|

September 27, 2006: Features

From

Ireland to Princeton

A theater renaissance comes to campus

By Brett Tomlinson

Collecting books, Leonard Milberg ’53 says, is a form of education, a chance to enjoy the beauty of language and delve into topics that may have slipped by during undergraduate days. It also can be a “disease” of sorts, he adds with a laugh — contagious and difficult to cure, “but it’s a good disease.”

For more than a decade, Princeton’s libraries have been beneficiaries of Milberg’s affliction. The 75-year-old chairman of Milberg Factors, a private commercial-financing firm in New York, started collecting books by American poets in the early 1990s, later donating them to the Princeton library in honor of his friend Richard Ludwig, professor emeritus of English and the former associate librarian for rare books. In the course of collecting, he embarked on new friendships, working closely with J. Howard Woolmer, a Pennsylvania-based rare book specialist, and speaking frequently with professor and poet Paul Muldoon.

In October, the University will unveil the Leonard L. Milberg Collection of Irish Theater, acquired in large part by Woolmer and given in honor of Muldoon. It is the fourth major book collection given by Milberg, who has donated two collections of American art as well.

To celebrate the new collection, Princeton’s library and theater communities have organized a series of events, beginning Oct. 13, including an exhibit of about 200 of the collection’s most notable pieces and a weekend theater symposium featuring Irish actors Stephen Rea, Gabriel Byrne, and Fiona Shaw and Tony award-winning director Garry Hynes. Hynes will direct the play Translations, by the prominent Irish playwright Brian Friel, at McCarter Theatre Oct. 8 through Oct. 29. After the play’s run at McCarter, it is slated to move to Broadway in January.

“And all of this is the result of a man who decided to collect books,” says Michael Cadden, director of the Program in Theater and Dance. “It’s quite a ripple effect.”

Milberg has an abiding interest in the arts, from visual pieces like those in his Early Views of American Cities collection that adorn the walls of Firestone Library, to the written works in his collections of American poets, Irish poets, and Jewish-American writers on the shelves of the rare books department. His Irish theater collection draws from his affinity for the performing arts.

The collection is one of the largest assemblages of Irish theater materials outside of Ireland, and Milberg credits Woolmer — whom he calls “a marvelous treasure hunter” — for finding most of the notable pieces. Woolmer traveled to England and Ireland three or four times a year for the last three years, working his way through rare book stores, auction houses, and several of Dublin’s most famous theaters.

Covering about 150 years of history and more than 80 playwrights, the collection ranges from the prolific 19th-century playwright Dion Boucicault to modern voices such as Friel, Marina Carr, and Martin McDonagh. Woolmer paid particular attention to the formative years of the Abbey Theatre, the Irish national theater founded by William Butler Yeats and Lady Augusta Gregory at the turn of the 20th century. The Abbey aimed to develop a repertoire of distinctly Irish plays, performed by Irish actors for Irish audiences; in just a few decades, it made remarkable progress, first through the works of Yeats and J.M. Synge, and later with plays by Sean O’Casey.

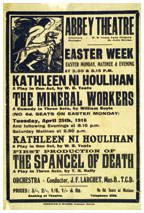

Notable finds in the collection include a book of plays, inscribed by Yeats to Gregory, that has a handwritten Yeats poem; a poster from a planned 1916 Abbey Theatre production of Yeats’ and Gregory’s Kathleen ni Houlihan (first presented in 1904) that never took place because of the 1916 Easter Rising; and a children’s play published by Jack Yeats, W.B. Yeats’ brother, complete with a miniature fold-out stage and cardboard players. The exhibition of the collection, “Players & Painted Stage,” at Firestone Library’s main and Milberg galleries through April, also includes a first edition, large-paper version of Samuel Beckett’s En Attendant Godot (Waiting for Godot), one of just 35 copies produced.

In searching for unique items from the Irish theater, Woolmer turned up two manuscripts: The Cooing of Doves, an unpublished one-act play by Sean O’Casey that was later incorporated into The Plough and the Stars, one of O’Casey’s most significant works; and a working typescript of Lady Gregory’s memoirs. The Princeton University Library Chronicle, due out in October, will feature both manuscripts. The O’Casey play will be published with notes from O’Casey biographer Christopher Murray, and a piece by the novelist Colm Tóibín will accompany excerpts from the Lady Gregory manuscript. During the Irish theater symposium in October, The Cooing of Doves will be read publicly for the first time. Cadden hopes to enlist some of the distinguished guests in lead roles.

While the collection will be the focus of October’s Irish theater weekend, the production of Translations may be its most anticipated event. Set in rural Ireland in the 1830s, the play is viewed by many as Friel’s masterpiece, examining themes of culture, language, and identity. Hynes, who recently directed the cycle of Synge’s six plays at Lincoln Center, is one of contemporary theater’s best-known directors, and Emily Mann, artistic director of McCarter Theatre, says that her “clear-eyed, penetrating” style should create a powerful performance. “She has a very muscular, strong, compassionate, but utterly unsentimental look at human beings and the world,” Mann says. “And so there will be a very clear, strong vision to this piece.”

