May 12, 2004: Features

Photography professor Emmet Gowin (Charles Lyon) |

Telling

stories through a lens

Under artist and teacher

Emmet Gowin, students learned to find themselves in their subjects

By Jessica Dheere ’93

Emmet. It would seem, the way students and alumni bandy about the name, that he was the most popular guy on campus. That everyone had taken a class with him. Many wish they had. Emmet Gowin, who won the President’s Award for Distinguished Teaching in 1977, has taught photography at Princeton for 30 years. While he has earned widespread acclaim for his work, from his early family portraits to his recent aerial landscapes, his former students best remember his presence in the classroom and the darkroom.

Gowin is “intellectual and well read but doesn’t have a blueprint for what he’s going to do every semester. He brings the improvisational skills you need as an artist to teaching,” says Laura McPhee ’80, a photography professor herself for the past 17 years at the Massachusetts College of Art. “And he’s demanding. He assumes that his students can jump in the river wherever he is, and swim.”

But that doesn’t mean students must swim like he does. If he’s doing butterfly, they might scissor-kick. “I never have understood what I perceive as a drive and a desire in education to have students reflect the influence of the person they work with,” Gowin says. “Each person is an embodiment of something that they already were. They have a secret inside themselves that they now have to try to polish. I try to help them become more of what they are.”

Many of his students have followed Gowin into lives as artists. Here are views of what some of them are creating today.

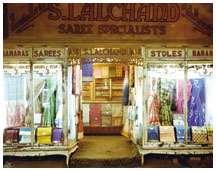

Laura McPhee ’80’s “Saree Shop, Newmarket, Calcutta, India, 1998.” Courtesy Laurence Miller Gallery, New York. |

Laura McPhee ’80

“I’m always improvising,” says Laura McPhee ’80. “It’s part of what I find most thrilling about being an artist.” So after winning a Fulbright fellowship in 1998, the Boston-based McPhee turned her lens away from the decade of landscapes that she and her artistic partner, Virginia Beahan, had photographed for their book No Ordinary Land (Aperture, 1998), and moved with her family to Sri Lanka, where she began shooting full-length portraits of workers who plucked tiny tea leaves in the rural highlands. But her daughter’s asthma precluded them from staying in the countryside.

They moved to Calcutta and McPhee started focusing on the city’s vernacular architecture, ultimately adapting the theme she shared with Beahan – the relationship between humans and the landscape – to explore the relationship between the native and imperialistic cultures that have defined India. In a photo of a saree shop, for example, the vibrant jades, rubies, and lapis-lazulis of the fabrics displayed capture attention, but the signage makes the statement. Deco-style gold-painted lettering reads, “Petticoats,” “Frocks,” “Kimonos,” “Brocades,” “Stoles,” “Velvets,” and, of course, “Sarees.” The things advertised are what the English would have been buying, “but the sarees are the only commodity in the window,” McPhee points out.

From “The Landscape of Sport,” a recent exhibition of panoramic photographs by Elise Wright ’83: top, Pagoda tennis courts, now gone; below, Princeton Stadium. (Photo: Sarah Bodine) |

Elise Wright ’83

She was a history major, but Elise Wright ’83 had a thesis exhibition of her photographs anyway. It consisted of landscapes that she shot around Princeton, near her home in Lambertville, New Jersey. Though it was her grandfather who gave Wright her first camera, “my interest in landscape began with Emmet,” she says. “He shared his concerns and challenges, the questions he was examining, so we shared in his creative process.”

A show of Wright’s work, “The Landscape of Sport,” included panoramic-format color images of a game being played on the rugby fields, the empty Princeton Stadium designed by Rafael Viñoly, and the recently demolished Pagoda tennis courts at the center of campus, which provided the impetus for the project. “Initially the desire was to record spaces on the campus that were disappearing,” says Wright, “but then the landscape of sport evolved. It’s not intended solely to record but to raise questions about how we organize and manage open space and the lengths we go to do that, whether we put up a rope through a stake, or a $46-million stadium.”

|

David Maisel ’84

Portrait of Maisel by Lynn Fontana

A trip to Mount Saint Helens with Gowin in the summer of 1983 left David Maisel ’84 entranced with aerial photography. “It incited my passion for looking at sublime subject matter,” the San Francisco-based photographer says. “The aerial aspect becomes so alien and abstract and the scale so incomprehensible.” In 1985 Maisel drew on this experience, his training in architecture, and his affinity for Robert Smithson’s mine-reclamation works to begin taking aerial pictures of clear-cutting operations in the northern Maine woods, which were followed by a series of aerial images of copper mines. The orange-glowing tailings ponds, among the other physical and chemical alterations to the earth that Maisel observed at the mines, struck him with what he calls their “savage beauty.”

Hovering between reality and abstraction, the pictures in his just-released book, The Lake Project (Nazraeli Press), continue this theme. Taken at various elevations, something Maisel experiments with “as a compositional device” in much the same way that other photographers adjust the focal length of a lens, the four-by-four-foot prints depict Owens Lake in Southern California, which was drained in the early part of the last century, leaving behind a dry bed of minerals and poisons whose bloodred, ocher, and jade hues ominously and gorgeously tint the landscape.

Above, an aerial photograph from The Lake Project by David Maisel ’84, a collection of images that explores California’s Owens Lake and its environs. The lake was drained beginning in 1913 to supply Southern California’s water needs.

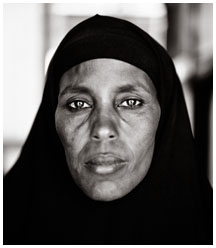

Right, Abshiro Aden Mohammed, a women’s leader in a Somali refugee camp in Degahaley, Kenya. From A Camel for the Son (2000) by Fazal Sheikh ’87. (Photo ©Fazal Sheikh) |

Fazal Sheikh ’87

Rather than flying over the places he photographs, Fazal Sheikh ’87, who lives in Zurich, likes to land and stick around awhile. Gowin always encouraged students “to find out our own responses to situations,” says Sheikh, whose black-and-white photographs have traced his own family’s origins amid contemporary conflicts in northern Pakistan, and documented Somali refugees in Kenya. “So I need to stay for a time to transcend what I know from the media.”

For the past three years, his work has taken him to Vrindavan, India,

the birthplace of Krishna, and the destination of tens of thousands of

widows who, considered inauspicious, are cast out of their homes after

their husbands die. “A rather profound human-rights violation is

being committed against these women,” says Sheikh, who expresses

a desire not to oversimplify the scene. “The women also find a sense

of community here. So, the question is, how do you render an Eastern story

to a Western audience? You have to get to an understanding through individual

stories, to create an emotional space. Get the viewer drawn into that

sense of space or help them see what one of these women might see.”

Or as Gowin might suggest, to help the viewers themselves “become

more of what they are.” ![]()

Jessica Dheere ’93 writes about art, architecture, and design in New York.