Have an opinion about this issue of PAW? Please take a minute to click here and fill out our online survey. It’s an easy way to let the editors know what you like and dislike, and how you think PAW might do better. (All responses will be anonymous.) |

July 6, 2005: Notebook

Oxman ’67 to lead board’s executive committee

On screen: unscripted and undressed

More

students to major in smaller departments

More

students to major in smaller departments

Dean: University’s campaign shows ‘very encouraging’

results

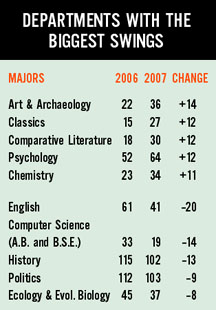

In the first measure of the University’s effort to encourage students to consider a wider range of majors, 12 of the 15 smallest departments show more incoming majors than a year ago.

Dean of the College Nancy Malkiel had urged students to look beyond the five largest departments — politics, history, economics, the Woodrow Wilson School, and English — in making their selections. Students could enjoy “much easier access” to senior faculty and prepare just as successfully for their careers, Malkiel said, by following their “intellectual passion” and not simply picking a major that was popular.

When sophomores declared their majors in late April, four of the five big departments lost majors. The five most popular majors account for 40.3 percent of the 1,166 students in the Class of 2007, compared to 42.3 percent of the Class of 2006 and 44.5 percent of the Class of 2005. During her annual talk with alumni at Reunions, President Tilghman said the growth in smaller departments “is generally a very, very good thing for Princeton.”

Professor Claudia Johnson, English department chairwoman, said her department had been “disproportionately” affected by the University’s campaign, with the number of sophomore concentrators dropping to 41 from 61 the previous year. “We’re a successful department, but it seems the University is trying to undo some of that success,” Johnson said. While she said she is sympathetic to the smaller departments, she said it is “patently untrue” to say that English majors do not receive “close, individual attention.”

“I count these returns as very encouraging, but a first step,”

Malkiel said. She said the effort will continue, including the sending

of a 71-page publication, “Major Choices,” to members of the

Class of 2009 and their parents. The booklet, which includes interviews

with alumni who majored in smaller departments, was first distributed

last year. The University is investing about $400,000 to help a number

of departments to create or revise courses as part of the initiative,

Malkiel said. ![]()

By W.R.O.

(Photographs by Beverly Schaefer) |

During her annual “conversation with alumni” at Reunions,

President Tilghman highlighted the University’s accomplishments

in 2004--05, including what she called a historic moment: The Class of

2005 is the first to graduate debt-free as a result of changes to Princeton’s

financial aid policy. And she shared her most pressing concern —

that federal cutbacks in funding university research, particularly in

science and engineering, will negatively affect both scientific discoveries

and the dominance of the United States as a world power. “That’s

what keeps me up at night,” she said. Asked about the University’s

position on the unionization of graduate students, Tilghman replied that

the graduate student government sees no reason to unionize because Princeton

provides both financial and intellectual support. “Any complaint

is that there are not enough opportunities to teach, not that they are

asked to teach too much,” she said. To hear an audio version of

the talk, go to http://tigernet.princeton.edu/Events/Reunions.asp.

![]()

Oxman ’67 to lead board’s executive committee

Stephen Oxman

’67 |

Princeton’s Board of Trustees has eight new members and a new leader: Stephen Oxman ’67, who replaced Robert Rawson ’66 as chairman of the board’s executive committee on July 1.

Oxman, of Short Hills, N.J., is a senior adviser at Morgan Stanley. He received the Pyne Prize as a Princeton senior and went on to earn a law degree at Yale and a doctorate at Oxford, where he was a Rhodes scholar. Oxman served as assistant secretary of state for European and Canadian affairs during the Clinton administration and worked with the State Department during the Carter administration. He has served on the Princeton board since 2002.

Rawson had been a trustee for 20 years, including 13 as chairman of the executive committee. President Tilghman said he “provided extraordinary leadership as he helped shape and realize dramatic improvements that have transformed this University,” and the trustees have named a freshman seminar in his honor.

The new trustees are:

Thomas Barron ’74, an author and private investor from Boulder, Colo.

