|

March 8, 2006: Features

Edward S. Corwin (Princeton University Archives) |

Curbing the court

Professor Edward S. Corwin played a starring role in F.D.R.'s plan to pack the court

On Dec. 16, 1936, Edward S. Corwin, the McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence at Princeton University, sent a letter to U.S. Attorney General Homer Cummings. The letter appeared to solve the problem that for months had stymied Cummings and his boss, President Franklin Roosevelt: how to end Supreme Court opposition to the New Deal.

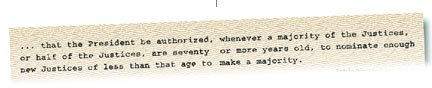

Professor Corwin’s letter (a copy of which resides in Mudd Manuscript Library) suggested that Congress empower the president to add one justice to the U.S. Supreme Court for each of the existing six justices over 70 years of age. “A 70-year age limit would secure more rapid replacement of justices,” wrote Corwin, who did not write — because it was understood — that the appointments would also make a new majority on the court sympathetic to the New Deal.

The plan’s “devilish ingenuity,” as the Los Angeles Times described it, lay not in court-packing itself, which had come up numerous times in partisan disputes in the previous century, but in the operation of Corwin’s age-based formula. The formula appeared politically neutral — just another Progressive reform. Roosevelt could claim to be solving the “problem” of old and feeble judges on the court, while stifling the court’s opposition to his agenda. Roosevelt’s “court-packing plan,” as the press dubbed it, appeared to be a political master stroke.

Three months after sending his letter, on March 17, 1937, Corwin was sitting at the table before the Senate Judiciary Committee, testifying in support of the plan as the administration’s lead expert witness. His three-hour testimony was a disaster, however. The “bespectacled modishly dressed constitutional law professor” (The Washington Post) with the “dictatorial manner” (The Chicago Tribune) alienated everyone on the Senate Judiciary Committee, even the Democrats.

The first sign of trouble came early, when Corwin used the word “hermeneutics” to describe the Supreme Court’s recent definition of “regulate” — as in Congress’ power “to regulate Commerce,” as specified in Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution. He had meant to convey his disapproval — indeed, his contempt — for conservative, anti-New Deal justices on the Supreme Court. “Hermeneutics,” a silly-sounding word if ever there was one, is used to describe jejune scholarship in the Dark Ages, when monks in fire-lit scriptoria pored over sacred texts, rearranging letters and words, reversing their order, to discover hidden messages from God.

If the Princeton professor meant to ridicule the court’s opposition to the New Deal, he missed his mark. Instead, he came across to all the senators as stiff and condescending, even arrogant. This was someone to be taken down a peg or two, and on a bipartisan basis. Thus committee chairman Henry Ashurst of Arizona, himself a Democrat, asked Corwin, “Would you spell that word ‘hermeneutics’?” Sen. William King of Utah, another Democrat, expressed doubts that the professor could.

Princeton graduates will be pleased to learn that Corwin correctly spelled “hermeneutics.” Brushing aside the intended barb — and the suggestion that he was a pedant — Corwin tried to make light of the spelling episode. But he wasn’t successful. The senators were in no mood for levity from the professor.

At stake was the role and character of the Supreme Court. No one doubted that enlarging the court from nine to 15 justices would quash the court’s opposition to the New Deal and set a precedent that would change the balance of power among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. And why not? Roosevelt had won a landslide victory in the 1936 presidential election, and Democrats outnumbered Republicans four to one in Congress. Clearly Roosevelt had been elected to do something about the economy, which remained in the grip of the Depression and was still very sick. And he was trying. But the Constitution kept getting in the way — or at least that was what a majority of the justices on the Supreme Court said.

In a series of decisions in the mid-1930s, the court declared that many of the laws enacted as part of the New Deal were unconstitutional, dealing a blow to Roosevelt’s efforts to revive the economy. The court said that there was a division of labor among the states and national government, and the president had to respect that — emergency or no emergency. The court said there were checks and balances among the branches of the federal government, and that the president had to respect that, too.

