July 3, 2002: Features

Essays:

Reflections:

On 25 years of Reunions

By James Barron ’77

Against

the current: How one woman found strength, and comfort,

by breaking down barriers

By Jodi Picoult ’87

Reunions 2002

Photographs by Ricardo Barros and Frank Wojciechowski

As the Class of 1977 wound its way along the 2002 P-rade path in front of Nassau Hall, the lengthy procession raised the question, “Are they circling back around?”

What seemed like an endless stream of proud ’77ers decked out in mod orange, black, and white bowling shirts got this year’s P-rade started with a bang, and the energy never let up, even after the final locomotive for President Tilghman at the reviewing stand.

The pounding sun might make some classes reconsider black as a primary beer jacket color, but nothing else diminished the merriment that came with the more than 17,000 Princetonians and relatives who took over the campus during Reunions 2002 weekend, May 30—June 2.

Between meeting old friends, making new ones, and, for some, chasing after their kids as pajama parties and other tent parties carried on late into the night, many alumni were caught up in the whirlwind that is Princeton Reunions. “There’s so much, it’s just a great time,” said Anthony Santullo ’82, who led his class in the P-rade behind the wheel of a Model T.

But it wasn’t all P-rading, beer drinking, and fireworks (was it?). With the formidable Class of 1952 leading the way, dozens of faculty and alumni forums and discussions injected intellectual stimulation into the weekend. The 50th Reunion Roundtable, called Frontiers of Knowledge and held in Alexander Hall, covered topics ranging from literary studies and the urbanization of the world population to biology and European affairs. Other subjects of debate included the place of athletics in the Ivy League, the role of the artist at Princeton, and a question-and-answer session with President Tilghman that covered a broad range of topics, including alcohol on campus, her tenure, and legacies. (See Notebook, page 10.)

There were a few reunion firsts this year as well. The Whig-Clio Alumni Association held its first cocktail reception, and the Class of 2000 put on “Stagefright,” an open-mike night at Café Vivian in the Frist Campus Center that allowed alumni the opportunity to put on their own show.

While Sunday closed with brunches and farewells, next year’s major

reunion classes had already started planning for Reunions 2003 and another

orange-and-black attack to take over Princeton. At least there are 52

weeks to catch up on sleep and get those locomotives roaring again. ![]()

By A.D.

|

Sam DeCou ’52 catches a ride and gives a cheer during the P-rade. |

The Class of 1947 showed no signs of aging. |

Kristin Larson, left in orange vest, and Jennifer Jones Boyd, center, celebrate 1997’s survival of five post-Princeton years. |

|

“I can’t believe it’s been 25 years”: The Class of 1977 on the steps of Blair Arch |

Rose Frye West ’77 under the big top |

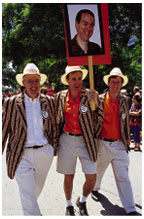

’77’s Fred Rich, Rick Hamlin, John Speers |

|

1987 threw one big slumber party and opened a few eyes with its striped jammies. |

Andy Russell ’82 gives his son Alex a lift along the P-rade route. |

Ron White *72, outgoing Graduate School dean John Wilson, and Ruth Wilson P-rading |

|

Silver Cane winner Leonard Ernst ’25 |

Alison and Henry Penick ’72 |

Lew Van Dusen ’32 made it for his 70th. |

|

Bob Thomas ’42, left, and Buzz Seibels ’42 |

Giving a ’57 cheer are from left, Irv Flinn, Wright Elliott, and Hodding Carter. |

Bob Stuart ’37, left, steps lively next to classmate Penn Kimball. |

|

From left, 1992’s Claire Kaplan, Mary Kelleher, Rob Huckman, and Janine Pisani McGuire |

Mike Hartman ’62, Michael McConihe ’62, and Tom Dunn ’62 are sporty in stripes. |

Celebrating ties that bind are 1967 classmates Dick Fiss, left, John Bender, and Buz Code. |

|

Bob Cowen ’52, Paul Busse ’42, Rudy Lehnert ’52, Mal Cleland ’52, and Frank Harvey ’52 |

Lucius Wilmerding ’27 |

From left, Bill Highberger ’72, Wally Good ’72, and Phil Shinn ’72 |

|

The younger set showed plenty of spirit at Mom and Dad’s 20th. |

On 25 years of Reunions

By James Barron ’77

I am staring at myself in one of those three-way mirrors that they have in clothing stores. It’s no funhouse mirror. Thankfully, it’s not making me look wide in places that I’m not and thin in places that I’m not. Certainly not: This is a serious store, I am a serious customer, and it’s April. I am trying on a khaki-green summer weight suit — the third that I have owned.

