December 8, 2004: Features

Henry Martin ’48 with his wife, Edie, and grandson Henry R. McGrath, in a photo taken on Edie’s birthday, Sept. 16.

Neurologist William Leahy ’66, center, with students in a program he created to train certified home-health aides and nursing assistants.

Pam Kunkemueller cared for her husband, Jim Kunkemueller ’61, for 10 years until his death in 1999, six years after this photo was taken. (Photos courtesy Henry Martin ’48; William Leahy ’66; Pam Kunkemueller s’61)

Michelle Preston *86 with her mother, in a happier time, Mother’s Day, 1961.

Michele Domres-Hon *76, left, with her mother and daughter Stephanie. Stephanie, a secondary-school student, is explaining the results of summer research she conducted involving a possible Alzheimer’s vaccine.

Bruce Steiner *56, left, and his partner, Jim Anthony, at the Alzheimer’s Association Public Policy Forum in Washington, D.C., in 1999. (Photos courtesy Michelle Preston *86; Kathy Edwards; Bruce Steiner *56)

|

Caring

for someone with Alzheimer’s

By Katherine Federici Greenwood

Henry Martin ’48 first noticed that his wife was becoming forgetful about a decade ago, when she began to ask the same questions over and over again, and could not remember what she needed at the grocery. One day Martin opened a kitchen cabinet and found 11 boxes of rice. Edie, Martin’s wife of 51 years, had Alzheimer’s disease and Martin became her primary caregiver, with all that it entails. Last spring, when the Martins sat down to a meal of corn on the cob, their first of the season, Edie stared at the cob, uncertain what to do with it. “She picked it up and tried to eat it vertically,” recalls Martin. “I had to explain to her how to do it. I was horrified.”

For years, Henry Martin guided his wife in the once-ingrained routines of daily living that were disappearing from memory. Mornings often began with battles: She resisted getting into the shower; she could not pick out her clothes and she didn’t want his help. Once dressed, they would have breakfast in their residential community’s dining room, but she soon became unable to choose her own meals. They enjoyed after-breakfast walks into town, until she lost interest in walking. So they would spend mornings in their apartment — he doing paperwork, she watching television or just sitting quietly. Time after lunch was spent in much the same way, until she lost interest in reading books and watching TV. Now she just sits a lot.

Three years ago, the daily struggles to bathe her, get her dressed, and give her pills became too exhausting for Martin. Staff members at their retirement community in Pennsylvania recommended that she move out of their apartment and into the dementia unit. “I was relieved,” says Martin, who for 45 years drew cartoons for the New Yorker magazine. But he was also deeply sad. “I’ve lost a really huge portion of her. At times there are glimmers of her old sense of humor and there are moments she can recall events, but those moments are few and far between,” he says. “There is a person there, but it’s not the one you spent your life with.”

Seventy percent of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease live at home, including many who are cared for by aging spouses like Martin, or by adult children raising their own families at the same time. The great majority of caregivers — 75 percent, according to a 1999 report of the Alzheimer’s Association and the National Alliance for Caregiving — are women, who are likely to care not only for their own parents, but for their in-laws as well, says Laura Holly-Dierbach of the Alzheimer’s Association Greater New Jersey chapter. About 4.5 million Americans, including 10 percent of those over 65, have the disease, and the number appears destined to grow as people live longer.

Patients can live for three to 20 years with Alzheimer’s, a disease in which nerve cells in areas of the brain involved in thinking and memory degenerate and die. Its progression varies but early symptoms generally include memory loss, difficulty performing familiar tasks, and misplacing things. Over time patients usually have trouble with activities of daily living, such as balancing a checkbook and bathing. By the late stages patients may have difficulty swallowing and walking, be unable to recognize family and friends, and experience profound changes in personality and mood.

