|

|

January 25, 2006: Notebook

Borough OKs more space for E-Quad growth

PPPL to oversee U.S. role in new fusion reactor

A Tilghman sampler: Speaking out on public issues

Friends of the Library celebrates 75 years

A high-tech tunnel, tiny particles, and big ideas

Drawing policy lessons from Spielberg’s ‘Munich’

Gathering of conservatives hears call for new ideas

Marshall, Rhodes scholars named

Borough OKs more space for E-Quad growth

Expansion is on the horizon for the Engineering Quadrangle. In December, the Princeton Borough Council approved 100,000 square feet of additional academic and research space in the E-Quad’s zoning district. The University plans to use part of that allotment to build a home for the Princeton Institute for the Science and Technology of Materials (PRISM) near the corner of Olden Street and Prospect Avenue, according to Robert Durkee ’69, the University’s vice president and secretary.

Facilities were a key component of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences’ “strategic vision,” released in May 2004, and Durkee said that developing PRISM emerged as a top priority. The school’s most recent addition, the Friend Center, provided classroom and library space for engineering education. The PRISM building would add re-search space, providing laboratories for interdisciplinary work. No timeline for the new building has been announced.

The University had more than 82,000 square feet available to develop at the E-Quad, dating back to a 1990 zoning provision, but Durkee said the Univer-sity believed the site could accommodate more than that. In February, the University began 10 months of negotiations with zoning officials, the borough council, and residents of the neighborhood near Murray Place, adjacent to the eastern boundary of the E-Quad. “What emerged was very engaged conversation, directly between the University and the neighbors, to try to identify particular concerns that they had,” Durkee said.

The new ordinance capped the number of parking spaces at the E-Quad to limit traffic. The University also agreed that new buildings would be located at least 250 feet away from Murray Place, leaving Von Neumann Hall as the only building in the buffer zone.

In a separate but related matter, the University increased its voluntary

contribution to the borough to $1 million in 2006. It also announced a

plan to raise that payment annually by the percentage increase in the

borough tax rate, and to increase the contribution for each tax-exempt

building it constructs in the borough. The payment, given since the 1960s,

includes three components: a contribution equivalent to the local property

taxes on McCarter Theatre; a payment to the borough’s operating

budget; and a contribution for capital projects. Under prior agreements,

the University would have paid about $800,000 this year. ![]()

By B.T.

Architect’s conceptual rendering of the new ORFE building, looking east toward the E-Quad. (Office of Communications) |

The engineering school’s largest department, Operations Research and Financial Engineering (ORFE), will be moving from the E-Quad to a new home west of Olden Street.

Plans by Frederick Fisher and Partners, the Los Angeles architectural firm hired by the University, show a three-story building faced primarily with glass that would be located between Wallace Hall and Mudd Library, across from the computer science building. Fund raising is planned over the next year, with construction tentatively scheduled to start in the spring of 2007 and be completed in the summer of 2008.

“We desperately need more space overall,” said engineering dean Maria Klawe. She said the ORFE building could be built relatively quickly and inexpensively, with a price tag of $25 million, because it doesn’t require experimental labs.

Klawe praised the location for the new building, citing the engineering school’s focus on enhancing interdisciplinary research and ORFE’s “enormous amount of collaboration” with the economics department.

ORFE, which became a department in 1999, is “really unique and innovative — there are very few financial engineering programs,” Klawe said. It has grown rapidly, with 146 majors among sophomores, juniors, and seniors, and she said the engineering school is now “trying to taper off the growth.”

ORFE majors combine an engineering degree and what is essentially an applied math degree with a focus on probability and optimization theory, Klawe said. Students enter fields that include finance, information technology, management consulting, insurance, and operations planning.

The third floor of the new building is to be occupied by the newly announced Center for Information Technology Policy, headed by computer science professor Edward Felten.

The center will address social issues such as medical privacy and cybersecurity

that arise from advances in computer technology, bringing outside experts

together with students and faculty from the engineering school and the

Woodrow Wilson School.![]()

By W.R.O.

PPPL to oversee U.S. role in new fusion reactor

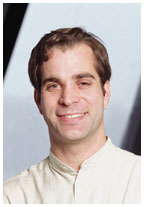

Robert Goldston *77, left, director of the Plasma Physics Laboratory, and Ned Sauthoff *75, who oversees U.S. support for a new fusion reactor in France. (Frank Wojciechowski) |

As the fusion energy world’s attention turns to a major new reactor planned for the south of France, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory will be leading U.S. participation in the project.