Y.S. Chi ’83 of Princeton, vice chairman of Elsevier, a scientific publisher.

Jose Huizar *94, an attorney who is president of the board of education for the Los Angeles Unified School District.

Randall Kennedy ’77, of Dedham, Mass. He is a professor at Harvard Law School.

Matthew Margolin ’05, of Portola Valley, Calif. Margolin was president of the Undergraduate Student Government in 2004-05 and received the Class of 1901 Medal, which goes to the senior who, in the judgment of his or her classmates, has done the most for Princeton.

Katherine Marshall *69 of Washing-ton, D.C. She is a director at the World Bank and counselor to its president.

Nancy Peretsman ’76, executive vice president and managing partner of Allen & Co., a New York investment banking firm. She lives in New York City.

Kimberly Ritrievi ’80 of St. Petersburg, Fla., who recently retired from her post as director of research at Goldman Sachs.

The 40-member board is responsible for the overall direction of the University. It approves the budget, supervises investment of the endowment, and oversees long-term physical planning. The trustees also approve changes in major policies, tuition and the hiring of faculty members.

The new members succeed Rawson and seven others who have left the board:

Elizabeth Duffy ’88, William Ford Jr. ’79, Wesley Harris *68,

Jin “P.J.” Kim ’01, Richard Krugman ’63, Robert

Murley ’72, and Paul Wythes ’55. Wythes led the task force

that recommended the current initiative to increase undergraduate enrollment.

![]()

Blowing out the candles of McCarter Theatre’s 75th anniversary cake are, from left, William W. Lockwood Jr. ’59, director of special programming; Jeffrey Woodward, managing director; and Emily Mann, artistic director. At right is comedian Lily Tomlin, who headlined McCarter’s anniversary gala April 16. (Beverly Schaefer) |

The University’s increasing emphasis on the performing arts is leading to a stronger connection with McCarter Theatre as the theater celebrates its 75th anniversary.

A $150,000 Ford Foundation grant that will bring a nationally known playwright to teach undergraduates while writing a play to premiere at McCarter is the latest sign of cooperative ventures between the two institutions. “It’s a mutually beneficial relationship,” said Emily Mann, McCarter’s artistic director. “We help each other make things happen.”

The most visible sign of this is the 360-seat Roger S. Berlind ’52 Theatre, which opened in 2003 as a second stage for McCarter and as a performance space for the University’s Program in Theater and Dance. The University, McCarter, and Berlind each contributed a third of the $14 million cost. The University maintains the McCarter facilities and provides a “modest” cash grant, said Jeffrey Woodward, managing director.

McCarter, built as a home for the Princeton Triangle Club and now operated

by an independent board, has had a long and star-filled history in theater,

music, and dance. It draws about 180,000 people to more than 300 performances

a year. During Mann’s tenure, McCarter received the 1994 Tony Award

for Outstanding Regional Theatre and has emphasized creating and producing

new plays (two are on the schedule for the coming year). Woodward said

the theater is planning a campaign to increase its endowment from $5 million

to $15 million. ![]()

By W.R.O.

Breaking

ground: synthetic biology

Programming

cells, in a petri dish

Weiss: “The upside is tremendous ... but we have to be

careful.”

Assistant professor Ron Weiss and his colleagues hit the bull’s-eye with an experiment in cell-to-cell communication. Sender cells, center, produce a chemical that activates fluorescence in receiver cells, depending on their proximity to the sender. (photos courtesy Ron Weiss) |

Imagine the possibilities if scientists could find a way to program cells as if they were computers. Custom-designed sensors could be injected to detect diseases, targeted treatments could attack an illness at its source, and specified cells could generate tissues to repair vital organs or even to regenerate an injured spinal cord. It may seem like science fiction, but in the laboratory of Ron Weiss, assistant professor of electrical engineering, experiments in “synthetic biology” are bringing the first steps of programmable cells to life.

For the past eight years, dating back to his time as a graduate student at MIT, Weiss has been successfully programming cells to complete rudimentary tasks. His method involves inserting DNA into bacteria cells, making the cell create specific proteins. The proteins act as switches or logic gates, like those in a computer circuit, and can be arranged to perform specific functions.