The physical and emotional toll on caregivers, many of whom are elderly themselves, can be enormous. [One popular guidebook for caregivers is aptly named The 36-Hour Day (Warner Books, 2001)]. Dealing with a loved one who may no longer recognize you, and whose gentle demeanor may change into one that is spiteful, combative, or hostile, can be emotionally draining. “Sometimes it’s more difficult for family members to watch their loved one go through Alzheimer’s than it is for the person who is actually experiencing the disease,” says Holly-Dierbach. In addition to the sadness that arises from watching a loved one deteriorate, caregivers often find themselves isolated, cut off from friends and activities, because they lack the time, energy, and opportunity to interact socially. William Leahy ’66, a neurologist outside Washington, D.C., cares for patients with Alzheimer’s and other degenerative diseases, but notes that he often ends up treating their caregivers, who suffer back pain, hypertension, ulcers, depression, and stress-related coronary disease.

Financial burdens exacerbate the emotional and physical difficulties. Medicare doesn’t cover the cost of nursing homes, room and board in assisted-living communities, adult day care, or round-the-clock care in the home; Medicaid doesn’t kick in until someone has exhausted most personal resources. Meanwhile, a skilled-nursing facility can cost up to $10,000 per month, and a home health aide about $20 per hour.

Pam Kunkemueller cared for her husband Jim Kunkemueller ’61 for 10 years before his death in 1999 at age 59 of early-onset progressive supranuclear palsy, a disease whose symptoms mimic Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. She eventually had to help lift her 6-foot 5-inch, 200-pound husband from chair to bed, and help him get in and out of a car. Although physical and occupational therapists helped her learn how to care for him, and she hired home health aides to assist, she did the bulk of the physical work until the last 23 months, when he moved into a nursing home. The stress and lifting took their toll, aggravating her high blood pressure and leading to anxiety and depression, for which Pam Kunkemueller took medication. “I look back and wonder how I got through those 10 years,” says Kunkemueller, who now helps run the Alzheimer’s support group she first visited in the early days of her husband’s illness. She also serves on the board of the Alzheimer’s Association Massachusetts chapter, volunteers on its telephone helpline, and offers educational programs to families of newly diagnosed patients. “No one person can [manage] Alzheimer’s disease alone,” she says.

About one-third of caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients have children or grandchildren under the age of 18 living at home. Middle-aged parents feel squeezed between caring for their children and for their adult parents, and managing their careers along with the physical, emotional, and economic costs of the disease. “You are taking middle-aged people who have no training at all and throwing them into a very demanding situation,” says Leahy, who has written a manual for baby boomers, Caregiving: A Guide To Making It Work, which will be published by Hartman Publishing next year, and created a program to train high-school students as certified home-health aides and nursing assistants for patients with Alzheimer’s and other progressive illnesses.

“I think I probably was depressed. I wasn’t aware of what I was doing and what I was not doing,” says Michelle Preston *86, reflecting on the three years she spent juggling the needs of her three children and those of her mother, who has a type of vascular dementia called Binswanger’s disease and shows signs of Alzheimer’s. Preston, a former PAW editor who lives near Princeton, stopped home-schooling her 15-year-old daughter, in large part because her mother’s illness required so much time and attention. Phone calls from her mother, many of them abusive, would begin at 8 a.m. and continue throughout the day and late into the night, disrupting the entire family. Her mother threatened suicide and once made a serious attempt; each episode brought Preston running to her side. Last spring her mother’s psychotic behavior subsided, and other symptoms, such as forgetfulness, and an inability to balance a checkbook or read and write, became more pronounced. Her mother, who now lives in an assisted-living facility, usually calls only once a day, but Preston still manages her care and her financial matters and sees her at least once a week.

An English teacher and mother of three, Michele Domres-Hon *76 turned down full-time teaching positions and reduced her work schedule to care for her mother, who has Alzheimer’s. Domres-Hon, who has two sisters, one a physician in California and the other an accountant in Pennsylvania, volunteered to take over the care of her mother about two years ago, when the sisters determined that their mother’s forgetfulness and confusion were not normal. They moved their widowed mother against her will from Syracuse, N.Y., into Domres-Hon’s home in Florida.