The five-story $5.5 billion reactor, known as ITER (Latin for “the way”), is to be built by an international consortium that includes China, Japan, South Korea, Russia, the European Union, India, and the United States.

PPPL will host the U.S. project office for ITER in partnership with the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, overseeing America’s role in providing about 9 percent of the reactor’s components and funding. The project office will be managed by Ned Sauthoff *75, principal research physicist at PPPL.

“This is a historic step in the development of fusion,” said Robert Goldston *77, director of the plasma physics lab. “We have the best team that really understands how you do these things.”

ITER, which is scheduled to begin operation by the end of 2016, is designed to serve as a bridge between current research and a prototype fusion plant that could demonstrate reliable production of electricity.

“It’s undoubted that we can make industrial quantities of fusion power,” Sauthoff said. “The big challenge is whether it will be sufficiently economical to compete. It is really an environmentally attractive energy source.” He put the odds of developing a viable fusion power plant by the year 2050 at “50–50.”

Fusion research at Princeton began 55 years ago under astrophysicist Lyman Spitzer *38, who conceived of harnessing the energy of the stars by containing hot ionized gases, or plasmas, within magnetic fields so that the plasma would not touch the walls of the reactor vessel.

Since Princeton’s Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor was shut down in 1997 after setting records for fusion performance during its 15 years of operation, PPPL research has focused on smaller, more compact devices that would require less energy and be more economical to run.

Researchers have been studying the physics principles of plasmas since 1999 as part of the National Spherical Torus Experiment (NSTX). Goldston said NSTX research made significant progress last year in controlling bulges and preventing density increases in the plasma — factors that could help a fusion plant run continuously and at lower cost.

Components have begun to arrive at the lab for another device, the $86 million National Compact Stellerator Experiment, or NCSX, which is scheduled to begin operating in 2009. What sets the NCSX apart is the computer-designed shape of its 25,000-pound vacuum vessel, which resembles a twisted donut.

Meantime, an anti-terrorism device developed by a team of PPPL researchers led by engineer Charles Gentile has been put into operation in four undisclosed locations. The device, called MINDS for “miniature integrated nuclear detection system,” can scan moving vehicles, luggage, and cargo vessels for radiological weapon materials.

The plasma physics lab, on the James Forrestal Campus in Plainsboro,

will receive about $72 million in federal funds this fiscal year and supports

more than 400 employees. ![]()

By W.R.O.

Write stuff

Writing instructors have long valued clarity over complexity. As E.B.

White wrote in his revision to The Elements of Style, “Rich,

ornate prose is hard to digest, generally unwholesome, and sometimes nauseating.”

While students may not take those words to heart, readers do, according

to a recent study by Daniel Oppenheimer, an assistant professor of psychology

and public affairs. With help from a thesaurus, Oppenheimer created similar

texts with varying levels of complexity. He then asked Stanford undergraduates

to read the texts and assess the author’s intelligence. Authors

of concise statements with shorter words were judged as more intelligent,

and authors of papers with longer, more complex words were rated as less

intelligent. Oppenheimer titled his paper “Consequences of Erudite

Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity: Problems with Using Long

Words Needlessly.” ![]()

A Tilghman sampler: Speaking out on public issues

(Illustration by David Brinley) |

In the President’s Pages (page 4–5), President Tilghman excerpts a lecture she gave last month at Oxford University. In it, she speaks about the “dangers that arise when science, politics, and religion find themselves at cross-purposes” — for example, on issues such as the space program and the raging debate over evolution and “intelligent design.” “Sending Americans to Mars may be politically astute, and promoting intelligent design in American classrooms may be a source of comfort to those who are threatened by the implications of natural selection, but neither, in my judgment, represents sound science, and to suggest that they do threatens the integrity of the entire scientific enterprise,” Tilghman said at Oxford. “The ultimate risk is that we lose the trust and respect of the public, on whom we depend for the support of science.”

