|

|

October 5, 2005: President's Page

THE ALUMNI WEEKLY PROVIDES THESE PAGES TO THE PRESIDENT

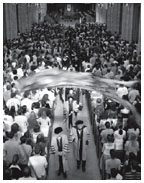

The Academic Procession leaves the University Chapel.

Honored for their outstanding academic achievements by Dean of the College Nancy Weiss Malkiel (third from left) are (left to right) George B. Wood Legacy Junior Prize co-winner Joshua Brodie ’06; Class of 1939 Princeton Scholar Award winner Catherine Kunkel ’06; Freshman First Honor Prize winner Amirali Shanechi ’08; George B. Wood Legacy Junior Prize co-winner Jessica Gasiorek ’06; and George B. Wood Legacy Sophomore Prize winner Tamara Broderick ’07. |

On September 11, I welcomed the 1,223 members of the Class of 2009, 530 matriculating graduate students, new faculty and staff, and, last but not least, a number of displaced students who are joining us from universities in hurricane-ravaged New Orleans. It was a festive day, tinged with sadness at the memory of 9/11 and the disastrous events on the Gulf Coast. As in past years, I would like to share part of my address to freshmen with you. — S.M.T.

Today marks the official beginning of the academic year. We celebrate your arrival and congratulate ourselves on exercising the good judgment to have offered you a place in the class. We also celebrate the equally good judgment you have shown in accepting our offer. You are now fledgling Princetonians, on the path to earning the right to claim that you are not just a member of the Class of 2009, but a member of the Great Class of 2009.

But what does this mean—to be a member of a class; to be a Princetonian? As a member of a class, you are here not just to learn from this place and its faculty, but from each other. And you are here not just to learn together, but to live together— to share experiences and form friendships that in many cases will last a lifetime. As a Princetonian, you suddenly will have an explosion of orange and black in your wardrobe, colors that you had relegated to Halloween costumes in the past. You will find yourself singing “Old Nassau” without the slightest self-consciousness that you are waving an imaginary hat around for half the song. A stranger who sits beside you in an airplane becomes an instant connection for a summer job when you discover that you have Princeton in common. When you leave this chapel, you will join a Pre-rade that will foreshadow the P-rade of Princeton’s annual Reunion gathering, a parade in which such august figures as our Provost Christopher Eisgruber of the Class of 1983 and Dean of the Woodrow Wilson School Anne-Marie Slaughter of the Class of 1980 can be seen marching in Reunion regalia that would, in the words of Lerner and Lowe, “make a sailor blush.” That’s one part of being a Princetonian—it is having a deep, emotional, and lifelong attachment to your alma mater, and making no bones about it!

However, becoming a Princetonian means a great deal more than costumes and songs. The goal of a Princeton education is to prepare young men and women to take up positions of leadership in the 21st century. Of course, the word “leadership” conjures up images of presidents and CEOs, but I want to stress that my idea of a leader is much broader than that. A leader is someone who has that powerful combination of determination, intellect, and strength of character to make a positive difference in the world. A leader can be a teacher who inspires students in a first-grade classroom to love learning, or a doctor who cares for the indigent, or an engineer who devises a new technology that connects remote African villages to the Web. What sets leaders apart from others is their ability to get things done, to put the needs of others before their own, and to accomplish both with a finely calibrated ethical compass.

The Princeton ideal of leadership is not for the weak of heart. It requires that you take a bold and adventuresome approach to your education, for make no mistake; this is your education to make of what you will. Princeton can be a four-year way station between adolescence and adulthood or it can be the defining years of your life, upon which you will look back and say, as so many have before you, “Princeton changed my life.” In making choices about how you spend your time, I hope you will seek out opportunities and individuals you know nothing about, and not just stay within the safe confines of your comfort zone where you excelled in high school. These four years will fly by with lightning speed, and I can assure you from my 20 years of experience at Princeton that if you show no courage now, in the spring of your senior year you will be regretting all the missed opportunities you had to explore uncharted territory.

Our expectation is that you will place more emphasis on developing lifelong habits of critical thinking than on acquiring a large body of knowledge. Both are important to have at one’s command at various times, but if you have a disciplined and curious mind, you will always find a way to acquire the information you need to move forward. Critical thinking requires an openness to the “other;” the ability and the receptivity to explore all sides of a complex question, and having done so, the self-confidence to select among the possibilities without ignoring or denigrating the positions you reject. There are issues that may be rightfully described as black or white, right or wrong, but in my experience the most interesting questions are never that straightforward, but require a subtlety and flexibility of mind that I hope you will hone over the next few years.