Buying a khaki-green summer weight suit has turned into my personal pre-Reunions ritual. I bought the first one for my fifth in 1982, when I wanted to look like I belonged.

But that suit is nowhere to be seen in my Technicolor, wide-screen memories of our fifth. What comes to mind is the aftermath of a newspaper story I wrote about getting rained on during the P-rade — something about following a tiger-in-a-cage float in a downpour. This brought an angry letter to the editor from an alum in Cincinnati. He was adamant: It had not rained.

It took a couple of calls, but soon I established that President Bowen had been drenched in the you-know-what, too. Maybe our letter-writer had spent the weekend on a sunny beach with a sunny someone. Back home, people wondered how he had gotten a George Hamilton tan when they had been reading about soggy, sorry Princeton.

Fast-forward 10 years, to my 15th and my second khaki-green suit. (That was the year that the Class of 1977 deployed a P-rade float that ripped some of the ivy off East Pyne. Don’t ask.) Fast-forward another 10 years, and you won’t be surprised to hear that khaki-green summer weight suit No. 3 has been hanging in my closet for a couple of months.

Only after I left the store did the realization hit me: I won’t need the suit this time. This is the year we get blazers.

I remember watching the 25th reunion class march by when I was a senior and wondering what it would be like to be as old as those guys. No doubt this year’s about-to-be-alums said the same thing as we toddled by. If only they knew the whole story. I hear that about a dozen of my classmates scheduled pre-Reunions plastic surgery — a nip here, a tuck there, a lift somewhere else. They did not just go back, they found a way to go back to what they looked like in the 1970s, or maybe better. And all I did is buy a suit that looks exactly like the last two.

Soon there will be a new residential college, named for one of my classmates. The M. Taylor Pyne of a century later is a woman.

How I wish I could tell the first occupants of Whitman College that their lives will be as good as mine has been. We were too young for Vietnam, and as adults, we sailed through placid, prosperous times, largely insulated from the kinds of global unrest that we had studied at Princeton.

And then, just as our 25th reunion year was dawning, we were hit by attacks on the quintessential symbols of American wealth and power. Like the day on which John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963 or the day on which Pearl Harbor was bombed in 1941, September 11 instantly became one of those days that divides things into “before” and “after” — the first such big-history day in our adult lifetimes. For the first time, I had no sense of what the future might bring.

I wrote my senior thesis on the uses and abuses of presidential power — a ripped-from-the-headlines topic, but remember, we were rising sophomores when Richard Nixon resigned. The very notion of presidential power implies that there will be a distinctly American future, just as there was a distinctly American coloration to so much of the 20th century.

Now it’s the 21st century, and our 25th reunion has come and gone

in an era of flag-waving anxiety, when it’s almost fashionable to

echo the homey patriotism of a Norman Rockwell painting. How I find myself

wishing for the cool, forward-looking confidence that Eric Goldman imparted

in History 377 (Modern America). How I wish the Wilsonian shibboleth could

be changed to “Princeton in the world’s service.” How I

wish I believed that would make the difference. ![]()

Class secretary James Barron ’77 writes the “Boldface Names” column for the New York Times.

How one woman found strength, and comfort, by breaking down barriers

By Jodi Picoult ’87

s a 5' 2" freshman woman whose athletic abilities were limited to simultaneously walking and chewing gum, I hadn’t had any reason to explore Dillon Gym until the Monday I decided to join the crew team.

The Rowing Office was located at the end of an L; a small room crammed with three desks, stacks of paper, and a wet dog. A placard announced the names of the coaches: Larry Gluckman, Men’s Heavyweight Crew; Gary Kilpatrick, Men’s Lightweight Crew; Curtis Jordan, Women’s Crew. I peered inside. One man was on the phone, another was sitting at one of the desks. “Can I help you?” he asked.

I learned later this was Curtis. “Actually, I wanted to help you,” I said, walking inside. “I wonder if you need a manager.”

“Got one,” he told me. “So do the lightweights. The only team that doesn’t have a manager is the heavyweights, and — ” Here he glanced up. “And you’re a woman.”