For six months her mother lived with Domres-Hon, her husband, and youngest child. Her mother couldn’t be left alone for long because she might leave a stove burner on or wander out of the house. Domres-Hon would bring her along to her daughter’s soccer games, but her mother, in the early stage of the disease, didn’t want to be a burden and didn’t like tagging along. So she moved into a retirement community, just two miles from Domres-Hon’s house.

Today, Domres-Hon spends about three hours daily with her mother, taking her to doctor’s appointments, shopping, and to the hairdresser, and managing her medications, doing her laundry, and just spending time with her. Her mother doesn’t need help with bathing or dressing, but she has lost the ability to reason clearly, make decisions, and remember verbal instructions. Helping her mother navigate certain situations has been particularly frustrating for Domres-Hon: If her mother goes on a community bus trip, will she remember to board the bus to return? Will she lose her purse and money?

For adult children caring for their parents, who become childlike as the disease progresses, Alzheimer’s — which has been called the “long goodbye” — can fundamentally change the nature of their relationship. For Domres-Hon, it has been most difficult to acknowledge the end of the emotional connection with her mother, which has disintegrated with the loss of short-term memory. “You have this emotional absence of your parent because you can’t share things that you used to share,” she says. “You sort of feel like that person isn’t there for you anymore. ... It’s easier to think of this as a different person — someone like your mother, but different.”

With the growing number of Alzheimer’s patients, Holly-Dierbach has seen an increase in the need for respite care so that caregivers can get a break, get out of the house, and possibly go to work. Barbara Yost, executive director of Princeton HomeCare Services in Princeton, also has seen a greater need for relief, particularly during the last six months of a patient’s life, when, she says, caregivers are exhausted and the patient needs even more help.

Unlike most family caregivers who assume the role of caregiver after a lifetime of personal connection to the patient, Bruce Steiner *56 and his partner, Jim Anthony, became a couple after Anthony already had been diagnosed with the disease, in 1996. “I was relatively naïve at that point,” says Steiner, who is divorced and has two grown children. “I don’t think you really understand what you’re getting into until you get into it.” At that point, Anthony, who has no children and one brother in Tucson, Ariz., was in the very early stages of the disease. Steiner, who has a Ph.D. in chemistry, concluded that life with Anthony was much better than life without him, and four years ago he retired from his job at the National Institute of Standards and Technology to be home with Anthony in Sudbury, Mass., full-time.

Today Steiner has to guide Anthony, a former English professor, through almost everything he does: bathing (Anthony forgets that he needs to rub the soap on his skin and to rinse off soap suds), dressing (Anthony doesn’t know a shirt’s front from its back, or its top from its bottom), and eating. Anthony, whose eyesight is failing and who has forgotten the words for many things, may not see a fork on the table in front of him. “At times you have to deal with him almost as a blind person,” says Steiner. “I almost have to put his hand on the fork for him to see it.”

Anthony’s easygoing personality has eased the caregiving burden,

says Steiner. “Jim is still a lot of fun to be with and we kid each

other a lot — we always have, and that humor takes you a long way,”

says Steiner. They are still active, attending exercise classes, Quaker

meetings, and a social group for older gays, among other activities. “Different

people look at a glass as half full or half empty,” he says. “If

you look at it, there’s a lot of water still in our glass, so it’s

a matter of focusing on that.” ![]()

Katherine Federici Greenwood is an associate editor at PAW.

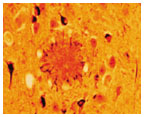

The brain of an Alzheimer’s disease patient contains two types of abnormal structures: Amyloid plaques (sunburst-like structure), which contain beta-amyloid fibrils, and neurofibrillary tangles (smaller, dark structures). Stopping the formation of one or both of these structures may prevent the onset and progression of the disease.

Postmortem human brains from a cognitively normal indivudual, left, and from a patient who died with Alzheimer’s disease. Note the marked atrophy of the brain in the Alzheimer’s-disease patient. (Photos courtesy Peter Lansbury ’80; Jeff Stock; Bruce Yankner ’76)(Photos courtesy Robert Tycko ’80; Michael Hecht) |

Understanding Alzheimer’s

Doctors used to think that dementia was a normal part of aging. But scientists now know that that isn’t the case, and they identified the two main hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease in the brain: amyloid plaques, which are clumps of protein fragments, and neurofibrillary tangles, which are twisted strands of another protein. These plaques and tangles are involved in destroying certain neurons and their ability to “talk” to each other.

