September 10, 2003: Features

|

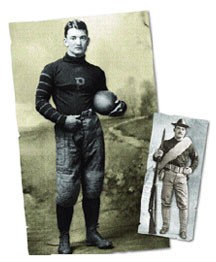

Left, John Prentiss Poe Jr. 1895 as a Princeton football hero, and right as Corporal Poe in the U.S. Army. (Princeton University Archives/Anne Poe Pierpont Lehr/photo enhancement: Steven Veach)

The Poe brothers, all members of the varsity football teams, from left, Arthur Poe 1900, S. Johnson Poe 1884, Neilson Poe 1897, Edgar Allan Poe 1891, Gresham H. Poe 1902, John P. Poe Jr 1895. (Princeton University Archives)

Johnny Poe in his early 30s, when he was working out West in a mining town, with unidentified friend. (Anne Poe Pierpont Lehr) |

A Princeton hero’s search for meaning

By Mark F. Bernstein ’83

It was many and many a year ago, in a kingdom by the sea (the sea in this case being the Raritan Canal) that a young man lived whom you might know – or would have known had you been a reader of almost any Eastern newspaper in those days. His name was John Prentiss Poe Jr. 1895, though he was “Johnny” to everyone who followed his exploits on the gridiron or his search for adventure in distant fields. Though he was a first cousin twice removed of Edgar Allan Poe, Johnny might better have stepped out of the pages of Kipling.

Johnny Poe was a mercenary, a soldier of fortune, a seeker of death. The press, which eagerly reported his wanderings and continued to lionize him long after his death, portrayed him as a jolly vagabond. It was an image Johnny did much to encourage, in jaunty letters to friends and classmates that provided most of the journalistic fodder. But it was a hard act to live up to, for a soldier of fortune is also Fortune’s victim. Johnny’s private letters to his family, more than 200 of them, which have sat for decades in his family’s possession, cast the happy wanderer in a much more lonely light, striving for glory that always would be just beyond his grasp.

One of six football-playing brothers to attend Princeton in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was Johnny’s good fortune to come along at a time when the romantic reputation of what would become the Ivy League was being forged, along with its athletic reputation. Good players became celebrities while those with a hint of tragedy about them, like Johnny or Hobey Baker ’14, became legends.

By the time Johnny arrived at Princeton in 1891, his two older brothers had established the family’s name in athletics. Samuel Johnson Poe 1884 led the Tigers to their first national lacrosse championship. Edgar Allan Poe 1891, named after their famous cousin, was quarterback of the first All-America football team. Three younger brothers – Arthur, Neilson (Net), and Gresham – also would play for the Tigers, Arthur achieving the family’s greatest athletic fame with a celebrated field goal that beat Yale for the national title in 1899.

The fame of Johnny’s older brothers, no doubt, had something to do with why the freshmen elected him their class president, but there was also his own disarming modesty. “Fellows, I am proud of the honor you have bestowed upon me,” a classmate recalled him saying at their first assembly in the chapel. “My face can’t be ruined much, so I’ll go into all the battles with you head first.” In a storied snowball fight that winter, he led the class to victory over the sophomores in battle so bloody that the faculty outlawed all future contests.

Johnny moved straight to the football varsity and, although he stood only five-foot-five and weighed 143 pounds, tied for third on the team in touchdowns scored. Even so, in an age when Princeton football received as much press attention as any professional team does today, that was enough to make his name familiar. But he flunked out of school the following spring, a failure to apply himself that presaged many future disappointments. The morning he left for home, his entire class escorted him to the train station to say good-bye.

As he had promised, Johnny returned to Princeton in the fall of 1892 and did even better on the gridiron. “As a half-back Johnny Poe has few equals,” Harper’s Weekly enthused. A perfectionist in things he cared about, he would spend hours in his room after practice pitching a football into a pile of sofa pillows until he got it right. He did not apply himself to studying with the same kind of dedication, and was expelled again before the school year was out, this time permanently.

