|

|

September 14, 2005: Features

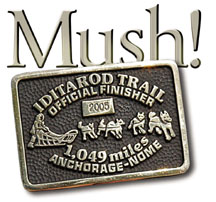

This page, Debbie Moderow ’77 on the trail of the 2005 Iditarod. Opposite page, the belt buckle given as a coveted prize to all 2005 Iditarod finishers. Though the 2005 trail was 1,161 miles long, the buckle refers to 1,049 miles to mark Alaska’s status as the 49th state. ( © 2005 Jeff Schultz/AlaskaStock.com)

Moderow and her husband, Mark, check on their dogs near their cabin in Denali, Alaska, the base for the team’s serious training. (Charles Mason/Black Star) |

For Debbie Moderow ’77, there’s no place like Nome

By Mark F. Bernstein ’83

(Photo:

Charles Mason/Black Star)

To see far, that is one thing; to go there, that is another.

— Constantin Brancusi

There’s no time for irony when it’s pitch-black and 10 below zero outside; when you’re bleary from lack of sleep and aching from anxiety and an intestinal bug; when you’re stuck out on the Bering Sea ice — frozen ocean — and your dog team, the huskies you have loved and trained and bonded with, who have spent 11 days pulling you over mountains and across tundra, have decided to park themselves on their furry little tails and go on strike. Less than 150 miles from the finish line of the Iditarod, the 1,100-mile trek across Alaska that bills itself as “The Last Great Race on Earth,” a budding canine mutiny drives all other thoughts from a musher’s head. So, stuck out on the ice, Debbie Moderow ’77 would not have recalled the prophetic quote by Brancusi that she chose for the Nassau Herald 28 years ago.

That Moderow was out there at all was unusual. Not many women take up long-distance dogsled racing in their late 40s; fewer still make it a family project. But the Moderows are a mushing family: Three of its four members have finished the race, and daughter Hannah, 20, hopes to run in 2007. Debbie Moderow entered the Iditarod at the urging of her son, Andy, 22, whose first words after finishing in 2001 were, “Mom, you’ve got to do this!” Facing the prospect of an empty nest — the Bering Sea ice of the soul, if you will — she took him up on it.

The Iditarod, perhaps the most extreme of extreme sports, commemorates the heroic 1925 relay across Alaska to deliver diphtheria serum to Nome. Racers and their teams now begin in Anchorage and traverse tundra, forests, frozen riverbeds, mountain passes, and several stretches along the sea ice when they reach the coast. Provisions are shipped beforehand to 22 checkpoints, ranging in size from the abandoned gold-mining camp at Ophir to the Native village of Unalakleet, population 882. Mushers eat and sleep on the trail (often zipped into their sleds for the night) and, other than medical checkups, receive no assistance or resupply along the route. If a sled runner breaks or a dog team quits, its musher is out of luck.

Two years after her son’s challenge, Moderow set off on the race to Nome, only to watch her dogs balk as soon as they crossed onto the ice of Norton Bay, 960 miles from Anchorage and 170 miles from the finish. Something about the vast emptiness of the place — the light, the smell, the roaring wind — had spooked them. Ears flat, eyes blank, they would go no further, and Moderow had to scratch. The following year it was her husband Mark’s chance to race, so Debbie waited until she could try again last March. Again, all went smoothly until she hit the sea ice.

This time, in the predawn darkness, Moderow tried every trick she knew to get the dogs moving. She switched them into different positions on the line to see if someone else wanted to lead. She sang to them. She scolded them. She made them howl — anything to restore their confidence.

“I’d say, ‘Good dogs! Good dogs! It’s no big deal! We’re past the bad part! Another 10 miles and we’ll be back in the woods! Ready? Ready? Hike!’ And nothing.”

As a last resort, she mushed back to Koyuk, one checkpoint past the site of her 2003 mutiny, and dropped four dogs from her team — the ones whose body language convinced her that they had instigated the mutiny, including Kanga, “the most talented dog I will ever run.” She moved new dogs, yellow Sydney and little Juliet, an almost frail-looking gray husky, into the lead. Juliet jumped up, ready to go. With another team ahead in the distance — something to break up the haunting visual expanse — Moderow’s lightened team roared off across the ice and kept going through the next checkpoint at Elim, 48 miles away. When they crossed back onto the sea ice the next day, the team again sat down, but a fisherman from a nearby village roared past on a snow machine, the dogs followed, and the crisis was averted.

After Moderow crossed the finish line, she spied Martin Buser, a four-time champion and a close friend who had counseled her after her aborted race in 2003. “I can’t believe it!” she complained about her dogs. “They still hate the coast!”

“Debbie, you hate the coast,” Buser replied. “You may not think you hate it, but they know.”

