|

June 7, 2006: Features

Farish A. Jenkins Jr. ’61 with Tiktaalik roseae, a previously unknown animal that represents the emergence of fish onto land. (E.B. Daeschler, Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia)

A reproduction of Tiktaalik remains, along with a model of what it probably looked like in real life (model by Tyler Keillor).

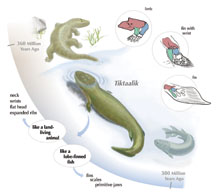

An illustration by Kalliopi Monoyios ’00 shows how Tiktaalik was a transitional species between lobe-finned fish and tetrapods.

Kalliopi Monoyios ’00 studies a model of a Tiktaalik fin she constructed. (images: from top, Beth Rooney, Kalliopi Monoyios ’00, Neil Shubin, University of Chicago)

|

Fish

out of water

Farish Jenkins ’61 uncovers a

piece in the evolutionary puzzle

By Mark. F. Bernstein ’83

In a siltstone quarry on a remote plain in the Canadian Arctic, Farish A. Jenkins Jr. ’61 and a team of scientists have uncovered the bones of the long-sought missing link between fish and land animals. Called Tiktaalik roseae, the ancient creature, which lived approximately 375 million years ago, had the body of a fish as well as bones in its fins resembling those of an arm. Scientists believe those bones enabled it to crawl out of the water and onto land.

Jenkins, the Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology at Harvard, was joined by Neil Shubin, chairman of the department of organismal biology at the University of Chicago, and Ted Daeschler of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia on a series of four expeditions to Ellesmere Island in the Canadian territory of Nunavut between 1999 and 2004. Kalliopi Monoyios ’00, a scientific illustrator working with Shubin, was the first to draw what Tiktaalik probably looked like, based on the fossil findings. The team’s discoveries were featured on the cover of the April 6 issue of Nature. “It’s a big deal,” Shubin says, describing the scientific importance of the discovery. “What we have here is a fish that has features of fish and land animals.”

Tiktaalik — the Inuit word for “large, shallow-water fish” — had scales and fins like a fish. Yet its neck and rib cage resembled those of four-legged land animals (known as tetrapods), enabling its head to swivel independently of its body. Its fins were very un-fishlike, containing structures similar to a tetrapod’s arm, with bones that flexed rather like a primitive elbow and wrist and that allowed the parts of the fin to move independently of each other, too. The scientists found several well-preserved specimens, ranging from 4 to 9 feet long.

A zoologist, Jenkins is interested in all types of animals — including man. After training at Princeton under famed geologist Glen Lowell Jepsen, he earned both a master’s degree and Ph.D. in geology and geophysics at Yale as well as a medical degree, explaining, “You need to learn anatomy to understand fossils.” He is curator of mammology and vertebrate paleontology at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and a professor of human anatomy at Harvard Medical School.

One of the Tiktaalik specimens was so large that it was impossible to excavate it in one piece, so the next step for Jenkins and his fellow researchers is to go back to the quarry and retrieve the rest of it. They also will look for other Tiktaalik specimens that might be embedded in the area and begin to search through younger layers of rock for fossils of what Tiktaalik might have evolved into next.

Many scientists view Tiktaalik as a compelling rebuttal to religious

creationists. Jenkins says the discovery inspires its own awe. “Once

you look at these things, it draws spirituality out of you,” Jenkins

says. “It’s wondrous.” ![]()

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.