people who use products

made when workers are at odds with their employer, economics professor

Alan Krueger and Alexandre Mas GS found. Two years ago, Firestone and

Ford Motor Co. recalled more than 14 million tires. In congressional hearings

and lawsuits, observers wondered if there was a connection between the

faulty tires and the hostility between workers at Firestone’s Decatur,

Illinois, plant and the company between 1994 and 1996. During that time,

Firestone workers struck, and the company hired replacement workers. “We

estimate that more than 40 lives were lost as a result of the excessive

number of problem tires produced in Decatur during the labor dispute,”

Krueger and Mas wrote in a recent paper. They suggest that perhaps 250

lives were saved by the recall.

“For some time, I have been interested in the effect of pay on worker performance,” says Krueger. While on leave as the chief economist at the Department of Labor, he adds, “I also became interested in whether replacement workers tend to produce lower-quality products.” Instead, Krueger and Mas concluded that the increase in defective tires probably stemmed from “something about the chemistry between the replacement workers and the recalled strikers, or the cumulative effect of labor strife in general.”

Krueger has taught at Princeton since 1987. Not only has he researched

issues in labor economics – he copublished a book on the minimum

wage in 1995 — he also focuses on education issues. Krueger says

there’s a connection: “Given the huge role that human capital

plays in the economy, one cannot fully understand the wealth of nations

without understanding education.”

![]()

By David Marcus ’92

Balancing

the bottom line

Board of Trustees approves a budget

for 2002—03

The economic downturn is affecting Princeton, just not as much as at other universities.

With the backdrop of a slumping national economy and the first year of what is expected to be several with budget deficits, the Board of Trustees approved a 2002—03 budget that includes an increase in undergraduate tuition and fees of 3.94 percent for next year – the largest jump in six years – and a 4.1 percent increase for graduate school tuition.

The increases were part of an $801-million operating budget adopted January 26. “It’s something we gave a lot of thought to, and at this time, in the relative scheme of things, it’s a moderate increase,” said Robert Rawson ’66, chair of the board’s executive committee.

“This year’s rate is significantly lower than the expected rates of increase of public and private institutions nationally, and is expected to allow the university to retain its competitive position relative to its peers,” said Provost Amy Gutmann in an announcement. Gutmann also noted that the average rate of increase among private institutions has been projected at 5.5 percent.

She said the financial aid budget will be increased to help students on aid cover the extra costs. Last year the university enhanced the financial aid program by, among other things, replacing loans in financial aid packages with grants.

With the percentage of students on financial aid at Princeton having increased from 41 percent in the Class of 2004 to 46.5 percent in the Class of 2005, the university had to make changes within the current year’s budget to cover about $1.5 million in aid, which led to part of a deficit for 2000—01, said Treasurer Christopher McCrudden.

Two other expenditures that were larger than expected were professor recruitment and retention, and wages for some of the university’s lowest paid em-ployees. In the fall, President Tilghman asked that an additional $1.5 million be used to raise the wages of those workers to market level ahead of schedule.

Recruitment and retention of faculty led university officials to make changes to cover an extra $1 million. Those changes involved slowing down part of the debt payment schedule on $40 million, which had been sped up last year, and using Annual Giving funds and other unrestricted gifts to cover the extra expenditures. Instead of four years, the debt, which includes renovation costs for the athletic complex, will now be paid over eight years, said McCrudden.

In all three cases, administrators said the money went toward keeping the university at the top when it comes to attracting the best students, faculty, and staff in a competitive market.

“Our financial aid program is second to none on the graduate and

the undergraduate level. We compete for the very best faculty. Princeton

has clearly stated what its priorities are and put its resources behind

those priorities,” said former Vice President for Finance and Administration

Richard Spies *72 before he left to work at Brown University in January.

“These are signs of our success. Fortunately we were able to make

necessary changes within the budget.” ![]()

By A.D.

Princeton’s endowment outperforms market

Leading

the group that oversees Princeton’s nearly $8.4 billion endowment

is Andrew Golden, president of the Princeton University Investment Company

(Princo), who also coaches his young sons’ basketball teams.