The talk was the latest example of Tilghman’s ventures into the public arena to comment on issues of national importance. Since 2003, she has appeared with Microsoft chairman Bill Gates to speak about economic competitiveness, testified before the House of Representatives about the effects of immigration controls on universities, lectured on women in science, and co-chaired a committee of the National Research Council on intellectual property.

How does she choose when to speak out? “I focus on two main areas,” Tilghman explains, “one relating to Princeton and its educational mission, and one relating to my expertise and experience as a molecular biologist.” Here’s a sampling of the public talks she has given over the last few years.

Stem cell research: On Nov. 11, 2004, Tilghman gave the keynote address at the inaugural meeting of the Stem Cell Institute of New Jersey — a new institute that will conduct promising stem cell research:

At the risk of being something of a wet blanket at a coming-out party, I would like to raise two risks that I see on the horizon for stem cell research that could impede its potential for improving human health. The first, to co-opt a phrase that Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan used to describe the economic boom of the 1990s, is succumbing to irrational exuberance. I am sure that many of you in the audience have cringed in the face of newspaper or media reports extolling the promise that stem cells will cure everything from Alzheimer’s disease to halitosis. The newspapers and TV commentators did not make this up — they got their information from scientists themselves who practice a variation of irrational exuberance. Some of this comes naturally to scientists — after all, you cannot persevere in science if you do not have the frame of mind that says, “Tomorrow the experiment will work, despite good evidence to the contrary.” ... However, some of the public pronouncements in the field of stem cell research come close to over-promising at best and delusional fantasizing at worst. In either case, such pronouncements do not serve the long-term goal of developing effective treatment for diseases.

... There is a vivid precedent that illustrates the dangers of over-exuberance, namely, the field of gene therapy. The possibility that genes themselves would prove to be good therapeutic drugs was first proposed in the early 1970s, and by the early 1980s the field was in full swing. From the outset, in my view, scientists involved in gene therapy research underestimated the technical difficulties as well as the date when viable therapies would be available. They overestimated the numbers of diseases that would benefit from gene therapy, raising the expectations of suffering patients. Clinical experiments were undertaken that had no good foundation in basic research, and the experiments were so anecdotal that no reliable conclusions could be drawn. ... As of today, 25 years after the beginning of gene therapy research, the FDA has yet to approve a single protocol. ...

My other cautionary tale (or wet blanket if you prefer) is directly related to the attention that embryonic stem cells have received at the hands of politicians, pundits, and pollsters ... during the election season we have all just endured. One take-home lesson is that today’s scientists must occasionally step outside the laboratory and discuss the scientific facts that underlie policy issues with their fellow citizens. ...

The decision of the states of New Jersey and California to fund stem cell research is admirable, but even the $3 billion bond that just passed in California cannot compensate for the absence of federal dollars for research in this area. ... In the long run, we need to develop a nationwide set of policies on the use of human embryonic stem cells. Who should weigh in and who should ultimately decide this difficult and complex question? I do not have a clear answer, but of one thing I am sure: Without a political culture in which ethically charged science can be rationally discussed, the future of human embryonic stem cell research in particular and scientific progress in general in this country will be uncertain at best.

Scientists and faith: In a talk called “The Assault on Evolution” at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center academic convocation last May, Tilghman called on scientists to rise “to the defense of science”:

If the debate over the merits of evolutionary science tells us anything, it is that our work cannot be conducted in a vacuum. We must convey the nature and purpose of scientific inquiry beyond the realm of scholarly symposia, and academic articles, and we must do so respectfully, clearly, and passionately.

... We must, for starters, avoid the suggestion that science and faith are mutually exclusive — they are different manifestations of the human experience. As long as we maintain an unambiguous distinction between science and religion, neither domain should feel threatened by the other. And so, when we shout foul, as shout we must, it should always be in nuanced terms. I think that Kenneth Miller, a professor of biology at Brown University, set the right tone when he wrote, if an exponent of intelligent design “wishes to suggest that the intricacies of nature, life, and the universe reveal a world of meaning and purpose consistent with a divine intelligence, his point is philosophical, not scientific. It is a philosophical point of view, incidentally, that I share. ... [But] in the final analysis, the biochemical hypothesis of intelligent design fails not because the scientific community is closed to it but rather for the most basic of reasons — because it is overwhelmingly contradicted by the scientific evidence.”