Adrift, Johnny cast about for something to do with his life: coaching football, working for a steamboat operator, selling real estate and coal. Like many of his generation, he had been raised on romance. But as he confessed to a friend during this time, “This scramble for the almighty dollar does not appeal to me, as I am so utterly rotten in the scramble.”

Johnny Poe wanted to be a soldier. For anyone. Anywhere. Surely, he once wrote to a Princeton classmate called Bos, “there must be some such man who, disgusted with the awful sameness of things, would enjoy observing how the grandest game on earth is conducted in China, Arabia, Central America, Formosa, Borneo, or the Congo.”

Johnny’s father had not marched off to battle. Like many well-to-do men of his generation, John Prentiss Poe Sr. 1854 had paid a substitute to fight in his place, a derogation from the code of honor that must have diminished him in the eyes of his middle son. Poe Sr. was famous in his circle – attorney general of Maryland, founder of the state law school, and a longtime Democratic political leader – but the relationships between famous men and their sons are often strained, and one senses that this was true of the Poes. “Why is it that all the children love you so much more than me?” he once wrote his wife. “Will I ever understand the reason?”

Most of the gallantry in the family came from their mother’s side, and Johnny was his mother’s son. Anne Johnson Hough was the daughter of Maryland slaveholders and rabid secessionists, a family so suspect by Union authorities that her Baltimore wedding in 1864 was held under armed guard. Her nephew, Bradley Johnson, was a Confederate general. Gresham Hough, her brother and Johnny’s uncle, rode with Mosby’s dashing raiders.

With that to aspire to, and perhaps his father’s contrary example to expunge, Johnny joined the Maryland National Guard and was called to active duty soon after the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898. His regiment made it as far as Tampa, where the men waited for a transport to take them to Cuba. The Rough Riders, which were filled with ex-Ivy League athletes, were there as well, but Theodore Roosevelt was able to find a ship for his men while Johnny’s commander did not, and so his unit spent the rest of the war in Huntsville, Alabama. Still, he wrote his class secretary, “I am having a corking fine time and don’t care how long this unpleasantness between the two countries keeps up. Just think of my getting $21.60 a month for a little bit of drilling, and the rest of the time lying under the trees reading the newspapers as we used to do at Princeton.”

Later that year, Johnny jumped at the chance to fight guerillas in the Philippines, passing up a chance at a commission had he stayed home. This time he made it to the front, but saw no action. Bored and humiliated, he asked his father to buy his way out of the army.

Returning home to Baltimore, Johnny worked for a few months as a surveyor before escaping to New Mexico to be a cowboy. But that did not work out either, and he returned East again in the fall of 1902, where he was still so popular with his old college mates that when Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated as Princeton’s president, Johnny was asked to serve as a marshal for the installation ceremony, a remarkable honor for a man who never had come close to graduating. (He declined.) Falling back on the only other work he knew, Johnny served as an assistant football coach that season and again in 1903, when the Tigers won the national championship, giving them a motto – “If you won’t be beat, you can’t be beat” – that would be Princeton’s rallying cry for years afterward.

Johnny might have made a good coach, but when the governor of Kentucky called out the militia in 1904 to suppress the “Black Patch War” by small tobacco farmers against the cigarette companies, he dropped football and volunteered. When Roosevelt, now president, sent an American force to Panama a few months later, Johnny dropped Kentucky and volunteered for that, too. Mindful of his previous disappointments, he sought a guarantee of action before he enlisted. “If I were to go there, to Panama, and not see any service,” he wrote the Marine Corps commandant, “I would feel that if I were to go to Hades for the warmth the fires would be at least banked, if not altogether extinguished, owing to furnaces being repaired.” That brash letter so impressed the commandant that he not only got Johnny the commission he wanted, but swore him into the service personally. Still, within weeks of landing in Panama, Johnny asked to be reduced in rank. “Nobody expects anything of a second lieutenant,” he explained to the colonel in charge of his regiment, in a story reprinted with amusement in the Marine Corps Gazette. “They do of a sergeant.” Instead, he was put in charge of the mules that pulled the unit’s heavy guns.