Leading

the group that oversees Princeton’s nearly $8.4 billion endowment

is Andrew Golden, president of the Princeton University Investment Company

(Princo), who also coaches his young sons’ basketball teams.

To put in perspective the performance of the university’s endowment for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2001, Golden took a page out of his coach’s playbook. “Offense may sell tickets, but defense wins the game,” he says. “We played incredibly good defense this year.”

Princo’s defensive focus led to a 2.4 percent return on Princeton’s investments, a far cry from the 35.5 percent return in fiscal year 2000. But it’s a notable result viewed against the U.S. stock market’s 15 percent drop, and considering the recession and the volatility of the markets, Golden sees the year as a success. “In many ways we can be prouder of this year,” he says. “It’s just that last year it felt a little better.”

As an example of strong defense, Princo took measures to take as many chips off the venture capital table as it could early in the 2000 calendar. If it had not, the endowment could have lost about $160 million, Golden estimates.

Taking into account the 2.4 percent return and last year’s record-breaking increase in endowment income spending, which removed $284 million, the total market value of Princeton’s endowment dropped half a percent in the last fiscal year, from $8.398 billion to $8.359 billion. The endowment is the fourth largest in the country and third largest among private schools behind Harvard and Yale, respectively.

Princeton’s modest return put it ahead of most universities in the U.S., where for the first time since 1984 the return on investments of the average university endowment lost value. Although they outpaced all the major stock market indexes, the return rate on the average college and university endowment was —3.6 percent, according to a preliminary study of 610 U.S. schools from the National Association of College and University Business Officers.

Only 165 of the 610 schools that took part in the study registered positive returns. And a look at one group that Princeton falls into – the top 25 investment pools ranked by market value of endowment assets – shows that only six had positive returns.

The return on Princeton’s endowment also outperformed the benchmark Princo uses to get a better understanding of how the endowment is performing against a weighted aggregation of the areas in which it is invested. That benchmark dropped 8.7 percent last year, Golden says.

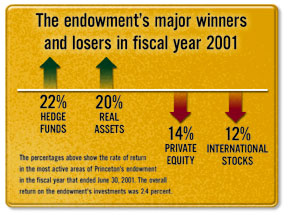

In terms of major winners and losers in fiscal year 2001, the endowment’s hedge fund investments, which make up about 25 percent of the endowment, brought in a 22 percent return. Another winner was real assets, which includes public real estate security and accounts for 4 percent of the endowment. Real assets saw an increase of 20 percent.

The major drags came from private equity investments, accounting for 15 percent of the endowment, and international stocks, which make up another 15 percent. Those areas dropped 14 percent and 12 percent, respectively.

Overall, during the past 10 years endowment investments have compounded at 16.8 percent. Golden hopes the focus remains on the long-term and the university endowment’s performance against its market benchmarks.

“Sometimes when people say focus on the long-term, it’s because

they are trying to hide something. That’s not the case here. While

our absolute return level last year is somewhat disappointing, it is essential

to understand that we beat benchmarks when the market was going down,

just as we beat benchmarks when the market was going up,” Golden

stresses. “This is symptomatic of a program that has added value

through good judgment.” ![]()

By A.D.

Meg Whitman seeds new residential college with gift

Meg Whitman ’77, president and chief executive officer of eBay, Inc., and her husband, Griffith R. Harsh IV, will give $30 million toward the construction of the new residential college to accommodate the increased enrollment at the university. The college will be named after Whitman, who also serves on the Board of Trustees.

Whitman received an M.B.A. from Harvard, and before heading the online auction company she held senior positions at Hasbro Inc., the Walt Disney Company, and Bain & Company.

A longer story will appear in our next issue. ![]()

Whither

the U.S. economy?

If international political stability

holds, the news could be good

By Alan S. Blinder ’67

Caption: Confidence in the stock market has been shaken by the collapse of Enron and by a

slowdown in mergers and acquisitions. (spencer platt/getty images)

What is the near-term outlook for the U.S. economy? It has been said that one thing you should never try to predict is the future. And it has not escaped notice that, if you reverse the word “outlook,” you get “look out!” Both are good pieces of advice for would-be forecasters.

