March 22, 2006: Reading Room

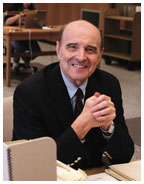

Robert L. Tignor decided to write W. Arthur Lewis’ biography after he learned that Lewis’ widow had donated his papers to Mudd Library. (Denise Applewhite) |

The

pragmatic idealist

History professor Robert L. Tignor retraces the

life of economist W. Arthur Lewis

By Alex Barnett

The late W. Arthur Lewis, a leading light in the field of development economics and the winner of the 1979 Nobel Prize in economics, was born in 1915 on the tiny, impoverished island of St. Lucia, then a colony of the British Empire. In a new biography, W. Arthur Lewis and the Birth of Development Economics, published by Princeton University Press in December, Princeton history professor Robert L. Tignor traces the extraordinary journey of his friend and colleague, who in 1963 became Princeton University’s first black full professor. He retired in 1983.

“Arthur

spent his life trying to understand questions that interest me,”

says Tignor, an expert on modern African history. “Why are some

countries so poor? How is economic development best promoted?” When

Tignor learned that Lewis’ widow had donated her husband’s

papers to Princeton, he couldn’t pass up the chance to write his

biography.

“Arthur

spent his life trying to understand questions that interest me,”

says Tignor, an expert on modern African history. “Why are some

countries so poor? How is economic development best promoted?” When

Tignor learned that Lewis’ widow had donated her husband’s

papers to Princeton, he couldn’t pass up the chance to write his

biography.

Lewis’ economic philosophy took shape after World War II, as the British Empire began to unravel and everybody — from British officials intent on reforming colonialism, to African nationalists intent on ending it — looked for ways to kick-start economic growth in the soon-to-be-ex-colonies. In a famous 1954 article, Lewis gave them a model. Poor countries, he claimed, have dual economies — part modern, part traditional — and many have virtually unlimited supplies of labor tied up in subsistence agriculture. Rapid growth was possible, Lewis argued, if cheap labor from the traditional sector was drawn into industry. “That article put development economics on the map,” says Tignor.

Many times in his career Lewis accepted invitations to advise policymakers, work he ultimately found disillusioning. Most notable was his brief tenure (1957–58) as the chief economic adviser to Ghana. This episode, almost tragic in Tignor’s retelling, offers a window into the interplay of economics and politics that led to Ghana’s collapse. Over and over Lewis gave good economic advice that Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah, ruling a fragile, newly independent state, was unwilling or unable to follow.

Throughout Tignor’s book Lewis appears as a moderate, always seeking change “from within.” He opposed racial discrimination passionately, yet he never embraced radical politics. At Princeton Lewis stirred controversy with a 1969 PAW article (to read, click here) in which he urged black college students to reject the separatist rhetoric of the American black power movement and to avoid African-American studies in favor of subjects like chemistry and law. His argument was pragmatic: A small minority in a society dominated by large corporations and institutions, American blacks would not gain power by segregating themselves.

Lewis “didn’t think race should matter so much,” says

Tignor. “He really believed we could reason our way to a better

world.” ![]()

Alex Barnett is a staff member at the Princeton University Art Museum.

BOOK SHORTS

The Courtier and the Heretic: Leibniz, Spinoza, and the Fate of God in

the Modern World — Matthew Stewart ’85 (W.W. Norton).

Stewart reinterprets the philosophical visions and relationship of two

17th-century philosophers: the reclusive Baruch de Spinoza, who believed

in a God who was identical with nature itself, and ambitious socialite

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, an orthodox Lutheran who believed in a transcendent

God. Stewart is a writer in New York City.

The Courtier and the Heretic: Leibniz, Spinoza, and the Fate of God in

the Modern World — Matthew Stewart ’85 (W.W. Norton).

Stewart reinterprets the philosophical visions and relationship of two

17th-century philosophers: the reclusive Baruch de Spinoza, who believed

in a God who was identical with nature itself, and ambitious socialite

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, an orthodox Lutheran who believed in a transcendent

God. Stewart is a writer in New York City.

The King of Kings County — Whitney Terrell ’91 (Viking).

Set in Kansas City, Mo., and opening in the 1950s, this tale blends family

saga with the history of America’s suburban development. The protagonist

watches his father — part con man, part visionary — build

a suburban empire amid the cornfields of rural Kings County and eventually

recognizes the nightmare his father helped create. Terrell is writer-in-residence

at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

The King of Kings County — Whitney Terrell ’91 (Viking).

Set in Kansas City, Mo., and opening in the 1950s, this tale blends family

saga with the history of America’s suburban development. The protagonist

watches his father — part con man, part visionary — build

a suburban empire amid the cornfields of rural Kings County and eventually

recognizes the nightmare his father helped create. Terrell is writer-in-residence

at the University of Missouri, Kansas City.

The Hoopoe’s Crown — Jacqueline Osherow *90 (BOA

Editions Ltd.). This collection of poems deals with Jewish tradition and

history. Many of Osherow’s poems concern inconsistencies and mysteries

in biblical texts and biblical prophets and poets. She writes in traditional

poetic forms (sonnet, terza rima, villanelle, sestina) and free verse

while maintaining a conversational tone that mixes humor and seriousness.

Osherow is an English professor at the University of Utah.

The Hoopoe’s Crown — Jacqueline Osherow *90 (BOA

Editions Ltd.). This collection of poems deals with Jewish tradition and

history. Many of Osherow’s poems concern inconsistencies and mysteries

in biblical texts and biblical prophets and poets. She writes in traditional

poetic forms (sonnet, terza rima, villanelle, sestina) and free verse

while maintaining a conversational tone that mixes humor and seriousness.

Osherow is an English professor at the University of Utah. ![]()

By K.F.G.

For a complete list of books received, click here.