|

|

October 5, 2005: Features

|

Is

Michael Eric Dyson *93 right?

Taking on the class divide in America’s black community

By Katharine Greider ’88

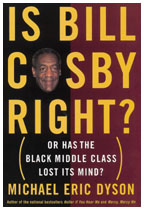

On an infernally hot July day in midtown Manhattan, University of Pennsylvania professor Michael Eric Dyson *93 was winding up a 14-city tour promoting his new book, Is Bill Cosby Right? Or Has the Black Middle Class Lost Its Mind? For weeks Dyson had dogged the steps of the avuncular and celebrated Cosby, himself on a “call-out” tour to elaborate on a 2004 speech in which he urged poor black people to look to their own materialism, lax parenting, and disdain for learning as explanations for their stalled progress. Dyson had mounted a passionate defense of the black poor from whom he emerged, and in the process put his own name up in lights, if not for the first time, then perhaps with the brightest wattage yet. He came to Bryant Park a high-profile intellectual with another best-selling book.

As he stood there amid the sycamores and kiosks, the New York Public Library in all its Beaux-Arts glory as his backdrop, there was an air of inevitability about it all. Imagine a kid from the Detroit ghetto dreaming of the Left Bank and picking his way through Being and Nothingness (in the original French). Consider Dyson at 21, a college freshman at last, testing his oratorical skills and spiritual breadth by preaching at black churches in Tennessee. Picture him a Princeton doctoral candidate in religion, meeting weekly with Professor Jeffrey Stout *76 to read and discuss pages of critical argumentation — and then incensing his mentor by whipping out a complete draft of his dissertation at the very meeting in which the prospectus was approved. “His work was good, don’t get me wrong,” recalls Stout. But “Mike has potentialities that a longer process of revising might have helped him discover.” Dyson was in a hurry.

And the impediments he met along the way? Mere twists in the plot. At the boarding school to which the teenaged Dyson had won a scholarship, some white students left a note for him: “Nigger, go home.” But that July day in Bryant Park, they seemed little more than petty villains, bit players in a drama starring Dyson. Not that his response was entirely constructive. Booted from school for bad behavior and poor grades, he soon fathered a child he was in no position to support, the aftermath of which was a few years living on welfare and the scroungings from odd jobs, as well as a hasty marriage and divorce from a wife who deemed him “pathetic.” Yet even this trouble — the kind, Dyson has pointed out, that might get a person labeled a “typical, pathological, self-defeating young black male” — could, on the final day of his latest book tour, be seen as character development, a kind of dark night of the soul that only increased the loft of his ultimate trajectory.

In short, now that Dyson was a well-heeled intellectual, Penn’s Avalon Foundation Professor in the Humanities and African-American Studies, it seemed deeply correct that some force (one located in his own breast, maybe) should have carried him out of poverty. And from there it wouldn’t be much of a stretch to conclude that Cosby was right, that others were left behind in large part because they were, in their behavior, in their values and aspirations, to quote the popular phrase, “so ghetto.”

But it was precisely to slash at this orderly moral canvas that Dyson carried his rhetorical ax to Bryant Park. A “vicious reductionism,” he calls it, that harshly illumines promiscuous mothers and men with “pants down around the crack” (Cosby) while neglecting the structural forces that confront poor black people — say, lousy underfunded schools and the disappearance of jobs from the postindustrial urban center. In Cosby, Dyson finds the articulation of an uneasy mix of “racial uplift” and embarrassed put-downs of poor African-Americans that he claims has run through the “Afristocracy” since the post-Emancipation era.

“Some of it is ignorance, some of it is willful ignorance,” he told his mostly African-American New York audience. “Some of us just don’t want to know. Right? This is my group. I’m in my club. I am healthy. Wealthy. And wise. I made it on my own, that’s on y’all. You would think that most black folk, most poor black folk, most Latinos, most Asian brothers and sisters or Native Americans or poor white brothers and sisters — those of us who have struggled — would know how to reach out and be empathetic.

“I understand Mr. Cosby’s tired and sometimes you get tired. I mean, let’s be honest, a lot of people done said what Cosby said in the privacy of their crib: ‘Damn, these Negroes, my God!’ And you talkin’ about your mama” — here Dyson got a big laugh — “‘My God!’ Then you calm down, stop being so self-serious. You ain’t the savior of the world, and you realize that the people you trying to get at, you mad at — don’t get mad at them, get mad with them.” And now his tone grew serious. “Because their backs are against the wall.”