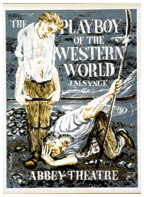

Later in the fall, theater and dance lecturer Tim Vasen and a cast of Princeton students will mount their own interpretation of another Irish masterpiece, Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World, at the Berlind Theater Nov. 10, 11, 16, and 17. Undergraduates in several classes will be studying Irish theater this semester, using the Milberg collection for research projects.

According to Yale English professor Wes Davis *02, who wrote the introductory essay for the Irish theater collection’s catalog, Milberg’s donation will be a remarkable resource for students and scholars because of the wide range of playwrights included. Some plays in the collection never made their way past regional Irish theaters, but they offer significant context for better-known plays. By reading contemporary plays, Davis says, a researcher can see how an individual writer’s work relates to that produced by the broader community of writers.

For Milberg, the ultimate value of collecting is in the scholarship

it inspires. He begins each of his collections by finding corresponding

courses in the undergraduate curriculum, to ensure that the books will

be of use. Milberg fondly recalls the words of thanks he received from

David Orr ’96, a poetry critic for The New York Times,

who studied the Milberg Collection of American Poets as an undergraduate.

“If I can reach a couple of students each year who are interested

in these things, that’s my reward,” Milberg says. “That

means more to me than anything else.” ![]()

Brett Tomlinson is an associate editor at PAW.

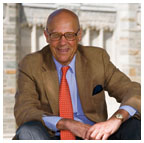

Leonard L. Milberg (Photo by Ricardo Barros)

Items displayed in the exhibition “Players & Painted Stage: The Leonard L. Milberg Collection of Irish Theater,” from top: Abbey Theatre posters for a 1916 Easter Week performance of Kathleen ni Houlihan that was canceled because of the Easter Rising, and a production, circa 1980, of The Playboy of the Western World by John Millington Synge. Bottom: a 1981 Faber and Faber edition of Translations by Brian Friel. |

A theater of their own

By Michael Cadden

Michael Cadden is director of Princeton’s Program in Theater and Dance.

The creation of the Leonard L. Milberg Collection of Irish Theater comes at a time when, to use a mot of the moment, Irish drama is “hot.” To be just a bit provincial about it, look at the 2005–2006 theater season in New York. Two of the four plays nominated for the Tony Award for best play were Irish: Martin McDonagh’s The Lieutenant of Inishmore and Conor McPherson’s Shining City. Brian Friel’s Faith Healer was nominated for best revival of a play (and won Ian McDiarmid a Tony for best featured actor in a play), while Irish scenic designer Bob Crowley carried off his third award, this time for The (very English) History Boys.

Off-Broadway saw superb revivals at two venues that regularly feature Irish drama: George Bernard Shaw’s Mrs. Warren’s Profession (winning an OBIE for actress Dana Ivey and the plaudits of my English 205 class) and John B. Keane’s The Field at the estimable Irish Repertory Theater, and Marie Jones’ A Night in November at the Irish Arts Center. This “Year of the Irish” in New York was capped off in grand style with the arrival of Galway’s Druid Theatre Company at the Lincoln Center Festival to present DruidSynge — the complete plays of John Millington Synge — in an all-day marathon.

Although New York likes to think of itself as the country’s theater capital, even more Irish plays are done outside the five boroughs. The best place to see the work of Marina Carr, Ireland’s leading female playwright, has been at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre, where both The Mai and Portia Coughlan have been staged over the last few years, along with Friel’s Wonderful Tennessee and Frank McGuinness’ translation of Sophocles’ Electra, which later moved to Broadway. The Druid Theatre Company’s Garry Hynes, the first woman to win a Tony Award for directing, will direct Friel’s Translations at McCarter next month. Elsewhere in New Jersey, Red Bank’s Two River Theatre Company celebrated the 2006 centenary of Samuel Beckett’s birth, something no New York theater did, with a staging of Waiting for Godot as the centerpiece of a Beckett Festival.

As you read this, the Pittsburgh Irish and Classical Theatre is mounting another Beckett Festival, as part of a season that covers over two centuries of work by Irish playwrights, including Richard Brinsley Sheridan, who features so regularly in anthologies of and courses on “English Stage Comedy.” Yes, Sheridan was an Irishman; indeed, the “great tradition” in “English” comedy relies heavily on writers born or bred in Ireland, including George Farquhar, William Congreve, Oliver Goldsmith, Sheridan, Oscar Wilde, and Shaw. Although these men wrote for the London stage, their sensibilities were formed elsewhere. (When Beckett was asked by a French interviewer if he were English, he famously responded, “Au contraire.”)

All four Irish winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature — W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Samuel Beckett, and Seamus Heaney — wrote or are writing for the theater; indeed, Yeats was convinced he was being rewarded for his formation of an Irish national theater rather than for his work as a poet. And it is still more often the case in Ireland than in most countries that writers primarily identified with other literary forms try their hand at writing plays, including Princeton’s own, the poet Paul Muldoon.