The clarity of our public message is also critically important. ... Science need not be difficult or opaque if we choose our words and practical illustrations wisely, and the concept of evolution is no exception. Finally, we need to invest our message with passion. By passion I mean a willingness to convey the extraordinary beauty of the natural phenomena we study. We can demystify the heavens without destroying the wonder of a meteor shower. We can explain the genesis of the giraffe’s extraordinary neck or the millipede’s bounty of appendages without reducing these animals to a collection of data sets. We can call evolution what it is: a magnificent and beautifully elegant explanation for the extraordinary diversity of life that we enjoy on this planet.

Graduate education: At Vanderbilt University’s medical school on Jan. 14, 2004, Tilghman spoke about both the need for diversity in science and the need to reform graduate training in science:

Since I was a graduate student in the 1970s, the average time it takes to obtain a Ph.D. in molecular biology has expanded by two years, from four to over six years — and the length of postdoctoral training has extended at least that many years. This has resulted in young scientists who are in “training” well into their 30s, while their classmates from college are settling down, raising families, and adding to their pension plans. I have referred to this phenomenon as the “LaGuardia effect.” Students stayed longer and longer in graduate school, as they metaphorically circled LaGuardia airport, waiting for their turn to land in a job. ...

Princeton attracts some of the most talented students in the world; and of those who concentrate in molecular biology, many have the intellectual potential to become world-class scientists. Yet every year they look at their options — which are infinite — and conclude that the long and indeterminate training regimen that leads to a very difficult job market simply doesn’t stack up against their other options, where the training may be long but at least they know how long, and the job prospects are much brighter. I hasten to add that this is not about money, but about a sense of fairness in the trade-off they are being asked to make between lost incomes while they train, versus the likelihood of finding the job of their dreams.

There is no surer way to strike the death knell of science than to have a career path that discourages highly qualified students from entering the field. ...

In my own view, it is the responsibility of universities and professional

scientific societies to strike the right balance between the conduct of

research on the one hand, and the education of graduate students on the

other. This cannot be accomplished without paying close attention to trends

in the labor market. A graduate student rightfully expects to be educated

by the faculty; otherwise we should not call them students, but workers.

Graduate education must become more focused on what a student needs to

learn in order to become a scientist, and less focused on how much they

are able to produce over longer periods of time. ![]()

Friends of the Library celebrates 75 years

A gift of the Friends: The frontispiece to the first edition of Leaves of Grass, showing Walt Whitman in 1855. (Princeton University Library) |

From its inception as a small group of bibliophiles to its current membership of more than 700, the Friends of the Princeton University Library has helped provide what former chairman Robert Ruben ’55 called “the essential raw materials that scholars use.” To celebrate its 75th anniversary, the group is creating an endowment to add more of those materials to special collections, and Firestone Library is displaying some of the rare treasures contributed by the Friends.

Included in “The Lure of the Library” exhibition, at Firestone’s main gallery through April 16, are 13 single-leaf manuscripts of Emily Brontë’s poems, written in her impossibly tiny penmanship; a 1750 land survey drafted by an 18-year-old George Washington; and a Revolutionary War medal presented to Henry Lee, Class of 1773, which was purchased at auction by the Friends in 1935. At the exhibition’s opening Nov. 13, renowned collector and onetime Friends chairman William Scheide ’36 shared his recollections of Princeton’s libraries and the people who have supported their development.

With a mix of alumni, community patrons, and a few students, the Friends of the Princeton University Library is one of the nation’s largest and most active university library support groups, according to associate librarian Ben Primer. The Princeton University Library Chronicle, published three times each year, is one of just three remaining library journals. A special anniversary volume, published last fall, features 21 essays about the library’s collections, written by Princeton faculty.

In addition to publications and acquisitions, the group funds a handful

of special projects in the library, an extensive fellowship program for

visiting researchers, and a full slate of public and Friends-only events.

Its annual dinner on Jan. 28 will feature professors Paul Muldoon and

C.K. Williams as guest speakers, and the anniversary year will include

a series of talks by the curators of the library’s most notable

collections. For membership information and a complete calendar of events,

visit http://www.fpul.org.

![]()

By B.T.