Metabolically, individual cells have a limited capacity for creating the proteins needed for computing — each bacterium can create about 500, in addition to the proteins it creates naturally. But if cells can communicate with each other, the potential for more complex computation grows. Weiss’ most visually striking experiment, a collaboration between Princeton and Caltech researchers that was published in the April 28 issue of Nature, demonstrated communication between programmed cells. Cells were programmed to emit a fluorescent protein in response to their proximity to sender cells that produced a chemical to trigger the fluorescence. One type of receiver cells was designed to turn red in close proximity to the sender cells, while another type was set to turn green if they were farther away. The cells, evenly dispersed in a Petri dish, would react only at the appropriate distance from the sender. “In theory,” Weiss says, “you should be able to generate something that looks like a bull’s-eye.”

The results supported his theory, and Weiss used the same cells and principles to create other geometric designs, with brilliant results that even nonscientists could enjoy. “Several years ago, when I used to talk about this work, it was really abstract – what does it mean to have ‘digital computation’?” Weiss says. “When you show images, I think it connects with people quickly.”

Weiss first became interested in synthetic biology when he was a computer science graduate student. His previous work had involved more traditional work with computer circuits. Changing tracks midway through his studies was a risk — and, in the eyes of his Ph.D. adviser, not one worth taking. But Weiss followed his fascination and now works at the vanguard of a rapidly expanding field.

Medical applications top the list of possible uses of synthetic biology. Though there are no current applications, sensing technology seems to be the most realistic short-term goal, with therapeutic treatments and tissue engineering farther down the line. But as technology advances, so do the concerns about using it properly. “The upside is tremendous — the ability to care for diseases and fix problems we were not able to fix before, ” Weiss says. “But we have to be careful.” Weiss and his colleagues in synthetic biology discussed bioethics at the field’s first major conference last year at MIT. Bioterrorism is another concern, though Weiss says that programming cells could be used to combat or disarm a biological threat by terrorists.

In his current work, Weiss is exploring several areas, including turning

the expression of fluorescent proteins on and off in the stem cells of

mice, a first step in the effort to differentiate stem cells for use in

engineering specific tissues. Another project aims to detect small amounts

of the chemicals secreted by pseudomonas aeruginosa, a type of

bacteria implicated in cystic fibrosis. Weiss also works with the next

generation of synthetic biologists in a 10-week summer program for undergraduates

that spans 15 universities. As the field grows, so does the potential

for applications. Says Weiss: “We’re just scratching the surface

of what we can do.” ![]()

By B.T.

Click here for more color images from the research of Assistant Professor Ron Weiss.

The University has selected a British architect described as a “high-tech historicist” to design the chemistry building that will be built on the Armory site. Michael Hopkins and his London-based practice, Hopkins Architects, are noted for their use of “traditional materials in an innovative way” and their energy-efficient designs, said University architect Jon Hlafter ’61 *63.

The size of the building is expected to be about 250,000 square feet. Construction is expected to begin in two to three years and to be completed by 2010. The new building will replace the 76-year-old Frick Laboratory, which department chairman Robert Cava termed “labyrinthine.”

The chemistry building will become part of the University’s “neighborhood” of related science departments. “Many of the best problems in science are interdisciplinary,” Cava said. “We have to be interacting with other people.”

The head of a group that looked at the future of the chemistry department, Graduate School Dean William Russel, said recent faculty departures and anticipated retirements are likely to create a dozen vacancies over the next decade. A new building will support efforts to “rebuild the department and propel Princeton chemistry into the upper ranks of chemistry departments,” said Russel, who is a professor of chemical engineering.

Supporting the cost of construction will be royalties from the patent for Alimta, a cancer-fighting drug developed in part by Professor Edward C. Taylor, who taught at Princeton for 43 years before transferring to emeritus status in 1997. The University holds the U.S. patent and licensed the rights to Eli Lilly & Co. Alimta won FDA approval last year for use against mesothelioma and certain other forms of lung cancer and has shown positive results in treating a variety of other tumors.