Now let us now recall, with an appropriate sense of astonishment and awe, that we are talking about writers from an island about half the size of Arkansas with a population, North and South, of approximately 6 million. What are they putting in the water?

It’s not the water. Modern Irish drama has its roots in a cultural project designed to address the political paralysis that seized the movement toward Irish “home rule” after the death of Charles Stewart Parnell, the “uncrowned king of Ireland,” in 1891 — a paralysis brilliantly captured in James Joyce’s Dubliners. In 1897, W.B. Yeats, Lady Augusta Gregory, and Edward Martyn met in Galway for a rainy-day conversation that soon led them to found a theater of their own. The statement they drew up that day continues to resonate to this one:

We propose to have performed in Dublin in the spring of every year certain Celtic and Irish plays, which whatever be their degree of excellence will be written with a high ambition, and so to build up a Celtic and Irish school of dramatic literature. We hope to find in Ireland an uncorrupted and imaginative audience trained to listen by its passion for oratory, and believe that our desire to bring upon the stage the deeper thoughts and emotions of Ireland will ensure for us a tolerant welcome, and that freedom to experiment which is not found in theatres in England, and without which no new movement in art and literature can succeed. We will show that Ireland is not the home of buffoonery and of easy sentiment, as it has been represented, but the home of an ancient idealism. We are confident of the support of all Irish people, who are weary of misrepresentation, in carrying out a work that is outside all the political questions that divide us.

First named the Irish Literary Theatre, this project became known in 1904 as the Abbey Theatre — now the National Theater of the Republic of Ireland.

Despite the claim that this theater would transcend politics, the Abbey was from the beginning an act of cultural nationalism. To speak of an Irish people “weary of misrepresentation” was to speak not only of the stereotypical representation of the Irish in English arts and letters as apes, drunkards, mystics, or some combination of all three; from the point of view of the Abbey’s founders, the Irish were also weary of their “misrepresentation” in the British parliamentary system, the result of the Irish Parliament’s decision in 1800 to dissolve itself and allow for direct rule from London as part of a new “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.” Making theater was a way of dreaming a new and different political entity into being, though not even these visionaries anticipated the eventual foundation of an independent republic.

Many of their audience members did, however, and acted on the political and cultural inspiration they received from nights at the Abbey. For them, the plays of what is now termed “the Irish Renaissance” directly addressed how they experienced the intersection of the personal and the political in their lives. Approaching death, Yeats queried whether one of the first plays staged by the new theater, Kathleen Ni Houlihan, which he co-authored with Gregory, was responsible for the deaths of Irish rebels during the 1916 Easter Rising: “Did that play of mine send out/Certain men the English shot?” Some rebels certainly claimed that to be the case.

What the Abbey really was, and what Irish theater remains to this day, was the focus of an ongoing conversation, as controversial now as ever it was, about what it means to be Irish — a conversation which, in many if not all instances, works for non-Irish audiences as a metaphor for what it means to be fully human: as political, social, cultural, psychological, and linguistic beings. Although the Abbey’s founders hoped their theatrical “conversational openers” would meet with a “tolerant welcome,” it’s not always what they got. The largely Catholic and largely urban audiences that rioted against Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World in 1907, for example, were in no mood to accept his “Protestant” version of the Catholic and rural west of Ireland. As far as they were concerned, the Irish were once again being misrepresented, this time by their own countryman. When Abbey audiences rioted again in 1926, this time against (the “Protestant”) Sean O’Casey’s representation of the Easter Rising in The Plough and the Stars, Yeats dressed them down with the one of the most famous of all curtain speeches (safely delivered to the papers before it was “spontaneously” delivered, to ensure the morning headlines): “You have disgraced yourselves again. First Synge and now O’Casey. Is this to be the recurring celebration of the arrival of Irish genius?” You’d have thought the Playboy riots had occurred only the previous week!

Although the rioting has subsided, we’re currently living through a second Irish Renaissance that, once again, has the theater at its center. From an American perspective, Brian Friel is often seen as the leading figure in this new landscape, because of both the sheer excellence of his plays and because so many of them (Philadelphia Here I Come!, Dancing at Lughnasa, and now Faith Healer) confirm foreign expectations of Irishness. But Irish theater practitioners never tire of celebrating the sometimes less-translatable virtues of Tom Murphy (A Whistle in the Dark, Bailegangaire, The Gigli Concert) and other Irish playwrights. They all share the knack for storytelling and the love of language so vital to the theater, as well as the fundamental belief that the best way on earth to deliver those stories is by reaching out through live actors to live audiences. The ancient Greek word for playwright was didaskalos — “teacher” — and Irish playwrights have never lost sight of their professional obligation to have something worth saying, first of all, to the audience gathered in the room before them. The local fulfillment of that fundamental theatrical contract has won them international acclaim.