A high-tech tunnel, tiny particles, and big ideas

Chris Tully *98 (Fermilab)

Studying the tiniest of particles requires remarkably large devices. The Compact Muon Solenoid device, a portion of the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland, overshadows Chris Tully *98, far right, and colleagues, from left, Andrew Baden, Robert Hirosky, and Jeremiah Mans *02. (courtesy Chris Tully *98)

|

On the outskirts of Geneva, 15 stories below the Swiss and French countryside, scientists from more than 40 countries are working to create a massive device that they hope will provide insight into the mysteries of particle physics and spark progress on a grand unified theory – the long-sought “theory of everything.”

Christopher Tully *98, an assistant professor of physics, is helping to build the timing electronics that will synchronize the experiments for the device, known as the Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Powered by superconducting electromagnetics, the LHC features a 16-mile-long ring of circular tubing. Inside the tube is a vacuum in which the LHC will collide two opposing streams of protons at an astounding rate of 40 million times per second, allowing physicists to observe the behavior of elementary particles.

When the LHC begins collecting data, Tully will work with theorists to piece together new discoveries. The device will not be operational until 2007, but it already has generated an exciting development in physics by drawing experimental particle physicists together with their theoretical counterparts in a way that Tully says would have been unlikely a decade ago. One reason: The LHC collisions, physicists predict, will generate enough energy to show evidence of the elusive “Higgs field,” a quantum field proposed by theorist Peter Higgs that many believe gives elementary particles their mass.

The Higgs field, in theory, “permeates all reality,” according to a recent Scientific American article by University of Michigan particle theorist Gordon Kane. To explain the Higgs concept, Kane uses the analogy of an ice cream vendor arriving on a beach in the summertime. The vendor represents a particle, and the beach, filled with children, is the Higgs field. As the vendor enters the beach, the children swarm toward him, slowing him down by giving him mass. Physicists at the LHC will be looking for particles called Higgs bosons, which, like the children, swarm to other particles and give them mass. In work at the Large Electron-Positron Collider (LEP), the LHC’s predecessor in Geneva, Tully and his colleagues saw “hints” of the Higgs boson’s existence, but the finding was inconclusive.

Tully, 35, has spent about half of his life working with particle accelerators. He designed one in high school and earned a $500 grant from the Virginia Academy of Science to build it. (After realizing the funding was grossly inadequate, he says, he built a plasma chamber instead.) After his freshman year at Caltech, Tully flew to Geneva as the first data was being collected at the LEP. “The thrill of that really stayed with me,” he says.

Tully worked extensively with the LEP project, living in Geneva at one point during his Ph.D. studies at Princeton. When the LEP stopped collecting data in 2000, he returned to Princeton, where he has collaborated with string theorists from the University and the Institute for Advanced Study in preparation for the LHC project.

Analyzing data from the LHC will take time, Tully says, and the stakes are high: Participating nations have sunk $3 billion into the high-tech tunnel. If the device does not live up to expectations, another collider of its kind would be an impossible sell. But the make-or-break moment also has potential for extraordinary rewards in physics, he says, including the beginnings of a grand unified theory.

“If we find this new physics, then it could be that we will rewrite

the basic description of elementary physics,” Tully says, his eyes

scanning the bookshelves in his Jadwin Hall office. “So we’ll

see. Maybe a lot of textbooks will be rewritten in the coming five years.”

![]()

By B.T.

(Abbot Genser, © Revolution Studios Distribution Company, LLC. All rights reserved.) |

The campus was the scene for two days of shooting over fall break for

“Across the Universe,” a film directed by Julie Taymor and

scheduled for release later this year. Set in the ’60s and featuring

18 Beatles songs, the film tells of a Liverpool boy who comes to America

to find his father, who turns out to be a maintenance worker at Princeton,

and befriends an undergraduate. Another film, “Annapolis,”

directed by Justin Lin, previously filmed scenes on campus and was scheduled

for release Jan. 27.![]()

When Stephanie Kingman ’08 arrived at Princeton, she found herself in a writing seminar in which every class was an hour and a half of intense discussion. At first, the premed student from Hong Kong had to force herself to speak.

School in Hong Kong was different. “We’re used to sitting in a class with 40 people, and one teacher blathers all day long,” she said. “We don’t have to say a word.”

The writing seminar taught her how to “engage in discussion,” Kingman told a dozen undergraduates who gathered at Rockefeller College in November to share the experiences and perspectives of international students at Princeton. The students, representing countries from Australia to Zimbabwe, talked about adjusting to the expectations and customs of a new land and a new campus.