Predicting the course of the U.S. (or any other) economy has always been a hazardous occupation; the usual uncertainties are daunting, and precision is out of the question — except by luck. But these days we have, layered on top of the usual economic uncertainties, a host of extremely unusual, indeed unprecedented, geopolitical uncertainties — all of which make forecasting next to impossible. If you want me (or anyone else) to forecast the year 2002, you must first answer a few simple questions:

• Will there be more terrorist attacks on the United States and, if so, how severe?

• Will the Middle East powder keg blow, sending oil prices skyrocketing — either because the U.S. invades Iraq or because of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

• Will India and Pakistan go to war?

Of course, none of us can answer any of these questions. So let’s think about a conditional forecast, conditioned on a benign world — that is, on a “no” answer to each of the preceding questions. What then? In that case, I’m an optimist. I believe the economy will bounce back sharply — and soon. There are four main reasons why.

First, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates aggressively throughout the year 2001. Although both markets and politicians are invariably impatient, economists have always emphasized that the Fed’s monetary policy works with a substantial time lag. According to standard statistical findings, its major impacts on the economy are not due until 2002 and into 2003.

Second, fiscal policy has also turned substantially stimulative over the past year, despite the failure of the so-called stimulus

package in Congress. The 2001 and 2002 installments of President Bush’s 10-year tax-cutting program are now in effect. And Congress has opened the checkbook for higher spending on national defense, homeland security, and a few other things. The bad news is that the budget surplus has disappeared even faster than it appeared. (That is a problem that needs to be addressed before too long.) But the good news is that lower taxes and higher government spending are now pushing the economy uphill.

Third, as everyone has noticed, oil prices have fallen very substantially since late in 2000. To most American households, falling oil prices are a godsend; they augment the amount of money available for spending on other items, just as a tax cut does. And since most American businesses are users of oil rather than producers, falling oil prices reduce costs and boost profits. (Sorry, Texas!)

Finally, one of those boring things that only economists look at: U.S. businesses have been drawing down inventories at a truly remarkable rate. Once sales turn around, many firms will need to rebuild their inventory positions, and that will provide further impetus to demand. Indeed, the current rate of inventory accumulation is so negative (about minus 1.3 percent of GDP per year) that even moving up to zero will give the economy a big boost. The arithmetic is impressive. If inventory investment moves up from minus 1.3 percent of GDP to zero within two quarters, that would add 2.6 percentage points to the annualized growth rate over that half-year (e.g., take a 2 percent growth rate up to 4.6 percent).

In my judgment, these four positive factors should provide enough fuel to blow through the negatives and power the U.S. economy upward — if the rest of the world cooperates. But that’s a big if. If events in the Middle East send oil prices soaring, or if domestic terrorism shatters confidence in the U.S. once again, all bets are off. »

Alan S. Blinder ’67 is the Gordon S. Rentschler Memorial Professor

of Economics. Vice chair of the Federal Reserve Board from 1994 to 1996,

he is codirector of the Center for Economic Policy Studies and regularly

teaches Economics 101, The National Economy. ![]()

Reading up on professors in the upper echelons of the African-American studies field these days is a little like perusing the transactions column in the local sports page — and Princeton is definitely in the game.

On January 26 the Board of Trustees appointed philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah as the Laurance S. Rockefeller University Professor of Philosophy and the University Center for Human Values. Currently a professor at Harvard, Appiah is considered one of the top African-American studies scholars in the country.

President Tilghman said Appiah’s addition “brings even greater distinction to our philosophy department, to our Center for Human Values, and to our distinguished and growing work in African-American studies.” University officials have been talking about expanding the African-American program into a full department that would grant degrees.

Appiah, a Cambridge University alumnus, leaves Harvard at a time when its Afro-American department is making national headlines. Comments from Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers on the work of professors within the department led to criticism and to reports that scholars Henry Louis Gates, Jr., department chair and a close friend of Appiah, and Cornel West *80 were heading to Princeton. West left Princeton for Harvard in 1994. Gates has said he is waiting until summer to make his decision on leaving Harvard.

