Have an opinion about this issue of PAW? Please take a minute to click here and fill out our online questionnaire. It’s an easy way to let the editors know what you like and dislike, and how you think PAW might do better. (All responses will be kept anonymous.) |

April 6, 2005: Features

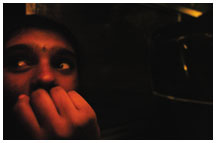

Pathma on the overnight bus from Sri Lanka’s capital city, Colombo, to Komari, where she would be reunited with her parents for the first time since the tsunami struck on Dec. 26, 2004. The 150-mile trip takes more than 10 hours. Sri Lankans pray in the last light of day at a ceremony for tsunami victims at the Kalutara Bodhi Temple in Kalutara, Jan. 26. More than 30,000 people attended the Buddhist ceremony, which took place exactly one month after the disaster.

Above, men dig ditches to bury a water pipe in a refugee camp where more than 4,000 people are living in tents in Mandaan.

A child in a refugee camp in Komari receives a new backpack and school supplies from a private organization called Rebuild Sri Lanka, which was founded by Sri Lankan business people in response to the disaster. “It didn’t matter if a boy got a pink Barbie backpack or a girl got a blue Spiderman backpack; there were no complaints,” recalls photographer Anne Sherwood ’92.

A woman burns debris outside her makeshift home in Arugam Bay. Pathma’s father and family members grieve over the loss of two children. Says photographer Sherwood: “Pathma’s family was incredibly kind to me. They would have given me anything and yet they lost everything.”

Ann Sherwood ’92 standing amid rubble and debris on a Sri Lanka beach. |

After the horror, humanity

Photographs and text by Anne Sherwood ’92

The standing-room-only bus rattled across Sri Lanka three weeks after a tsunami killed 35,000 people along the country’s coastline in 20 minutes. I was sharing a seat with a 14-year-old Tamil girl named Pathma, who on the day of the tragedy was hurled through the water, the debris of her village slashing her abdomen.

After the tsunami, Pathma had taken a 10-hour bus ride with an uncle to a hospital in Colombo, the nation’s capital. By the time of the return trip, Pathma’s physical wounds were healing nicely. Her emotional wounds remained raw.

How does one recover from an event as massive, destructive and deadly as December’s tsunami? It’s a question I pondered in my time traveling around Sri Lanka photographing the devastation and the relief effort.

Pathma was returning home, but home as she knew it no longer existed. On the morning of Dec. 26, family members were in their brick house when the first wave struck their tiny village of Komari, on the eastern coast of Sri Lanka. Their modest home was almost a quarter of a mile from the Indian Ocean, but the wave flooded the village like a tidal surge. Pathma’s father grabbed his two small children and hopped on a bicycle, his wife and Pathma running behind. They all tried to outrun the sea.

When the second wave came — it was “as tall as the coconut trees,” Pathma’s father said — it crashed into the family as they crossed the village bridge. The wave destroyed the bridge, ripped the children from their father’s arms, and sent Pathma into a roiling ocean of flotsam. Her 4-year-old sister, Sadurja, and 8-year-old brother, Delakshan, were never found. Pathma’s parents lost everything except her. They now survive in a refugee camp about a mile from Komari.

I had been in Sri Lanka almost a week when I met Pathma’s parents. I’d begun my journey in the south, where I saw decomposing bodies floating in a lagoon, fishing boats in the middle of town squares, and a train in which 1,000 people had drowned. Then I made my way to the east coast, where the waves had struck with the most force.

I was traveling in Tamil territory, a region occupied by ethnic rebels until a cease-fire in 2002 reunited the country. Two decades of civil war had separated the Tamil-dominated east and north from the Sinhalese-controlled south and west. Now the dire need for humanitarian aid had sent Sri Lankans into areas they’d never considered visiting before the tsunami.

For the most part, Komari looked like the other villages I’d seen — leveled, decimated, as though it had been bombed. But unlike in other villages, I didn’t see anyone cleaning up or thinking about rebuilding. The only surviving buildings were the Hindu temple and the Christian church. Every single home — about 400 of them — had been reduced to rubble. Komari was completely deserted.

When I met Pathma’s parents — their daughter was still in Colombo — they seemed to be in shock, emotionless. I found it extremely difficult to talk to people about so much loss. Her father told me, “We can rebuild our house, we can rebuild our business, we can rebuild our savings, but we can never make these children again.”

The second day I went to visit, I found the family sitting in their makeshift tin hut at the camp. There were suitcases by the door. Relatives from the north had arrived by bus, not knowing who had died and who had survived in Komari. They had just learned that Pathma’s sister and brother were missing. Everyone was crying. I sat down and listened and, at times, I cried too.

I spent several days with Pathma’s relatives in my attempt to understand the impact of the disaster. Through their pain and struggle I began to put a human face on 35,000 deaths. I went back to the village and found their house, which they couldn’t yet muster the courage to visit. I dug through their waterlogged belongings and salvaged what I could: family photographs, a calendar, medical records, and a school uniform still in the plastic bag. I took these back to the camp. In one of the photographs the salt water had erased the entire scene except for the face of a little boy. When I gave the picture to Pathma’s grandmother, she burst into tears. It was her lost grandson.

After a week in the east I returned to Colombo, where Pathma had been staying with her uncle after receiving medical care. I went to find her. She and her uncle planned to go to Komari later in the week, and I arranged to join them on the journey.

Before we got on the bus, Pathma painted her fingernails and placed a bindi — the ornamental mark applied by Hindu women and girls — between her brows. It had been three weeks since she had seen her parents, three weeks since she had lost her siblings. She stared out the window while we rolled past tea plantations and through little towns on the 150-mile journey.

At 6:30 a.m. the bus stopped in front of the refugee camp outside Komari. We stumbled into the darkness. Her mother must have been listening intently for the sound of the bus, because she met us halfway to the hut. She gave Pathma a quick kiss and led her to their temporary home. Pathma greeted her family, showed off her scars, and moved around the camp nervously.

Later in the day we went to see the village and the family’s ruined house. We walked across the new bridge, which had just been opened, stopping at the point where Pathma last saw her brother and sister. Soon after that, Pathma sat on the ground and put her head on her arms. She told me she didn’t want to stay in Komari. She was afraid of the sea, and she wanted to move to Colombo and go to school there. She wanted to forget what had happened, but every night she wakes up screaming, dreaming of the waves.

On my last day in Komari, I went to say goodbye to Pathma and her parents. Life in the camp was becoming routine, and it was hard not to imagine that the entire village still would be displaced in a year.

But Pathma’s father looked at me and said, “I went to the house today to look for a tractor so I could start cleaning up. There was no tractor. But I will go again tomorrow and the next day and the next day.”

And Pathma had decided to stay in Komari. The school was still closed, but there were a couple of bulldozers moving rubble around the courtyard. It was a start.

Three weeks after hundreds of thousands of people in 11 countries were stolen in the morning sun by a lethal wave, one wall of a classroom at the Komari school remained standing. Scrawled in chalk across the green board, someone had expressed what everyone felt:

“Tsunami, please don’t come again.” ![]()

Anne Sherwood ’92 is a freelance photojournalist who lives in Bozeman, Mont. To view more of her work, visit www.annesherwood.com.