One history major spoke about the jealousy with which Princeton students shield their grades from prying eyes. “One of the things I encountered was this kind of great secretive atmosphere at Princeton in terms of grades and so on,” said Iva Kleinova ’06. In the Czech Republic, she said, “Everyone was very open.”

The students said they found many American customs hard to accept. International students were surprised to find that friendly speech and first-name acquaintance in the United States masks a physical reserve.

“In Venezuela, whenever a man and a woman meet each other, they kiss each other on the cheek. Here, sometimes you don’t even shake hands — it’s just ‘hi,’” said Leon Skornicki ’06, a politics major from Venezuela.

Kingman said students are expected to have wide-ranging knowledge of U.S. culture. “They expect us to discuss things in class we don’t always know about, like American politics,” she said. If the University wanted to make foreign students feel more at home, she said, professors could be “more understanding and open to discussion” in class.

Culture shocks can be difficult, older students said, but study abroad

can create new families just when the old ones seem farthest away. They

noted that their American roommates had helped them adjust, with invitations

to family Thanksgiving celebrations. Other students were invited to a

Thanksgiving feast held by international students on campus. ![]()

By Elyse Graham ’07

Drawing policy lessons from Spielberg’s ‘Munich’

From left, former Middle East envoy Dennis Ross, Dean Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80, Foreign Policy magazine editor Moíses Naím, and “Munich” producer Kathleen Kennedy discuss Steven Spielberg’s new film and its relation to current issues. (Sameer A. Khan, courtesy of the Woodrow Wilson School) |

Munich is not your typical revenge film.

That explains in part why Woodrow Wilson School Dean Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80 chose to show Steven Spielberg’s movie — which is loosely based on Israel’s response to the brutal 1972 murder of 11 of its Olympic athletes by Palestinian terrorists — to more than 600 Princetonians, policy-makers, academics, and journalists Dec. 14 in Washington, D.C.

The film explores what happens when a free society uses undemocratic means to achieve a rough form of justice. Slaughter said Munich conveys a powerful message about America’s current war on terror, in which policy-makers openly debate whether it makes sense to ban torturing suspects or shipping them to secret overseas detention areas.

Slaughter sparked a round of applause when she said that Spielberg’s movie illustrates what a pattern of extrajudicial killings “does to a society and the individuals within a society ... we can lose the very values that we’re fighting for.”

The Wilson School co-sponsored the free, invitation-only showing with Foreign Policy magazine as part of its 75th anniversary celebration at the suggestion of Mike McCurry ’76, former spokesman for President Bill Clinton and a member of the school’s advisory council. Spielberg hired McCurry to help launch the film; McCurry promoted the movie by arranging special advance screenings featuring Dennis Ross, who served as Clinton’s Middle East negotiator.

The film’s producer, Kathleen Kennedy, and Foreign Policy editor Moisés Naím joined Slaughter and Ross for a post-screening panel discussion that analyzed what the film means for modern-day policy-makers. As Ross put it: “The choices are hard. Sometimes you pick the best of bad alternatives.”

After Kennedy defended Munich’s portrayal of Arabs in response

to criticism from an audience member, Ross noted that the exchange reflects

“what I dealt with for a long time. [The Middle East] is a conflict

where each side sees itself as the victim.” ![]()

By Juliet Eilperin ’92

Gathering of conservatives hears call for new ideas

George Will *68 (Photographs by Celene Chang ’06) |

William Rusher ’44Conservative thinkers gathered at Princeton in December to analyze the rise of conservatives in America in the past 40 years and the identity crisis they said the movement now faces.

The three-day conference at the Woodrow Wilson School, sponsored by the James Madison Program and the Center for the Study of Democratic Politics, featured a number of well-known scholars, political figures, and journalists, including former National Review publisher William Rusher ’44, former U.S. education secretary William Bennett, commentator and think-tank leader Paul Weyrich, and columnist George Will *68.

Journalist Midge Decter used the phrase “happy crisis” to describe the partnership between conservatives and Republications that, while winning control of the White House and Congress, has led to a recent stagnation in philosophies of governing.

