April 9, 2003: Notebook

SUBJECT

MATTERS

The class: GEO 210 Earthquakes, Volcanoes, and Other Hazards

Top

of the world

Library celebrates first Mt. Everest climb with exhibition

The class: GEO 210 Earthquakes, Volcanoes, and Other Hazards

While most people just talk about the weather, students enrolled in Earthquakes, Volcanoes, and Other Hazards learn the nitty-gritty science behind extreme weather and natural disasters. They also examine issues affecting government and industry: Should the U.S. send aid to countries hit by weather catastrophes? Should people be allowed to live in areas known to be affected by extreme weather, earthquakes, or volcanoes?

These are two of the questions professor Guust Nolet and associate professor Allan Rubin address with the more than 100 students who sign up for the class each spring. “Geosciences is not a discipline by itself,” says Nolet. “It is rather special in that it attacks complicated real-life problems. It uses the classical disciplines of chemistry, physics, and biology to study the world.”

The professors do not expect any special math or science background for the class, so many A.B. students take “Shake and Bake,” as it is known, to fulfill a lab requirement. Students learn to use geographical information systems, which allow users to access a wealth of information, from topography to weather to demographics, about a particular location. They learn to combine census tracts with scientific data to apply geophysics to risk assessment.

The class also looks at the economic impact of weather — the destruction hail wreaks on crops and the billions of dollars worth of damage done by hurricanes.

Technology has made a huge difference to geophysics. “Before satellite

photography, all we knew about developing weather came through messages

from ships and weather balloons, says Nolet. ![]()

By A.D.

Reading list: D. Abbot, Natural Hazards

Top

of the world

Library celebrates first

Mt. Everest climb with exhibition and conference

By Kathryn Levy Feldman ’78

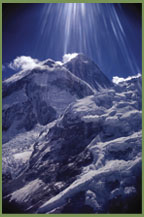

Photos: James Ramsey Ullman ’29, right, with Tenzing Norgay in 1963 in the Himalayas. (department of rare books and special collections, princeton university) The world’s highest peak was named for Sir George Everest, surveyor general of India from 1830-43. (courtesy of ed webster)

Fifty years ago May 29, Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached the summit of the world’s highest peak, Mt. Everest, at 29,035 feet.

Forty years ago, on May 1, 1963, the first American, James Whitaker, made it to the top, and a few weeks later the Americans William Unsoeld and Thomas Hornbein ascended the peak via the West Ridge, another first.

On Saturday, April 12, the Friends of the Princeton University Library host a conference to commemorate the first ascent, called “On Top of the World: An Everest Anniversary Conference.” (The conference is free and open to the public. For information, 609-258-3174.)

Princeton’s

connection to both anniversaries is the late James Ramsey Ullman ’29,

an experienced climber and successful adventure travel writer of nine

nonfiction works, 10 novels, and 12 plays. Besides writing the official

record of the 1963 American expedition, Americans on Everest (1964), he

ghostwrote Tiger of the Snows (1955), Tenzing Norgay’s autobiography.

Princeton’s

connection to both anniversaries is the late James Ramsey Ullman ’29,

an experienced climber and successful adventure travel writer of nine

nonfiction works, 10 novels, and 12 plays. Besides writing the official

record of the 1963 American expedition, Americans on Everest (1964), he

ghostwrote Tiger of the Snows (1955), Tenzing Norgay’s autobiography.

The conference features four speakers including Hornbein and Ed Webster, another Everest climber. Also planned is a panel discussion, “The Changing Face of Mt. Everest: The Politics of Mountaineering,” and an exhibition of manuscripts, photos, and memorabilia, on loan from the participants or culled from Ullman’s papers, which are part of the library’s Rare Books and Special Collections holdings.

Why climb Mt. Everest? According to panelist Maurice Isserman, professor of history at Hamilton College and coauthor of a work in progress on the history of Himalayan mountaineering, the answer is more complex than George Mallory’s “Because it is there.”

“Everest was always bound up with issues of national prestige, in the region and globally,” Isserman says. “When Hillary and Tenzing got to the top in 1953 in time for the news to reach London, where Queen Elizabeth’s coronation ceremonies were about to start, it was celebrated as a symbol of the beginning of a new Elizabethan Age. Other countries would have loved to have been there first.”