The connection between musher and dog is by nature unspoken, but enthusiasm and confidence, as well as fear and uncertainty, are communicated on both sides of the sled. Mushers speak of their dogs as partners, their relationship built on respect and nurturing. It’s all in the mood you strike, the trust you impart, and the example you set.

Debbie Moderow’s role models for adventure were her parents. Her father, Lewis Clarke ’34, was an Army cavalry officer and Wall Street lawyer who took Debbie on trips to Wyoming dude ranches and Princeton football games. In the fall, she would tag along with her father, older brother Peter Clarke ’63, and the family’s English setters as they hunted woodcock and grouse. “I didn’t care about hunting, but I loved to watch the dogs work,” Moderow recalls.

Her mother, Doris, was a pilot, encouraged by her own father, one of the early aviation pioneers who during the 1920s flew himself to work in a primitive helicopter-like contraption called an “autogyro.” Doris Clarke flew constantly, once, according to family legend, terrorizing her flight instructor by flying under the Brooklyn Bridge. During the summers she would fly a float plane down the Long Island coast, land on the beach when she saw an ice cream stand, then ask awed bathers to help her push the plane back into the surf so she could take off again.

“My mother thought the women’s movement was not necessary,” Moderow recalls. “She was born and raised saying, ‘Be who you want to be’, so she did. She didn’t exercise a lot of empathy for the plight of women with less opportunity than she had.”

Moderow, a slight woman with sandy hair, was an avid athlete at Miss Porter’s School in Greenwich, Conn., but put athletics aside during her years at Princeton, where she majored in art history. Following graduation and a brief stint in New York as a paralegal, she went to Wyoming to work for a conservation group. A friend invited her to go mountain climbing in Alaska, where she met Anchorage lawyer Mark Moderow, whom she married not long thereafter.

The mushing hobby started several years later, when Hannah returned from preschool one day and announced that a friend’s father, a musher named Bernie Willis, was racing in the Iditarod. Moderow was intrigued. She became friendly with the Willises, who, at Christmas, gave the Moderows their first dog, Salt, an 8-year-old husky who had just run in the race. Moderow learned more about mushing and occasionally would take Salt and a few borrowed dogs on short runs, her children riding in the sled basket, before dropping them off at school.

A few years later, Mark came home one night and announced that he had entered both children in a dogsled race to be run the next morning. Hannah was too short to see over the sled’s handlebar, but the children raced nonetheless. Soon the family kennel of three dogs became five, and five grew to be 10. Throughout their school years, Andy and Hannah would enter short sprint races on Saturday afternoons while their mother, the acknowledged “Type A of the family,” would take the same dogs in longer adult races on Sundays. In between there would be camping trips, with the dogs pulling the gear and the family trudging behind.

“There was a very direct and certain correlation between how tied the dogs were to Andy and Hannah at the starting line of these little races and how much fun they all had together,” Moderow recalls. “So they learned instantly that what you give an animal, you get back.”

The schedule of a mushing family is as crowded as that of a family where the kids play soccer or take ballet. In 1998, when Andy was 14, he ran the 138-mile Junior Iditarod, and the following week the Moderows packed up children and dogs and drove 1,100 miles to Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, where Hannah competed in the Arctic Winter Games. The following year, when both children entered the Junior Iditarod, the Moderows needed two teams of dogs and their kennel grew to 20. Along the way, they built a large wooden cabin in a subdivision near Denali, down the street from several Iditarod champions, where most of their serious training is done. The dogs spend their non-racing time tethered in a broad circle in the yard, often perched on top of their straw-filled huts, waiting impatiently to be hitched again to a sled. In the morning, Moderow wakes visitors by leaning out her bedroom window and calling to the team, setting off a raucous 35-dog howl that would warm Jack London’s heart.

“The whole sport for us is completely family-oriented,” Moderow says. “We all learned from each other.” Each of them filled a role, often acting as another’s handler. Mark Moderow was the logician, planning their trips and organizing the gear. Andy had the unfailingly cheerful temperament. Hannah had a special touch with the younger dogs. And Debbie Moderow became the dog psychologist, learning by reading, experience, and word of mouth how to build the trust needed to meld a team.

At the start of Andy’s senior year of high school, he went to live with Martin Buser in Big Lake, Alaska, about 60 miles from Anchorage, to train a second team of Buser’s dogs to run in the 2001 Iditarod. Working with the dogs up to 14 hours a day and attending school only one day a week in the months leading up to the race, not only did Andy finish the Iditarod (Moderow, who could not go on the trail with him, says she tracked his progress on the Internet — “I was the most nervous mother there has ever been”), but in his joy at the finish line Moderow’s own Iditarod dream was born.