Keynote speaker David Brooks, a New York Times columnist, called for new conservative thinking to revitalize a movement that he said has become “intellectually moribund” after years of success at the polls. “Conservatism has had this glorious rise, and is now in power,” Brooks said. “It’s in the doldrums now, but liberalism is in even worse shape.”

The reinvigoration of conservative groups reached a high point in the 1980s as Reagan Democrats converted to conservatism, speakers said. New York politician and author George Marlin said that the mainstream of the Republican Party capitalized on public dissatisfaction with what was perceived as collapse of public decency in the 1960s and 1970s. After the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision, the GOP further cemented itself to conservative social values in creating an identity based on anti-abortion and pro-morality policies, author Jeffrey Bell said.

But many of today’s conservatives are dissatisfied with the Bush administration’s failure to press for more limited government, panelists said. And many conservatives are struggling to define a new ideological mission beyond the issues — taxes, crime, and perceived liberal cultural standards – that propelled the movement into power.

Marlin highlighted what he termed leftward leanings of Republican candidates in New York, saying that the GOP risks becoming seen as “Democratic-lights” and warning of a “Democratic tsunami” in upcoming elections.

Journalist Lou Cannon and other panelists said conservatives may need to extricate themselves from the Republican Party because of disillusionment with the war in Iraq, public demand for growth in government services, and increasing class inequality.

Princeton professor Larry Bartels of the Center for the Study of Democratic

Politics said he didn’t find much consensus at the conference —

but rather, a range of views about what conservatism is, how it is faring,

and where it might lead. “I was struck by how disaffected some of

the strongest conservatives are from the Bush administration and the Republican

Congress, particularly on the issue of government spending,” Bartels

said. ![]()

By Allison Berliner ’06

(photographs by Celene Chang ’06)

“Doping

should be banned if it is unsafe, but not just because it is against the

spirit of sport. Rather, I believe it embodies the spirit of sport. ...

In one way, legalizing these drugs would level the playing field. ...

At the moment, what you have is a vast difference between the honest athletes

and the cheaters.”

“Doping

should be banned if it is unsafe, but not just because it is against the

spirit of sport. Rather, I believe it embodies the spirit of sport. ...

In one way, legalizing these drugs would level the playing field. ...

At the moment, what you have is a vast difference between the honest athletes

and the cheaters.”

“Legalizing

drugs in sports runs contrary to the essence of what makes sports and

athletes appealing in modern society. ... Think about that pact between

fans of Olympic sports who will put athletes on pedestals. We do that

because we respect the dedication and commitment of those athletes.”

“Legalizing

drugs in sports runs contrary to the essence of what makes sports and

athletes appealing in modern society. ... Think about that pact between

fans of Olympic sports who will put athletes on pedestals. We do that

because we respect the dedication and commitment of those athletes.”

Julian Savulescu, left, ethics professor at Oxford, and Craig Masback

’77, a star runner at Princeton and now CEO of USA Track & Field.

The two debated performance-enhancing drug use in sports Dec. 14 during

an event sponsored by the Center for Human Values. ![]()

Marshall, Rhodes scholars named

Jeffrey Miller ’06

Allison Bishop ’06

Yusefi Vali ’05 (photographs: John Jameson ’04; Courtesy Yusefi Vali ’05) |

Jeffrey Miller ’06 has won a Rhodes scholarship to study at Oxford, while Allison Bishop ’06 and Yusefi Vali ’05 have won Marshall scholarships to support their study at British universities.

An English major from Plano, Texas, Miller will study John Milton and other writers of the Restoration period in his first year.

Miller said he is planning a career in writing and teaching because he believes that “literature may be the one thing that saves this world from itself, and ... because I am certain it is one of the things that makes this world worth trying to save in the first place.”

He has served as co-editor-in-chief of Green Light magazine and is a member of the Human Values Forum.

Bishop, from Omaha, Neb., is a math major who is studying for a certificate in women’s studies. She plans to earn a certificate of advanced study in mathematics at Cambridge. Bishop has spent summers in research at the National Security Agency and at the University of Nebraska. A member of the Chapel Choir, Bishop hopes to become a professor and researcher.