Which is why, Isserman says, in an effort to gain the considerable resources necessary for a full-scale siege of the mountain, Norman G. Dyhrenfurth, the leader of the 1963 expedition, “sold it to the public in general and the Kennedy administration in particular as a means to further American aims in the Cold War, to prove that the nation was not growing soft and decadent, to impress South Asian publics, etc.”

Things have changed since the 1963 expedition, Isserman observes. “The question of national prestige is only occasionally invoked by climbers of Mt. Everest,” he says. “More and more, climbing Everest has become a matter of commercial enterprise and conspicuous consumption with the rise of professional guiding services.” Last spring approximately 100 climbers stood atop Everest on the same day. That was a far cry from the “mass” Ullman wrote about in his cover story for Life magazine in September 1963, entitled “Mass Conquest of Mighty Everest,” which consisted of six climbers (five Americans and a Sherpa). “That tells us a great deal about how Everest climbing has been transformed over the decades since the initial British and American triumphs,” Isserman says.

The lure of the uncharted was a significant aspect of the perilous ascent of the West Ridge for Hornbein, a physician and professor emeritus at the University of Washington. He theorizes that the human need for risk has led to many of the changes that have taken place in subsequent expeditions, both in the methods used and in the people who have made the climb. “The need by mountaineers for uncertainty has made style an important ingredient; skiers and snowboarders are descending from its summit, and those less experienced are being helped to the top by professional guides,” Hornbein says. “I feel fortunate to have been born when I was, to have climbed on Everest when it could still be a far-out adventure.”

For Ullman, who went as far as Kathmandu with the 1963 team, being included

in the expedition was the fulfillment of a lifetime ambition. “It

meant an enormous amount to me to be part of the American Everest venture,

no matter in how rear-echelon a capacity,” Ullman wrote. “Everest

had been a great dream of my life since I was a boy.” ![]()

Kathryn Levy Feldman ’78 is a freelance writer in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania.

War

protesters gather

War

protesters gather

Photo: frank wojciechowski

Marchers with masks and dolls hold a symbolic funeral procession to

protest the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq. The Princeton Peace Network demonstration,

which took place March 20 during spring break, drew about 125 people,

including local residents and Princeton Theological Seminary students.

The rally began on the steps of the Woodrow Wilson School and ended downtown,

where three students were arrested for blocking Nassau Street traffic.

Other war-related activities were to include a March 24 panel discussion

at the W.W.S., and speakers and pamphleting organized by the Princeton

Committee Against Terrorism, a student group that supports the invasion.

![]()

Colonial Club president Benjamin Handzo ’04 was charged with serving alcohol to an underage student and maintaining a nuisance after a 20-year-old female was found drunk and incoherent in front of the club March 8, Princeton Borough police said.

The student was treated at Princeton Medical Center and released. Handzo,

21, was the sixth club officer to face charges for serving alcohol to

minors since February 4. An undercover police operation at the eating

clubs began in November. ![]()

Five Princeton faculty members have received Alfred P. Sloan Foundation fellowships. The $40,000 grants recognize young scientists and scholars. The recipients are associate professor Steven Gubser, physics; and assistant professors Moses Charikar, computer science; Wee Teck Gan, mathematics; Han Hong, economics; and Christopher Tully, physics.

The Chronicle of Higher Education has announced a David W. Miller [’89]

Award for Student Journalists. Miller, a former PAW staff writer, was

a reporter for the Chronicle when he was killed by a drunk driver last

year. The annual award, a $1,000 prize and a certificate, will be given

to a candidate whose work appeared in a campus publication and reports

“evenhandedly on a topic of intellectual interest.”

![]()

www.princeton.edu/webmedia/lectures

Lawrence Lessig, Stanford Law School professor and founder of the law school’s Center for Internet and Society: “The Creative Commons” — how societies depend upon independent, well-regulated social criticism.

Vincent Poor, professor of electrical engineering,: “Anytime, Anywhere: The Recent Revolution in Wireless Communications”