“We’re very proud of this patent, because it came out of

precisely the kind of fundamental research that we prize so much here,”

said Provost Christopher Eisgruber ’83. Eisgruber said Taylor’s

research, which began several decades ago in probing the pigments in butterfly

wings, led to “a wondrous discovery.” He said it was a fitting

use for the University to apply royalties it receives to a new building

“to allow us to continue the type of research that Ted Taylor would

want to do.” ![]()

By W.R.O.

Princeton High School senior Michelle Chen will be a member of the University’s

Class of 2009 after graduating from the Princeton University Preparatory

Program. A graduation ceremony for 18 students June 2 was the second for

the program, which prepares academically talented, low-income students

from high schools in Princeton, Trenton, and Ewing for admission to selective

colleges. The program includes summer classes and a year-round writing

course. (Frank Wojciechowski) ![]()

On screen: unscripted and undressed

Charlie Alden ’04, above, in the role of student nudist Henry Grendimeer, plays board games in the buff in the film Naked Princeton. Directors Brittany Blockman ’03 and Josephine Decker ’03 first screened the film in New York in May. (photos courtesy Josephine Decker ’03) |

After the Reunions fireworks on May 29, more than 150 revelers headed to an auditorium in McDonnell Hall for entertainment of a different stripe: the campus debut of Naked Princeton, a short mockumentary film directed by Brittany Blockman ’03 and Josephine Decker ’03.

Despite its enticing title, the directors said that the movie, which began making the rounds at independent film festivals in May, is about expression and freedom in a nonsexual way. In most scenes, everyday objects shield the actors’ most private regions. But at the behest of the Alumni Council, Blockman and Decker agreed to screen the film in the evening and to make sure no one under age 18 was admitted.

The plot is relatively simple: A group of insurrectionary Princeton students, oppressed by a ban on campus nudity, create a nudist society that holds secretive meetings in the buff. The film chronicles the intrigues of the society and tracks the involvement of comically stereotypical campus characters, from the ditzy student government candidate to the conservative fussbudget who tries to derail the nudists.

The inspiration for the movie came from a real-life suppression of campus nudity, the University’s 1999 decision to ban the Nude Olympics. “For both of us, the Nude Olympics were a deciding factor in our choice of college – no joke,” said Blockman, who has deferred her admission to medical school to pursue filmmaking. “When we heard that they had been banned, we were crushed.”

Blockman, Decker, and a cast of Princetonians filmed the movie “guerilla-style” on campus and elsewhere, dodging the potential repercussions of public nudity. Directors provided a scenario for each scene but few lines, calling on cast members to invent their own. “The things that they came up with were so much more hilarious than anything that I could have written,” said Decker, who works for a production company in New York City. Improvisation spawned scores of outtakes, and the directors whittled about 30 hours of footage to 30 minutes for the final cut.

The Reunions screening received favorable reviews from seniors and young alumni, who made up most of the audience. “I thought it was great,” said Juan Lessing ’05. “It really reflects the creativity of Princeton students.” Some older alumni were on the fence. Dan Ungar ’74 said the humor was sophomoric, but admitted, “It’s more or less what I expected.”

At the end of Naked Princeton, the nudists prevail. Students

walk the hallways clad in nothing more than sneakers and backpacks, and

even professors ditch their tweeds to join the revolution. But administrators

fearing a nudist takeover at Old Nassau can rest easy: The final scenes

were filmed at MIT. ![]()

By B.T. and Jordan Paul Amadio ’05

(Steven Veach) |

Opportunity costs

Ending affirmative action in admission to elite universities would have

a dramatic effect on the number of African-American and Hispanic students

accepted, according to a study by sociology professor Thomas Espenshade

*72 and researcher Chang Chung published in the June issue of Social

Science Quarterly. A race-blind admission simulation using data from

three top universities showed that the acceptance rate for African-American

applicants would likely drop from 33.7 percent to 12.2 percent, and the

rate for Hispanic applicants would likely drop from 26.8 percent to 12.9

percent. Asian students would be the biggest winners, with their acceptance

rate projected to rise from 17.6 percent to 23.4 percent. White applicants

would experience little benefit from removing the consideration of race

from admissions: Their rate of acceptance was expected to rise from 23.8

percent to 24.3 percent. The paper is available online at http://opr.princeton.edu/faculty/Tje/EspenshadeSSQPtII.pdf.