Vali, a Near Eastern studies major from Lee’s Summit, Mo., is

in Syria on a Fulbright fellowship. He plans to study human rights and

Islam at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. His goal,

he said, is to work with humanitarian organizations to improve education

and standards of living in Islamic countries. Vali was community service

chairman of the Muslim Students Association. ![]()

Chantal Akerman, D’Est (From the East), Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/ParisThe University Art Museum is presenting “25ème écran (25th screen),” a short film by the Brussels-born experimental filmmaker CHANTAL AKERMAN, through Feb. 26. Akerman, who made her first film in 1968, began producing art installations in the 1990s, often using her own films as a point of departure. “25ème écran,” shown on a video monitor, is composed of a single tracking shot filmed along an urban street.

Kerry A. Emanuel, MIT professor of meteorology, will speak Wednesday, Feb. 1, at 4:15 p.m. at the Melvin B. Gottlieb Auditorium of the Plasma Physics Lab on the Forrestal Campus on the increasing destructiveness of TROPICAL CYCLONES over the past 30 years.

The State Department’s first ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, ROBERT A. SEIPLE, will speak Wednesday, Feb. 8, at 4:30 p.m. in Bowl 016 of Robertson Hall. His topic is “The New Alliance: The Moral Imperative Meets Realpolitic.”

ROBERT L. WOODSON SR., founder and president of the National Center

for Neighborhood Enterprise, will speak Thursday, Feb. 9, at 4:30 p.m.

on “The Underground Railroad of Self-Determination: Beyond Victimization.”

Woodson, the recipient of a MacArthur “genius” award, has

worked with youth intervention and violence prevention programs since

the 1960s. The location of the lecture was not announced as of last month;

please call 609-258-5107 for details. ![]()

Edmund Ludwig King, a 19th-century Spanish literature scholar and a Princeton

Romances language professor from 1946 until 1982, died Dec. 25 in Laredo,

Texas. He was 91. King, the Walter S. Carpenter Jr. Professor in Language,

Literature, and Civilizations emeritus, was also an authority on the Spanish

writer Gabriel Miro, and at the time of his death was preparing two translations

of Miro for publication. ![]()

In Brief

The University has offered admission to 599 EARLY-DECISION CANDIDATES who are expected to make up 49 percent of the Class of 2010. They were selected from a pool of 2,236 applicants, up 10 percent from last year, who agreed to enroll if admitted. Of those accepted, 58 percent are men, 12 percent are international students, 24 percent are students of color, half come from public schools, and 18 percent are children of alumni.

By a narrow margin, students voted in favor of Undergraduate Student Government SUPPORT OF A LAWSUIT that seeks legal approval of same-sex marriages in New Jersey. A referendum asking if the USG should sign an amicus brief prepared by the Princeton Justice Project, a student group, was supported by 51.6 percent of the students voting. In a second question, 73 percent of students said they support the right of couples to marry, regardless of sexual orientation.

The spring semester kicks off an EXCHANGE PROGRAM between the engineering schools of Princeton and Smith College. Maria Klawe, Princeton’s dean of engineering, said that while two Smith juniors will come to Princeton, no University students volunteered for a semester at Smith, the nation’s first women’s college to create an engineering school. “It’s a new program, and it was hard to get students’ attention,” Klawe said, “but I’m optimistic for the future.”

CAMPUS CLUB ALUMNI overwhelmingly approved a plan to donate the club to the University. Anne Lester Trevisan ’86, chairwoman of the club’s alumni trustees, termed the donation “bittersweet,” saying members were saddened by the club’s closing but pleased that the donation “will perpetuate Campus Club’s role as a social and cultural facility open to Princeton students and alumni alike.” The University will assume the club’s debt and pay $75,000 to the club for alumni activities, she said.

Professors Ihor Lemischka and Thomas Shenk and research scientist Kateri Moore each received a two-year grant of about $300,000 as a New Jersey state panel awarded its first 17 grants for STEM CELL RESEARCH. A.J. Stewart Smith *66, chairman of the University Research Board, said a major focus of the molecular biology department has been “understanding the fundamental biological processes by which embryos are formed and developed,” and said the new grants would enable the scientists to take significant “next steps” in their research. University researchers are not working with human embryonic stem cells, he said.

Six masons were released after hospital treatment for burns suffered

when a leak from a propane tank caused a FLASH FIRE Dec.

22 at the construction site of a dorm at Whitman College. Police said

the fire, which was quickly extinguished, ignited as workers who detected

a leak in the propane tank pushed it out of the building. Work resumed

on the site the same day .![]()