By the fall of 1905 he was out in the hamlet of Goldfield, Nevada, working as a watchman in a gold mine and writing to inquire if the Imperial Japanese Army would let him join the Russo-Japanese War. To his friends, he professed to be delighted with his salary of seven dollars a week. But to his family, he confessed that he hated mining and preferred the short dinner time in camp because it left him little time in which to make conversation with the other men.

Johnny was a great storyteller, and his frequent letters to friends and classmates often made their way into the New York Times, the Baltimore papers, or at least PAW. In one article, his classmate Edwin M. Norris related a story Johnny had told him of organizing a prospecting expedition across Death Valley in search of an abandoned gold mine. When they finally found the “gold mine,” it turned out to be only three empty wooden chests. On another trip, a fellow prospector chastised Johnny for carrying a silver soapbox, a giveaway of his pampered upbringing. “The next time I go,” he jauntily vowed in a letter, “I shall pull two-thirds of the bristles of the toothbrush out and break the comb in half and wipe my face on the horses’ manes.”

Still, an undercurrent of melancholy ran deep. By early 1907, he confessed, “I am tired of mining and only hanging around here and longing for something worthwhile to happen someplace in the world.” A few months later, Johnny abruptly left Nevada when he read that war had broken out between Nicaragua and Honduras. “I have made such a botch of my life and probably will continue to do so, that I can’t see where I quit so much the [worse] should I die in Nicaragua,” he wrote his brother Net before shipping off. “There is no occasion for mother to be worried. There is no fighting in Nicaragua but as soldiering is about the one thing I still can take a little bit of interest in, I think I might as well follow it up till the interest in that dies, too.”

Johnny embarked with the intention of joining the Nicaraguan army, but when his steamer was held up in Honduras for several days, he got off and joined the Honduran army instead. “No matter where or on what side,” he once joked, “they are both usually wrong, so it doesn’t make much difference which one chooses.” “El Capitan Poey,” as the Hondurans called him, was at last in the thick of a fight, commanding an artillery piece while earning, he proudly reported to another classmate, Wilfred Hager, two pesos a day – about 85 cents.

His mother once observed with exasperation that Johnny’s “only idea of life seems to be traveling around gathering experiences to narrate to Princeton audiences.” One of his best came when the Nicaraguans captured him as a spy and threatened to stand him before a firing squad.

“I was wondering what to say to get into the ‘noble saying before dying’ class,” he wrote Hager in another letter. “While I remembered Nathan Hale [and] General Wolfe . . . none of these seemed to do justice to the occasion, and I fear I should have been compelled to fall back on such trite and worn out sayings as this: ‘Fire, you mustard-colored, black and tan – and be damned to you.’ I know I should have been mortified to death at having this rather bourgeois remark on my tombstone, but what could I say with no whiskey to give me some poetic thought as ‘I trust you will never have to shoot a more innocent man.’ Hell! Hell! Hell!”

Instead, after two days of rough questioning, the Nicaraguans released him and told him he had 48 hours to leave the country. In one of those impossible twists of fate that seemed to follow him, he was rescued by a visiting American gunboat, the U.S.S. Princeton.

Johnny made it back to campus in time for Reunions that June, where he stayed up late under the tents on warm June evenings and awed his lawyer and broker classmates with tales of distant fields. But then there was nothing to do but return to the mines and oil wells, though the press reported that he had been found dead in the mountains of Mexico. “Lord how I hate this work,” he moaned in a letter to his mother. Most nights he spent reading in his barracks, alone with his dreams.