But Roosevelt didn’t want to hear it. And here was Professor Corwin, a constitutional expert, perhaps the greatest constitutional scholar of the century, to say that Roosevelt didn’t have to, that the conservative majority on the court was out of step with the will of the people, and with the “original intent” of the framers of the Constitution. Corwin said the court was preserving the form of the Constitution at the expense of its substance. He said that “checks and balances” among the branches of government were just tools, not ends in themselves. In Corwin, the Roosevelt administration had found a highly credentialed and — they hoped — a useful advocate.

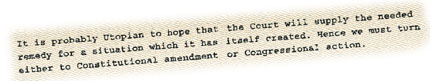

Excerpt from Professor Edward S. Corwin’s letter to U.S. Attorney General Homer Cummings, Dec. 16, 1936. A copy is at Mudd Manuscript Library.

Prior to his Senate testimony, the 59-year-old professor had been on a roll. In September 1936, Harvard University honored him at its 300th anniversary, along with Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr. Sixty-six of the world’s most renowned scholars and scientists received honorary degrees, and Corwin was one of them. Only 14 Americans wore the bronze medal with red ribbon that identified them as the special guests of Harvard University. In a letter to his mother and sister, Corwin described the trappings of his new “grandeur”: “When the police saw [the bronze medal with the red ribbon], they stopped traffic and let the wearer pass.”

Well known beyond Princeton’s halls, Corwin was a frequent writer of book reviews, letters to the editor, and articles for popular magazines and newspapers, especially The New York Times. He wrote The Constitution and What It Means Today for a popular audience; it went through four editions by 1937 and is still widely available. Informed by modern authors like Freud and Darwin, Corwin’s brand of constitutional interpretation seemed unsentimental, realistic, and entirely “scientific,” resonating with liberal opinion leaders. It didn’t hurt that Corwin followed closely in the path of his great mentor at Princeton, Woodrow Wilson 1879.

Wilson had hired Corwin in 1905 as one of the University’s first preceptors to help in the reform of the undergraduate curriculum. Both Wilson and Corwin were experts in the law, though neither graduated from law school. They were political scientists. The exciting new venture of political science called for academics to clear out the cobwebs of custom, tradition, and habit in order to fashion a “scientific” understanding of government. This was the Progressive mission, perhaps best exemplified in the academic and political career of Wilson.

But where Wilson dealt in broad strokes, Corwin focused on constitutional law. (The tradition begun by Corwin would be continued by his successors, Alpheus T. Mason, Walter F. Murphy, and Robert P. George, and would come to be known as the Princeton School.) In 1918 Corwin was appointed to the McCormick Chair of Jurisprudence, one of Princeton’s most distinguished endowed professorships and the position that Wilson himself had occupied before ascending to the presidency of Princeton. Corwin was instrumental in starting the Department of Politics at Princeton and served as its first chairman, from 1924 to 1935. In 1931 he served as president of the American Political Science Association.

Corwin was to build on Wilson’s vision of what in contemporary parlance has come to be known as “the living Constitution.” That vision called for a shift from Newtonian balance to Darwinian evolution. The notion that the federal government balanced state governments, the Senate balanced the House, the majority balanced the minority, the executive balanced the legislative branch: Such checks and balances were obsolete, said Wilson — perhaps appropriate for the preindustrial 18th century, but not for the modern industrial age. Change was the essential agent of social progress, and the Constitution had to change and evolve.

Wilson, of course, moved on to become governor of New Jersey and president of the United States. Back home, in the quiet of his library on Prospect Avenue in Princeton, Corwin filled in the details of Wilson’s grand vision. Writing in 1925 in the American Political Science Review, Corwin would call the Constitution “a living statute, palpitating with the purpose of the hour.”

So how exactly should the court turn the Constitution into “a living statute?” Corwin said the people, and the court, must recognize that the Constitution is a political document. Politicians — closest to the people — should give meaning to the open-ended expressions in the Constitution like “reasonable,” “commerce,” “necessary and proper,” “due process,” and “regulate.” In striking down New Deal legislation, said Corwin, the court was presuming to define these terms, and stepping outside its proper role.