While many have received Cosby’s remarks as refreshing and principled truth-telling, Dyson insists that, at its worst, the speech reproduced ugly stereotypes, and in its better impulses was nothing black people haven’t been saying and hearing for years in church, in barbershops, on the street corner – and, one might add, in rap lyrics, on the Internet, and in the Ivy League. This conversation takes in questions about what it means to be black in America, about class identity, about why black people are disproportionately poor, and what to do about it and who should do it. It explores what it means to speak a stigmatized vernacular, the everyday uses and misuses of the “n-word” (which has evolved into an edgy term of endearment in some African-American circles), and the positive and negative aspects of hip-hop, not to mention its relation to a global audience that both despises and glamorizes the poor black communities that created it. For starters.

It’s a discussion in which Dyson figures prominently. A frequent lecturer, Baptist preacher, journalist, and author of popular books on subjects from Martin Luther King Jr., to rapper Tupac Shakur, the 46-year-old Dyson is seen by many as the heir apparent to such black intellectual luminaries as Princeton’s Cornel West *80 and Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates Jr. Fans distinguish him as the “hip-hop intellectual,” shorthand for his ties to the working class, the young, and the current cultural moment. “For me, Dyson made the life of the mind sexy,” says Mark Anthony Neal, an associate professor of black popular culture at Duke University who fell for Dyson’s work more than a decade ago as a student embarking on his graduate career at the University of Buffalo. In light of Dyson’s Ivy League pedigree, some are inclined to see his down-with-the-people stance as performance, says Neal, “but I think this is genuinely who he is. By 18, 19, he was a father on welfare. He’s just carried that stuff with him as he’s gone up through the ranks. ... Part of why he responded so quickly and so forcefully to Cosby is, indeed, he took it personally.”

In his Cosby book, Dyson uses history and social science to raise nuanced images of poor black people; he portrays the larger culture’s location of vice in the black ghetto as a classic projection in which all things despised or problematic are externalized and dumped on the vulnerable. In response to Cosby’s acerbic take on invented black names like “Shaniqua” and “Taliqua,” Dyson contrasts African-Americans’ exuberant naming practices with the long historical moment when white folk enslaved them, took away their names, and mocked them with classical names like “Socrates” or debased them with monikers befitting barnyard animals. He talks about how the practice of giving a baby a name that describes the occasion of his or her birth, a particular day or mood or wish, stems from Africa. “We don’t think it’s funny that a white kid would be named Brandy,” Dyson remarks, “but it’s quite ridiculous for a black person to name a kid Chardonnay.” And then again, he says, most people manage to get their minds around Shaquille, Condoleezza, and Oprah. By any other name, argues Dyson, a poor black Shaniqua would face the same scorn — and the same obstacle course of educational and economic barriers.

In the shade of Bryant Park, Dyson made the case that poor black people are no more degenerate than others, citing figures as diverse as heiress Paris Hilton (of sex-tapes fame) and Clarence Thomas (whose “hustle” is “quite complex”). Afterward, E. Reece Hopkins, known as radio personality Crossover Negro Reece of the syndicated Star & Buc Wild radio show, had this to say to him: “I can’t see how you can sit here and make excuses for people who need to step up to the plate and knock it off with the ignorant language, ignorant acting.” How, he asked, could Dyson endorse gangsta rappers who call women “bitches,” glorify violence, and sometimes die by it? Then Peggy Durant approached the microphone. “I’m part of the working poor,” she said carefully. “I work at a law firm, but that doesn’t mean anything; I’m still struggling. ... A lot of what I’m receiving from black brothers and sisters is that the youth, they don’t want to listen to what somebody like me has to say. What can I do to help them out?” And then there was Barbara Maddox. She wore a red shorts-and-T-shirt set, and her hair, graying at the temples, was drawn back to reveal a beautiful, melancholy face. “My question,” she began, “is since you and Bill Cosby got similar starts in poverty, why hast thou not forsaken us?”

The American masses tend to edify themselves on certain fine points of this intraracial conversation according to the demands of the news curve — Clarence Thomas and Anita Hill, O.J., Michael Jackson, all of whom Dyson has commented on publicly. But Dyson is not content that vivid debate among black people about black life should merely hold up the mirror, or the metaphor, for white self-understanding and cultural analysis. As he puts it, “We want to get some of that, too. We are redirecting these questions at ourselves: What does it mean for us?”