While digging a ditch one day, Johnny decided to contact the Nevada governor about joining the state police. He was commissioned as a special deputy and sent off to infiltrate a gang of cattle rustlers. Disguising himself as a prospector, Johnny spent weeks gaining their trust before personally leading the posse that swooped in to arrest them. A few years later, he happily interrupted his mining career again for a two-year stint in the Klondike, joining a government team that surveyed the boundary with Canada.

At the age of 41, Johnny Poe was a veteran of five wars, but the soldier of fortune was growing older. World War I gave him a last chance at glory. Within days of the outbreak of fighting in 1914, Johnny went to Canada and enlisted in the British army. He was on a ship bound for Europe before the end of the month, selling his cufflinks to buy some Shakespeare and the Book of Common Prayer to read on the voyage. “Certainly dry reading,” he wrote his mother.

Finding himself stuck in the Royal Garrison Artillery, lobbing shells over a hillside, he asked to be transferred to the infantry and joined the Black Watch, the ancient Scottish regiment. Here, one suspects, was what he had always been looking for: men marching into battle in kilts, their standards waving and the bagpipes playing “Highland Laddie.”

More than 130 of his classmates, who still adored him, sent postcards to Johnny in France to wish him well. But there was little room in the trenches for the romantic, gallant martial ideal on which they had been raised. Johnny Poe was killed in action on September 25, 1915, at the Battle of Loos. In the hands of the mythmakers, one account of his death said that he carried four or five men to safety after being hit. Another said that as he started his last charge across no-man’s-land, he began calling out his old football signals.

The truth, though more prosaic, was no less touching. According to the official report of the battle, Johnny was carrying several boxes of shells when he was shot in the stomach. “Never mind me,” he told his comrades, “go ahead with the boxes.” When they returned a short while later, they found him dead and buried him near a place called Lone Tree. Scores of people have searched, but his grave has never been found.

Johnny’s name was inscribed on the Black Watch roll of honor at Edinburgh Castle. Princeton named an athletic field in his honor and commissioned a portrait of him in his tartan. The John Prentiss Poe Jr. Football Cup, now known as the Poe-Kazmaier Trophy, is awarded annually to the team’s most valuable player.

Accolades and memorials flowed for years following his death. In the style of the day, many tributes were in verse and overwrought. A taste can be had from one reprinted in the New York Herald Tribune in 1925:

When hearts were searched and troth was tried,

And death was yes or no;

When “Hit the line!” meant bayonets fixed

And one more trench to go,

You rode your mud-caked shoes right on,

Just as you used to; though

No honest tackle brought you down:

They killed you, Johnny Poe.

A hero becomes an empty vessel into which we pour our own longings and inadequacies. As Johnny himself would have acknowledged, his was a life full of wandering, searching for glory he never found. Reading his letters from across the years, one finds not someone in love with life, but someone desperately looking for meaning and purpose in a life that seemed to him to provide little of either.

At times, it seemed to haunt him. Alone in the Nevada desert, he once mused on the path he had chosen for himself and hearkened back to the Walter Scott novels he had read as a boy. “Though living side by side with wife deserters, crooks, a child murderer, and some of the scum of the earth,” he wrote his class secretary, “I think the fact of being a Princeton man was a pillar of cloud by day and fire by night in keeping me from sinking to their level, and the knowledge that Old Mother Princeton wishes to believe of her sons as Isabella of Croix did of Quentin Durward: ‘If I hear not of you soon, and that by the trumpet of fame, I’ll conclude you dead, but not unworthy.’”

A decade before he died, Johnny addressed his classmates at their 10th reunion. He quoted from “The Lost Legion,” a favorite poem by Rudyard Kipling. The verse applied equally well to him:

Our Fathers they gave us their blessing;

They taught us, they groomed us, they crammed;

But we’ve cut the clubs and the messes;

For to go and find out and be damned. ![]()

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is a freelance writer and cartoonist, and a frequent PAW contributor.