In the short run, packing the court would bring it to what Corwin viewed as its proper role of deferring to the legislature. Beyond the short run, however, court-packing had problems. The most obvious had to do with the precedent. If Roosevelt were able to enlarge the Supreme Court to 15 justices, there was no reason his successor should not have the same power. In a short time the court could balloon into a shapeless mass, its independence and prestige destroyed.

So what was Corwin thinking? It seems likely that he thought the mere threat of packing would shock the court into seeing the error of its ways. In a 1937 Yale Law Review article that appeared one month before his Senate testimony, he expressed the hope: “We must trust the court, as we have so largely in the past, to correct its own errors.”

Debating the court-packing plan was a good way to show the Senate, and the nation, that the court was a work in progress, just like all government. Thus Corwin tried out a few new ideas on the senators. He suggested that Congress break the court into three separate sub-courts or panels, each to specialize in a different kind of case. That way, the court’s opinions would be more expert, he said, and the court could decide more cases. Or, perhaps Corwin was simply star-struck by Roosevelt, taken by being so near to the center of power. Regardless of Corwin’s reasoning, the senators viewed the plan as at best a short-term fix and at worst a power grab. Either way, Corwin had some explaining to do.

Excerpt from Professor Edward S. Corwin’s letter to U.S. Attorney General Homer Cummings, Dec. 16, 1936. A copy is at Mudd Manuscript Library.

Attempting to persuade the senators, Corwin spoke with the speed of one who has gone over the ground many times in lectures, articles, and books. The examples tumbled over one another in Corwin’s rush to convince his listeners of the correctness of his opinions and the folly of disagreement. He spoke of a “serious unbalance” in government, “resulting from the undue extension of judicial review.” The court was vetoing legislation, properly enacted by Congress, on the basis of theories that were unsupported by history and the text of the Constitution. Corwin rushed on. The very membership of the court was flawed. The justices were themselves too old and out of touch with reality. “Elderly men look backward,” said Corwin. “Their experience is inapplicable to changing conditions.”

Corwin spoke of the president’s court-packing plan as one way to provide for “a constant refreshment of knowledge of life and of new currents of thought.” Most important, the plan would put the people’s needs ahead of the “economic theories or prejudices or bias or point of view or outlook” of the majority of the present court.

His testimony swept from Locke to Blackstone; to the personal letters of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, antislavery crusader John Brown, and Abraham Baldwin, a member of Congress and the Constitutional Convention; to Federalist Papers #78, #81, and #34; and to the Convention of 1787. It was an impressive display of learning, with scarcely any room for a senator to get a word in edgewise. But Sen. King, the Utah Democrat, would try. He interrupted Corwin: “Did you know that the Federalist Party did not believe the federal government had a right to impose income taxes?”

“I did not know any such thing,” snapped Corwin, who then delivered an arcane explication of the difference between a direct tax and an apportionment. The senator from Utah was silenced, for the moment.

Corwin was not reluctant to use every date and fact at his command to support the plan. In retrospect a dash of humility and a little less learning might have worked better. The senators were powerful and proud men who had risen to their positions through careers in the law. They knew, or thought they knew, something about courts and legislatures and American history. Thus, when Corwin would say, as he did several times in technical discussions of legal principles like judicial review and stare decisis (deference to decided opinion), “That’s not true; I made a study of this subject,” his listeners were not overly impressed.

The senators were looking for clear, straight lines. Corwin was comfortable with ambiguity and, at times, even contradiction — features better suited for a seminar room. In a radio address Feb. 11, 1936, just one year before his Senate testimony, Corwin had considered and dismissed court-packing as “objectionable.” The apparent flip-flop elicited a good deal of attention from Sen. Edward R. Burke, a Democrat from Nebraska and a Harvard Law graduate: “You want us to believe now that while a little over a year ago you said the Supreme Court was large enough to properly and expeditiously handle its work ... we should place some reliance on your statement (now) when you say the court is not large enough. Is that a fact?” The answer was, well, yes: Corwin did want them to believe this, and he was manifestly annoyed that anyone would question his motives for changing his mind.