![]()

(courtesy MSGT Timothy Ross, Army ROTC program) |

Newly commissioned

Retired Coast Guard Capt. Brad Niesen administers the oath of office

to his daughter, 2nd Lt. Rebeccah Niesen ’05, a member of the Army

Reserve, during the commissioning ceremony after Commencement. Eleven

officers were commissioned: seven by the Army, three by the Air Force

and one by the Marines. Seated are, from left, Marine Corps Lt. Susan

Debow; Air Force Col. Thomas McCarthy; and Janet Dickerson, vice president

of campus life. ![]()

The Alumni Council named three people to receive its Award for Service to Princeton: DON M. BETTERTON h’60, director of undergraduate financial aid, for his leadership in developing the University’s student aid programs and his work with alumni groups; DANIEL P. LOPRESTI *87, co-director of the Lehigh Pattern Recognition Research lab, for his extensive involvement in graduate alumni activities; and CARL R. YUDELL ’75, for his work with the Princeton Club of Chicago and for chairing four major Reunions for the Class of 1975.

Princeton ecologist SIMON LEVIN has won the 2005 Kyoto Prize for lifetime achievement in basic sciences. GEORGE HEILMEIER *62, chairman emeritus of Telcordia Technologies, is the winner in the advanced technology category. Each winner receives a cash prize of about $460,000. “In proposing many methods of biological conservation and ecosystem management, Professor Levin has made fundamental contributions to environmental science,” according to the Inamori Foundation of Japan, which presents the awards. Levin is the George M. Moffett Professor of Biology. Heilmeier was honored for his research involving liquid crystals, which are now found on devices such as laptop computers, mobile phones, and home appliances.

In its second year, the PRINCETON PRIZE IN RACE RELATIONS expanded from two cities to five, rewarding eight high school students for their efforts “to promote harmony, understanding, and respect among people of different races.” The recipients were Tatiana Maria Fernández and Mark Fitzgerald in Boston; Sarah Khasawinah and Evan Wright in Washington; Claudia Caycho and Britni Stinson in Atlanta; Brittany Royal in Houston; and Paul Nauert in St. Louis. Individual winners received $1,000, while co-winners received $500. The Princeton Prize, which is administered by alumni volunteers, is set to add Chicago, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and San Francisco to its list of participating cities in 2005—06.

Alumni are playing a central role in the revival of The Belle’s Stratagem, a comedy by a once-forgotten English female playwright that runs July 27 through Oct. 29 at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. The playwright, Hannah Cowley, was one of several featured in MELINDA FINBERG *01’s dissertation and subsequent published anthology, Eighteenth-Century Women Dramatists. Michael Cadden, director of Princeton’s Program in Theater and Dance, passed Finberg’s manuscript on to DAVIS McCALLUM ’97, a young director. McCallum directed a reading in 2003 of The Belle’s Stratagem in New York, sponsored by the Juggernaut Theater (directed by Gwynn MacDonald ’87); the response led McCallum to direct a critically praised production of the play later that year by the Prospect Theater Co., founded by four Princeton alumni. Described by Cadden as “an 18th-century version of Sex and the City,” the play will receive a full production in Oregon. McCallum will again direct, and Finberg is serving as dramaturge.

ANDREW WILES, the Eugene Higgins Professor of Mathematics, will receive the $1 million Shaw Prize in Mathematical Sciences, administered by the Shaw Foundation of Hong Kong. A Princeton faculty member since 1982, Wiles is being recognized for his 1994 solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem.

The NASSAU LITERARY REVIEW is seeking submissions of

prose, poetry, nonfiction, and drama for a fall/winter issue featuring

the work of Princeton alumni. All judging is done anonymously. E-mail

submissions are preferred at nasslit@

princeton.edu. Manuscripts can be sent to the Nassau Literary

Review, 48 University Place, Room 004, Princeton, N.J. 08544; they

will not be returned to the author. The deadline is Sept. 1. ![]()

MARIANNE WATERBURY, associate dean of students and a

friend to many alumni, died of cancer May 27 in Stockton, N.J. She was

63. Waterbury came to Princeton in 1983 as an admission officer, and moved

to the Office of the Dean of Students in 1989. ![]()