Beware of the ideologue with whom discussion is a shouting match. Universities and colleges cherish the right of each individual to speak freely and openly and to defend positions with dispassionate reason, not closed minds or contemptuous attitudes. There is too much empty rhetoric in the world today; this country and the world need more individuals who can navigate the complex waters around deep and fundamental questions of what it means to be human, what it means to be a citizen of a country and what it means to be a citizen of the world. We desperately need more individuals who ask questions, listen to others, absorb information, think, and then, quite possibly, change their minds.

This is one of the reasons why Princeton places such a strong emphasis on independent work—for developing critical thinking requires the continual application of your cognitive abilities to new and often difficult problems and issues. Gone are the days when you will be rewarded for dutifully memorizing and regurgitating what you have read. Here you will be asked to absorb all that is known about a subject and then come to your own conclusions about what it means.

You will be relieved to know that you will not be asked to acquire these habits alone. Throughout your years at Princeton you will be working closely with distinguished members of the faculty who are among the acknowledged leaders in their fields. They will pose questions that matter and teach you how to dig deep for the answers, beyond the material in your textbooks and the wonderful world of Google, to unearth ancient manuscripts in the recesses of Firestone Library, or learned articles in professional journals like World Politics, or DNA sequences in genetic databases. The wondrous thing about this archeological process of excavation for new information and learning is that the more you know about a subject, the more interesting it becomes. When I think back to my own university education, what remains most interesting and vivid to me are the projects that were the most challenging and on which I worked the hardest.

Of course, a Princeton education may begin in the classroom, but it certainly does not end there. It happens everywhere—in the dormitories and dining halls, on the playing fields and performance stages, and in all the places in between. There are more than 200 student organizations that will welcome you with open arms and support your aspirations: from tutoring disadvantaged children to singing beneath the beautiful arches of our campus; from prancing across the McCarter stage in an all-male kick line to making our University community more environmentally friendly. Princeton is a closely knit residential community, and much of your personal and intellectual growth will come from knowing the people in this chapel. Look around you. Somewhere in this chapel are the closest friends you will have for the rest of your lives.

Some of these friends may act and think like you; it is only natural to gravitate to people in whom we instinctively recognize ourselves. But Princeton also offers you a once-in-alifetime opportunity to connect with men and women whose lives have differed dramatically from your own; who view the world from a different vantage point. Never again will you live with a group of peers that was expressly assembled to expand your horizons and open your eyes to the fascinating richness of the human condition. After all, Dean of Admission Janet Rapelye could have saved herself and her colleagues a great deal of time and effort by admitting the first 1,223 applicants who were class valedictorians, or the first 1,223 with double 800 SAT scores, or 1,223 from the state of New York. The reason she took such care in selecting all of you—weighing your many talents, your academic and extracurricular interests, your diverse histories—was to increase the likelihood that your entire educational experience, inside and outside the classroom, is as mind-expanding as possible. When you graduate you will enter a world that is now truly global in perspective, and in which success will require that you have a cosmopolitan attitude. You must be equipped to live and work in not one culture, but in many cultures. As Tom Friedman, the New York Times columnist, wrote in his most recent book, The World Is Flat, globalization has “accidentally made Beijing, Bangalore, and Bethesda next-door neighbors.” You will be prepared to live in the new flattened world if you learn from and embrace the diverse tapestry that makes up the globe through friendships born at Princeton.

To be a Princetonian, then, is to take on the responsibilities of leadership; to take a road less traveled as thousands of men and women have done on this campus before you; to grow in ways that you cannot predict today; to change without abandoning the outstanding qualities that brought you here; and to use your talents and energies, on your own and with others, to change the world for the better. Let me conclude by paraphrasing what I said last spring at Commencement to the graduating class: “I hope you will acquire the spirit of Princeton and all that this place aspires to teach you—a determination to follow your passions in service to the common good, a respect for tradition and for progress, an openness to new ideas, the courage to stand up for your beliefs and the rights of others, a global sensibility, and a lifelong devotion to justice and freedom, all informed by the highest standards of integrity and mutual respect.” To do so, you will need to aim high and to be bold.

Good luck to you all. ![]()