There were more problems. In his opening statement before the committee, Corwin questioned the legitimacy of judicial review, the power of the Supreme Court to review congressional legislation and declare it unconstitutional. At the very least, said Corwin, the present court should be criticized for the “undue extension of judicial review.” But in earlier times Corwin had said just the opposite. In his 1914 book, The Doctrine of Judicial Review, he concluded that the court had always had the power of judicial review, and that this tradition gave it legitimacy; he wrote that the Constitution may not spell out judicial review in plain words, but the power could still be “inferred” from the other writings and speeches of the framers.

The senators wanted to know the reason for the change in opinion. Corwin said it was a matter of fuller consideration and greater study. The senators were skeptical. Burke made a nasty aside, recalling Corwin’s earlier statements about the debilitating effects of old age. Burke suggested that since Corwin was nearly 25 years younger when he wrote The Doctrine of Judicial Review, perhaps the committee ought to believe the younger Corwin rather than the older Corwin.

Corwin threw back his own sarcasm: “Have you got anything there I wrote when I was 6 years old?”

The questioning turned to the subject of bias and prejudice — the court’s and Corwin’s. In his opening statement Corwin had said the majority of the court was inappropriately biased in favor of the economic theory of laissez-faire, and that this bias affected the court’s ruling on key New Deal legislation. The committee members returned to these words. Just exactly what did Corwin mean by “bias,” and how would he propose identifying six nominees to join the court who were not so biased?

Corwin tried to distinguish between appropriate and inappropriate bias. With this he entered a semantic quagmire where hostile listeners could easily twist his words. A bias was inappropriate, said Corwin, if it affected purely legal matters such as A’s contractual obligation to pay B, but not if extended to the political aspects of the court’s work, such as the definition of open-ended terms like “regulate” or “reasonable.” The distinction appeared to elude the senators.

Said Sen. Tom Connolly of Texas: “You have no objection to bias if it is in your way, do you?”

Replied Corwin: “These questions just indicate that what I have said just runs off your back like water off a duck’s back.”

Corwin’s testimony did not sway any senators to support the president’s court-packing plan; if anything, his testimony worked to discredit it. The Washington Post editorialized two days later that Corwin’s testimony amounted to “a frank admission” of the Roosevelt administration’s real intention: “executive control of the judiciary.” In June, the Senate Judiciary Committee issued a scathing report on the plan, which soon died.

Following his testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Corwin returned to Princeton, where he served out his distinguished career. He retired in 1946 as the McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence but continued to publish books and articles on a range of legal subjects. In 1953 the Library of Congress published The Annotated Constitution under his editorship. It is a towering achievement of scholarship and enterprise, and remains an essential reference work for lawyers and scholars. When Corwin died in 1963, his name ranked among the 10 constitutional scholars most often cited in Supreme Court decisions.

The court-packing episode had chilled the relationship between Corwin and the Roosevelt administration. There remains in the Princeton archives a short and terse letter from Attorney General Cummings to Corwin, thanking him for appearing in support of the president’s plan. That was the extent of the administration’s gratitude. In 1940, three years after his testimony in support of the court-packing plan, Corwin publicly supported Wendell Willkie for president “because I feel that the ban on a third term is a wholesome constitutional restraint.”

Corwin’s appearance before the Senate Judiciary Committee, moreover,

did not catapult him to high government office as he and his supporters

had hoped. Evidently Corwin’s name disappeared from the top of the

Justice Department’s “dope sheet of prospective court appointees”

mentioned in a letter to Corwin by a former student working in the Justice

Department. Instead, Court vacancies went to Hugo Black, William O. Douglas,

and Felix Frankfurter — men who, during the court-packing episode,

had kept their opinions to themselves. ![]()

Mark O’Brien ’73 is a preceptor in “American Constitutional Interpretation”, the course established by Edward S. Corwin in 1917. Scott Noveck ’06 and Ben Brady ’07 provided research help in the preparation of this article.