Provost Amy Gutmann has been credited with playing a critical role in luring Appiah to the campus. Gutmann coauthored an award-winning book, Color Conscious: The Political Morality of Race, with Appiah in the 1990s.

“It was a pleasure to collaborate (with him) and I continue to learn from Professor Appiah’s writings and our far-ranging conversations, as do so many other colleagues here at Princeton and around the world,” said Gutmann. “He is widely regarded as the world’s leading intellectual on the relationship of identity, culture, freedom, patriotism, and cosmopolitanism.”

At the same meeting, the board also approved the hiring of James Van

Loan Haxby as a professor of psychology. ![]()

By A.D.

Rothschild makes way for Trussell

Michael Rothschild, dean of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, moved his resignation to February 1, a semester earlier than planned, after two disagreements with President Tilghman.

Rothschild initially announced his resignation on October 1 and expressed his intention to remain dean until June. In a short letter to Tilghman on January 7, Rothschild indicated that he was resigning early because her administration had made two “important decisions about Woodrow Wilson School resources and [Center for International Studies] policies without consulting the dean or the director.” He will continue to teach.

In one case, Rothschild wanted to suspend the CIS fellowship program for visiting scholars for a year in order to bring in more senior faculty, according to Professor Richard Ullman. Though former President Shapiro supported the plan, Ullman and other CIS faculty believed that CIS policies should be reformed while leaving the fellowship program intact. After Ullman expressed his opposition to the plan in a memo to the president, Tilghman overrode Rothschild’s recommendation and continued the program. Rothschild and Tilghman would not comment on the other disagreement mentioned in the letter.

James Trussell, associate dean of the Wilson School, has been named

acting dean, and Ullman has been appointed acting director of the CIS.

![]()

By Nathan Kitchens ’02

Louis A. Pyle, Jr. ’41, a longtime university physician, died January 14 at his home in Princeton. He was 81.

Pyle came to the university in 1971 and was in charge of clinical services as well as sexuality education, counseling, and health. He led the establishment of specific health services for women after the university became coeducational. In 1976, Pyle became director of athletic medicine. The following year, he became the director of Health Services and an officer of the university, a role in which he modernized the university’s delivery of campus health services, expanded the integration of the health services with the area’s larger medical community, and continued the advancement of clinical and athletic medicine. His tenure as director was so successful that he was able to twice extend his term beyond the customary retirement age.

Commenting on Pyle’s service, former Princeton provost and Harvard University president Neil Rudenstine ’56 said, “It was difficult to imagine how anyone could oversee a college health service with such humane vision and sensibility on the one hand and marvelous competence on the other. He did more than practice medicine for students, he gave them a sense of what a physician in the broadest sense could be and should be. That was a great gift to Princeton.”

Robert George, the McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence and professor of politics, was named by President Bush to the Council on Bioethics, an 18-member group that includes doctors, scholars, scientists, and a journalist. The council, which was established last summer as part of Bush’s decision that limits federal financing for human embryonic stem-cell research, will advise the president on ethical issues, such as stem-cell research and cloning. George previously served on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights and is a former judicial fellow at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Peter McDonough, a member of Princeton’s legal staff for 12 years, has been promoted to lead that office as general counsel. He succeeds Howard Ende, who will leave the university later this year to become president of the Mpala Wildlife Foundation in Kenya.

Two Princeton graduate alumni received awards last December. Brad Gregory

*96, who earned a Ph.D. in history, was awarded the Gustave O. Arldt Award

“for a young scholar teaching in the humanities at an American university

who has earned a doctorate within the last seven years and who has published

a book deemed to be of outstanding scholarly significance.” His book

is titled Salvation at Stake: Christian Martyrdom in Early Modern Europe

(Harvard Historical Studies). The Council of Graduate Schools bestowed

a Distinguished Dissertation Award on ecology and evolutionary biologist

Robin Knight *01, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on “The Origin

and Evolution of the Genetic Code: Statistical and Experimental Investigations.”

![]()