“Before Andy crossed that finish line, I had never, ever, in my quietest, most contemplative moments considered running the Iditarod myself,” Moderow insists. But with her son’s encouragement, the impossible came to seem more possible. “I was born and raised in this go-for-it atmosphere,” she explains, “and [it just seemed] an opportunity I couldn’t pass up.”

Still, it costs up to $30,000 a year to feed, house, and equip a kennel of so many dogs for the Iditarod — a significant financial commitment for Moderow, who works part-time as a sales representative, and her husband. When Moderow began to train in earnest for the 2003 Iditarod, she was hampered by an unusual Alaskan autumn that had so little snow that she had to train by having the dogs pull a wheeled cart over dirt roads. To build her stamina, she worked with a personal trainer. (“It was unfair for me to be on the sled if I wasn’t in good physical condition,” she says. “I owed it to the dogs.”) To build the dogs’ stamina, she took them on four-hour, 30-mile runs, dividing the 35-dog kennel into teams of 10, trying to winnow the kennel down to the 16 dogs that would comprise her racing team. By race time, each dog had already run 2,500 miles that season.

Building mental stamina was even more important — training the dogs so they knew what to expect and could become comfortable in a routine. “The dogs need to trust you and you cannot break that trust,” Moderow says. That is done, explains Karin Schmidt, a veterinarian and Iditarod finisher, by exposing them to difficult terrain and weather conditions. When conditions get tough, Schmidt says, the dogs must understand who is the boss.

There are many misconceptions about the sport “outside,” as Alaskans refer to the lower 48 states, probably the greatest of which concerns the treatment of the dogs, who are natural runners and are treated very well. During rest stops, Moderow would massage their sore muscles; she occasionally has used acupuncture at home. Each dog received a full blood workup and an EKG before the Iditarod, and veterinarians examined each one at every checkpoint — closer medical attention, in fact, than the mushers themselves received. If the trail was rough, the dogs were fitted with booties to protect their paws. Whips are forbidden and would not be effective, anyway. How, the Moderows ask rhetorically, can you force a dog to pull a sled 1,100 miles?

Moderow learned a lesson in perseverance and faith last winter during a 300-mile Iditarod qualifying race, guiding her team through temperatures that sank to 50-below as winds howled at up to 70 miles per hour. She recalls spending one night trying to sleep on the floor of a gas station that served as a checkpoint. The cold and icy conditions had forced almost a third of the field to withdraw and Moderow, who was badly bruised from several crashes, considered quitting herself, though it would have ruined her chance at the Iditarod. Unable to rest, she told Hannah, who was there as her handler, “I’m going outside and if those dogs aren’t enjoying this more than I am, I’m going to quit.”

In the frigid night air, Moderow found her dogs sleeping in the snow, as they always do on the trail. As soon as they heard her, they jumped up, barking and tails wagging.

“Mom, you’re going to finish the race, aren’t you?” Hannah asked, posing a question that answered itself.

Moderow finally set off on the 2005 Iditarod last March. Trying to stick to a schedule of six to eight hours racing and an equal time resting, mushers ran throughout the long Alaskan nights, wearing headlamps and hanging lights from their lead dogs’ collars to light the way. In addition to her problems on the sea ice, Moderow suffered from an intestinal flu for several days but never considered dropping out. “After they say ‘Go,’ you’re going to deal with whatever you get with whatever you’ve got,” she says of the Iditarod ethos.

On the last morning, as her husband and children waited for her, Moderow and her huskies roared off the last section of sea ice and down Nome’s Main Street toward the finish line. “I just said, ‘Straight ahead!’ and they went right down the middle of that road,” she recalls. “The dogs were so excited and I was so excited. When I heard that siren go off [alerting those in Nome that a team is nearing the finish line], I said to them, ‘You guys, this is for you!’” She finished in 13 days, 19 hours, 10 minutes, and 32 seconds, good for 56th place among 79 entrants, and 11th of the 15 women mushers.

Having met the Iditarod challenge, Moderow does not see herself trying the Last Great Race again. But lately, she admits, she has started to think about entering the 1,000-mile Yukon Quest, which bills itself as the “toughest sled-dog race in the world” because of the steep summits and relatively small number of checkpoints. “I’m about to turn 50,” she says a bit sheepishly, “and I need a goal.”

One goal is already set: to continue training the dogs so that Hannah, now a Cornell senior, can run them in the 2007 Iditarod. Hannah sounds ready to go. “Seeing my dad and brother finish the Iditarod was one thing,” she says. “But seeing my mom do it made me really want to go myself.”

If so, she would not only continue a family tradition, but would make a bit of history. The Moderows would become the first complete family to finish the race, and Debbie and Hannah the only mother-daughter team.

“My mother never told me to do crazy things,” Hannah adds.

“But she was the role model.” ![]()

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.