Well, yes, I’d noticed that. Before I could answer, a voice behind me responded – the man who had been on the phone. “What do you know about rowing?” Larry Gluckman asked.

The first time I’d ever seen a crew shell was a few weeks before, when the team did Freshman Week recruiting in front of Dillon. Other than that, well, I’d watched the Head of the Charles in Boston the previous weekend and been taken by the sport’s beauty: a ballet on water; a rainbow of oars.

But my real reason for going to Dillon that Monday had nothing to do with the sport. After three weeks as a freshman, I was homesick. I didn’t feel like I fit in at this university, and more than anything, I wanted a group to call my own. The question wasn’t Why crew? It was Why not?

“What do you know about rowing?” Larry repeated.

It was nice to watch. And I was organized, efficient, and friendly. Surely those qualities were all you needed to manage a team; the sports knowledge could seep in by osmosis.

I had no idea that, at that time, women did not generally become part of men’s teams at Princeton, or vice versa, not even in the capacity of a manager. I had no idea that old habits at Princeton die hard, and that the alumni would balk at the very sight of me; that the rowers themselves would complain. Yet in spite of all this, Larry said yes, they could use a manager for the heavyweights. He told me to come to the informational meeting at Alexander Hall the following week, where he would introduce me to the team.

Years later, he admitted he never expected me to show up.

Not long after that meeting, I arrived at the boathouse for practice, and got my first taste of what it is like to break boundaries at Princeton. The heavyweights – my own team – largely ignored me. The women rowers glared at me. I stood beside Larry as he barked practice orders to the coxswains, only to be told that I was going to be coxing as well. My stroke — the guy facing me as I sat in the boat, who set the pace for the rest of the rowers — was Tim van Leer, hand-picked for this little exercise by Larry because he was least likely to toss me into the lake in utter frustration.

In my four years of tenure as the first woman on the men’s heavyweight crew team, I coxed during seat racing and scattered practices. I painted oars with our boatwright, Frank Bozarth; I staggered to 6 a.m. boathouse calls; I booked travel arrangements. I learned how to swap rowers mid-lake. I held sterns steady at the start on the Schuylkill, waiting for the call: Sit Ready, Ready All, Row. I charmed the alumni, who stopped averting their eyes from me and instead began to ask me for race stats. I spent winters with a stopwatch in my hand, monitoring the four stations of an Hour of Power. I rowed through Hurricane Gloria; I spent spring breaks on the water in Tampa. I got used to walking into the men’s locker room without blushing. I spent hours in the driving rain on a launch on Lake Carnegie, a mascot with curly hair and an oversized Helly-Hansen jacket, trying to videotape practices for training. I became one of them.

Groucho Marx once said, “I don’t care to belong to a club that accepts people like me as members.” Conversely, we all want to be part of the group that excludes us. It is the reason that Ivy League schools are elite; it’s the impetus that propels people toward selective eating clubs – when you have to work to be accepted, the welcome is that much sweeter. Maybe that was my motivation for coming back to the boathouse day after day – to make my presence known subtly and firmly, and to win over a team that was inclined to overlook me. Amazingly, it worked. After a few months, there wasn’t a single man on the heavyweight team who questioned my right to be there. In fact, when I was a senior, and the coach asked me to find my own replacement, he fully expected it to be another woman.

My dogged pursuit to be listed on an all-male team roster built skills that I have called upon again and again. If I hadn’t broken down this brick wall in college, maybe I would have quit early on in the publishing game when I got a few rejections, rather than persevering to the point where my ninth novel is being published. Having the backing of a coach like Larry Gluckman, a man who became my surrogate father for four years, taught me how a mentor can make you into a stronger person than you ever imagined you might be. And the life metaphors inherent in the sport of rowing cannot be discounted either: working hard, pulling your weight, and relying on the unified efforts of others around you are the surest ways to cross a distant finish line.

In high school, I never would have guessed that I’d join a crew

team, much less one made up of men. In college, I never would have believed

my actions might pave the way for today’s female coxswains on the

Princeton men’s crews. And even when I graduated, I’d never

have imagined that one day Larry Gluckman would make a toast at my wedding

to Tim van Leer ’86, former captain of the heavyweight team and stroke

of the first boat I set foot in, a man I still trust to get me safely

back to any shore. ![]()

Jodi Picoult ’87 is the author of nine novels, including Mercy, Plain Truth, The Pact, and most recently, Perfect Match.