Most scientists believe that plaques form before tangles, and that if you could prevent plaque formation in the brain, people wouldn’t develop Alzheimer’s. There’s no cure, and available medicines remain largely ineffective; they treat symptoms for a short time and don’t stop the underlying degeneration of brain cells. Many scientists, including professors at Princeton and Princeton alumni, are trying to unravel the mysteries of the disease. Here are some of them:

Robert Tycko ’80,a chemist at the National Institutes

of Health in Bethesda, Md., studies the molecular structure of amyloid

fibrils, the main component of the amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s

disease. Amyloid fibrils are produced when protein fragments, called A-Beta

peptides, are snipped off from a larger protein, called amyloid precursor

protein (APP), faster than the body can clear them, and they bunch together.

Although the precise mechanism by which amyloid plaques contribute to

Alzheimer’s disease is a subject of scientific debate, some researchers

believe that these plaques convert oxygen into hydrogen peroxide, which

corrodes parts of the brain involved in thinking and memory, causing the

brain cells to degenerate and die.

Robert Tycko ’80,a chemist at the National Institutes

of Health in Bethesda, Md., studies the molecular structure of amyloid

fibrils, the main component of the amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s

disease. Amyloid fibrils are produced when protein fragments, called A-Beta

peptides, are snipped off from a larger protein, called amyloid precursor

protein (APP), faster than the body can clear them, and they bunch together.

Although the precise mechanism by which amyloid plaques contribute to

Alzheimer’s disease is a subject of scientific debate, some researchers

believe that these plaques convert oxygen into hydrogen peroxide, which

corrodes parts of the brain involved in thinking and memory, causing the

brain cells to degenerate and die.

“The molecular structures of amyloid fibrils have been mysterious for decades,” says Tycko. But using new nuclear magnetic resonance techniques, he has determined a nearly complete model for the molecular structure of the amyloid fibrils. His structural model may help other scientists develop drugs to interfere with the formation of amyloid fibrils and plaques, slowing or stopping the progression of the disease.

Michael

Hecht, a Princeton professor of chemistry whose lab

focuses on protein design, is studying the A-Beta peptides that bunch

up to form amyloid fibrils and plaques. He’s looking at the sequence

of A-Beta’s 42 amino acids to determine why that particular sequence

has a propensity to bunch up or aggregate. (A protein is a chain of amino

acids.)

Michael

Hecht, a Princeton professor of chemistry whose lab

focuses on protein design, is studying the A-Beta peptides that bunch

up to form amyloid fibrils and plaques. He’s looking at the sequence

of A-Beta’s 42 amino acids to determine why that particular sequence

has a propensity to bunch up or aggregate. (A protein is a chain of amino

acids.)

Hecht is developing a screening method that can determine what change in sequence of amino acids will prevent A-Beta from aggregating. In a petri dish, he joins a mutated A-Beta peptide to a green fluorescent protein; if the mutation prevents aggregation, then the fused protein looks green. When he finishes fine-tuning this method, a drug company could use it to screen its library of potential drugs to see if any of them prevent clumping of A-Beta peptides, and therefore prevent the formation of amyloid plaques.

Peter

Lansbury ’80, professor of neurology at Harvard

Medical School, thinks that it’s not the amyloid plaques that cause

brain cells to die, but what happens along the way to the formation of

the plaques. In fact, he believes the plaques, which under an electron

microscope look like rope — an ordered structure, not just a pile

of undigested protein — are a logical way for the body to get rid

of the A-Beta peptides.

Peter

Lansbury ’80, professor of neurology at Harvard

Medical School, thinks that it’s not the amyloid plaques that cause

brain cells to die, but what happens along the way to the formation of

the plaques. In fact, he believes the plaques, which under an electron

microscope look like rope — an ordered structure, not just a pile

of undigested protein — are a logical way for the body to get rid

of the A-Beta peptides.