Dyson is intent on being a communicator, a bridge between the ’hood and the academy, young hip-hoppers and the battle-scarred civil rights generation. To do that he must contend with what he calls “competing schemes of authenticity,” including (but not limited to) academia’s propensity to sniff at the popular subjects he treats and hip-hop’s remonstration to “keep it real,” meaning rooted in a narrow definition of urban cool. Erik Parker, music editor for Vibe magazine, observes that Dyson’s taking hip-hop to the classroom serves the academy as much as it does hip-hoppers. “No one person and no one people can claim that hip-hop belongs to them,” he says. “If academia misses out on it, it’s missing out on a big part of American culture.” Ironically, it may also be in Dyson’s study of hip-hop’s controversial street poets that he most embodies the nettlesome discipline of academia. “I’m saying to you that life is complex and not black and white,” he told Crossover Negro Reece in answer to his outraged question. “The same Tupac [Shakur] who could express destructive, vicious, misogynistic viewpoints could also elevate a conversation with insight. The point of my books is to ... engage the complexity of the issue.”

Unlike many intellectuals, Dyson visits youth detention centers and churches; he also goes on television shows like Today, Paula Zahn Now, and The O’Reilly Factor, where he spoke recently about race and the government’s response to Hurricane Katrina. In the academic world, this celebrity is an asset, even if it’s received with some ambivalence. Among a diverse, complex African-American community represented in the mass media by a relative few, Dyson’s access is valued, but also prompts piercing inquiry about his motivations as well as the fruits of his work. It leads some to regard him with suspicion, as one of a bunch of self-promoting “market intellectuals,” one critic charges, who interpret black people to a charmed white media. On the other hand, after a recent panel discussion on African-American class divisions sponsored by the Harlem Book Fair, a young, black TV sports producer lamented that the major networks weren’t listening in. “Until we can be heard outside of these walls,” he told Dyson and the other panelists, “we’re not going to move on as a people.” Or, as Neal observes, “Part of selling the ideas is selling the people who are behind the ideas.”

To watch Dyson talk, jovially dominating the discussion in Harlem (“I’ll defer, I’ll defer to anybody”), or engaging his Bryant Park audience, collectively, individually, at length and in blistering heat — to observe the apparently equal relish with which he greeted an old friend and spoke to Crossover about getting on the air and “bringing the rhetorical fury in your face” — is to wonder whether Dyson’s willingness to enter into any conversation is as much a matter of temperament as ideology. He likes to talk, he believes in talk, and there’s no one he won’t talk to.

“I have learned to speak in many tongues,” Dyson writes in the preface to his 1996 book Between God and Gangsta Rap. In answer to Cosby’s contention that too many black kids speak poorly, he avers the importance of mastering standard English, but also offers the beauty and moral purpose of a vernacular developed in part to conceal meaning from a hostile dominant culture: “Black vernacular has added color, as Ralph Ellison said — depth, weight, sophistication, blues reality, jazz reality, and now hip-hop reality — to American vernacular. Those are virtues, not vices.” And these virtues are abundant in Dyson’s own fluent and gorgeous multilingualism. There is syncopation, repetition, call and response, variations of idiom (“if the shoe fits, wear that”); there is hilarity, grief, the sly rattle and snap of the rhetorical snare; he samples like a rapper, with scholarly footnotes. This is a skill he’s nurtured, purposefully, assiduously, since he was a small boy coming up in what the papers called the “Murder Capital of the World.”

When Dyson thinks about poor African-Americans, he reflected in a cab hurtling away from Bryant Park, he thinks about the community that gave him big love as a child and young father, the “enormous moral appeal” of his pastor and others who helped him along the way, the “defiant beauty of the vulnerable” — “without romanticizing it,” he put in quickly, “because I saw a whole bunch of other stuff, too.” Dyson has four brothers; one went to college and works with computers, another just got a job stacking bottles for Pepsi, a third manages the grocery he’s worked in since high school, and the brother just younger than he is serving a life sentence for murder. Dyson believes that this brother, Everett, is innocent, a conclusion he arrives at somewhat tortuously in an essay written as a long letter to him.

Why do things turn out the way they do? What allows one seemingly trapped young black man to batter his way through to a better destiny? Here, as if to suggest more mystery than is imagined in Cosby’s philosophy of personal responsibility — or, for that matter, in deterministic social and economic theories — Dyson turns to the language of Christianity. He speaks not only of the black middle class but of the black “blessed,” and, in his own case, of both hard work and “some extraordinary grace.” Indeed, as a “blacked-out” youth, Dyson says, he held fast to the notion, deeply planted in him by his church, that faith could remove obstacles: “I actually ... I mean, I believed it.”

These days, Dyson’s “gifts,” to use words he once

wrote of the late Johnnie Cochran, “pour forth from his golden throat.”

But nowhere is his voice more affecting than toward the end of his missive

to prisoner #212687, when, in its painful, awkward reaching out, it attenuates:

“I hope you write me back,” Dyson writes. “I’d

really like to know what you think about what I’ve said.”

![]()

Katharine Greider ’88 is a freelance writer in New York City, and the author of The Big Fix: How the Pharmaceutical Industry Rips Off Americans.