“It’s not the fact that you have amyloid plaque in the brain that’s the problem. It’s the fact that you made it,” he says. His lab is looking at smaller aggregates of A-Beta peptides, called protofibrils, that are generated before the fibrils form, as the body makes amyloid plaque. The protofibrils may poke holes indiscriminately in the membranes of brain cells, which ultimately kills the cells. He’s trying to understand how protofibrils, which may form 20 years before a person shows symptoms of the disease, make pores in membranes. Eventually he hopes to help develop a drug to prevent pore formation or a drug that would help the body make fewer A-Beta peptides or get rid of the protein clumps more quickly and efficiently.

Jeff

Stock, a professor of molecular biology at Princeton,

is focusing on neurofibrillary tangles, also called tau tangles. If you

could block tangle formation, he says, the amyloid plaques might not be

harmful to the brain.

Jeff

Stock, a professor of molecular biology at Princeton,

is focusing on neurofibrillary tangles, also called tau tangles. If you

could block tangle formation, he says, the amyloid plaques might not be

harmful to the brain.

The main component of the tangles is tau, a protein that normally stabilizes a cell’s internal “skeleton.” Tangles form when an enzyme, called PP2A, fails to remove phosphate groups (which are proteins) from the tau protein. Tau proteins bunch up, forming insoluble twisted fibers, which cause the transport system in the neurons to collapse and disrupt the neurons’ ability to “talk” to each other and to send nutrients and messages back and forth.

Stock, whose grandmother died of Alzheimer’s, is searching for extracts from common herbs and plants that inhibit the formation of tangles by encouraging PP2A to remove phosphate groups from tau. He started with an extract from coffee beans, because studies have shown that people who drink lots of coffee are less likely to get Alzheimer’s.

Bruce

Yankner ’76, professor of neurology and neuroscience

and director of the Program in Neurodegeneration at Harvard Medical School,

discovered in 1990 that amyloid plaques were toxic to neurons and not

just innocuous by-products of the disease. He is now trying to better

understand the aging processes in a normal brain in order to better understand

Alzheimer’s.

Bruce

Yankner ’76, professor of neurology and neuroscience

and director of the Program in Neurodegeneration at Harvard Medical School,

discovered in 1990 that amyloid plaques were toxic to neurons and not

just innocuous by-products of the disease. He is now trying to better

understand the aging processes in a normal brain in order to better understand

Alzheimer’s.

“The major gap in understanding Alzheimer’s,” says Yankner, “is understanding why it’s a disorder of the aging brain.” Most aged brains contain plaques and tangles, but at low levels, he says, suggesting that they are a normal part of the aging process. His theory: Alzheimer’s is an “exaggerated aging process.” The brains of people who don’t develop Alzheimer’s and other age-degenerative diseases, such as Parkinson’s, are better able to repair the genes that are damaged during the aging process, says Yankner.

Yankner studied gene patterns in postmortem brains of 30 people, aged 26 through 106, who did not have Alzheimer’s or other types of dementia. He found that only 4 percent of genes in the brain change as people age. Genes involved in memory, learning, and communication between neurons were among the most damaged, and were particularly vulnerable to free radicals, toxic by-products of the oxygen we breathe. Now his lab is trying to determine why memory genes are more vulnerable than other genes in the aging brain.

“If you want to prevent Alzheimer’s, as opposed to just

treat it, you want to do something when people are younger, years before

they get the disease,” says Yankner. To that end, his lab is investigating

potential drug and gene therapy approaches to prevent the DNA damage that

occurs with aging. He believes the day will come when doctors will genetically

profile their patients to determine who is at risk for a host of age-related

disorders, including Alzheimer’s, and be able to initiate treatments

or lifestyle changes that would prevent gene damage that leads to these

diseases. “I believe that a genomic approach to medicine will materialize

in our lifetime,” he says. ![]()

By K.F.G.