|

October 11, 2006: Features

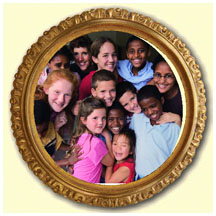

Liz Green ’84 and her 12 children, clockwise from top: Caroline (in red), Abel, Hannah, Nathanael, Emily, Susannah, Benjamin, Elizabeth, and Sarah, next to Liz. In the center, clockwise from top: are Alexander, Timothy, and Daniel. (Photographs by Forest McMullin/black star)

Liz Green ’84 instructs three of her 12 children: 12-year-old Elizabeth, 6-year-old Susannah, and 9-year-old Alexander.

On Saturday mornings, family members crowd around the breakfast table to eat pancakes prepared by Dad. Howard Green horsing around with his children Abel, on top of Howard, Nathanael, and Benjamin, at bottom. Timothy, in red-striped shirt, and Alexander also pile on top.

Working on a puzzle are, from left, Susannah, Hannah, Benjamin, Daniel, and Emily. |

Full

house

Living and learning in a family of 14

By Katherine Federici Greenwood

It’s 8:30 on a Tuesday morning, and Elizabeth Stevenson Green ’84 is sitting at her kitchen table with a cup of coffee, a few crumbs from breakfast dotting the counter. Yet this is no time for relaxation. On the wall behind her is a white board with numbers scrawled during a math lesson for three of her children, just ended. Now two other daughters — a teenager and a 6-year-old — enter the room to learn math from mom. And when that’s over, there will be lessons for others. Seven others, all Greens.

While many people have large families, and a growing number of families home-school their children, few have undertaken the task that Liz Green and her husband, Howard, have: home-schooling their 12 biological and adopted kids, ages 5 to 14, including some who are still dealing with emotional burdens and learning delays dating to the days before they arrived in the Green household.

Liz Green, a politics major at Princeton, is now mother, teacher, and principal of her own one-room schoolhouse. With the children — including two sibling groups from Ethiopia and a daughter from China — as well as a cat, 14 chickens, a rabbit, three birds, a gerbil, a guinea pig, two hamsters, a frog and some fish, Liz is in almost constant, but controlled, motion. She rarely raises her voice. At any moment, while she is helping one child with multiplication or algebra, another child is working at the computer in the family room, while another is practicing piano in the sunroom, and yet others are curled up with books or crouched under tables, doing creative-writing assignments in their journals. Four of her younger children — she calls them the “puppies” because they move in a pack around the house — get up to an hour and a half of schooling a day; the rest of the time the puppies play outside or in the garage. They are already independent: “I never go out unless I hear banging,” says Liz.

The Greens live in Jamesville, N.Y., a tiny suburb south of Syracuse. From the windows of the kitchen you can’t see any neighbors. You do see rolling hills, cornfields, and barn silos. Their modern house is big, with five bedrooms and six bathrooms — plus a guest suite in the basement — and sits back from the road on a wooded, seven-acre lot. There are not many toys — just a Darth Vader mask in the “big boys’ room,” some toy cars spread around the floor in the basement, and a few dolls in the girls’ rooms — and no electronic games or iPods. One TV is in the basement, but the children are allowed to watch only an hour-long video once a week. Books are everywhere, and at any time of day, there is at least one child immersed in a book.

Liz and Howard, an anesthesiologist at St. Joseph’s Hospital Health Center in Syracuse who spent five years as a Marine Corps helicopter pilot, met at church in August 1990, when he was a medical resident at Dartmouth and she was associate campus director of Campus Crusade for Christ. They married a year later, and planned to have four or five children. First came Caroline, who has grown into a teenager who spends her time playing piano, singing, and sewing or making her own earrings. Elizabeth, more reserved than her older sister, followed 19 months later; today the two girls, 13 and 12, help care for the other children.

Alexander, the Greens’ first son, was born in 1996; at 9, he is a talkative boy who likes helping his dad fix things around the house. Eighteen months later, Timothy arrived. Now healthy, Timothy was born with a heart defect involving the narrowing of the aorta, which could have led to potentially deadly heart damage. He had surgery to correct the condition when he was 3 days old, as his parents “sat in that waiting room and prayed,” Liz recalls. Doctors told the Greens that another child could be born with the same condition, and they began to consider adoption. But the paperwork and expense involved discouraged them, and soon Liz gave birth to a healthy fifth child, Susannah, now a bubbly and smart 6-year-old with long blond hair.

Still, the adoption idea had been planted. The thought of adopting an abandoned girl in China kept rolling around in their minds. “We kept thinking about those baby girls,” says Liz, but the prospect was a bit frightening. Would the child love them? Would she resent them for adopting her? Ultimately they decided that they would face up to the challenges, that the benefits outweighed the risks. In 2002, they adopted Emily, 15 months at the time and weighing just 13.5 pounds. Caroline traveled with her parents and her sister Elizabeth to retrieve Emily from China and started a scrapbook to document the experience. Today, it sits on a bookshelf in the room Caroline shares with three sisters, waiting for the day 5-year-old Emily turns 9, when it will be a gift.

Emily arrived from China tearful and underweight with a bacterial infection. She cried whenever Liz held her; sometimes, she screamed. “It was not easy,” Liz says, but within a few months Emily had gained weight and bonded with her mother. “She blossomed,” says Liz.

The successful adoption prompted the Greens to think about further enlarging their family, targeting children in need. Liz requested information from an agency that places children from Ethiopia in American homes. The day the packet arrived, Howard ripped it open and pointed to siblings whose parents had died of AIDS (the children do not have the disease or the HIV virus). “I gasped,” Liz recalls — there were four children pictured. The children had lived with their birth parents until their father died of AIDS. Then they moved in with an aunt and saw their mother regularly until she, too, died of the disease. Eventually, the aunt, who was too poor to care for the children, gave them to an orphanage.

The Greens’ concerns about adoption roared back. Would Liz, who had home-schooled all her biological children, be able to teach poor children with little education? Would she have the emotional resources and energy to cook, teach, and care for so many kids? Howard worried whether, despite his good salary as a doctor, he would be able to provide for such a large family. They spoke to family members, to a pastor, and decided, again, that the opportunity to “give a life to these kids” could not be wasted. Howard recalls that the decision “felt like leaping off a cliff.” But they leaped.

In November 2003, soon after the Greens completed an addition to their house, the four children arrived from Ethiopia at the Syracuse airport, tired and scared, unable to speak English: Sarah, who was 11; Hannah, 9; Abel, 6; and little Benjamin, 4. The Greens’ biological children partnered with their new siblings, teaching them the basics of American life: How to speak English. How to dress in upstate New York. How to use a water fountain.

The following year, while the Greens were still adjusting to their new family of 10 children, they learned about two other Ethiopian orphans in need of homes — and in September 2005, Liz and Howard traveled to Ethiopia to bring them back. The boys, Daniel and Nathanael, had been injured: Both had been burned and shot, Daniel in a heel and Nathanael, 8, in an arm, though the adoption agency could not explain how they were injured. Daniel, 6, had surgery to remove the bullet and infected heel bone in Ethiopia and now wears a brace; Nathanael had surgery in the United States, but the required physical therapy was so painful and traumatic that the Greens halted it. When he is older, he will require more surgery and physical therapy to regain movement in his arm, which he can barely bend.

Gradually the children found their way, though, looking back, Liz says the family was not fully prepared to deal with their new children’s emotional wounds. The last few years have been challenging, particularly for the oldest child, Sarah, who may have felt the loss of her parents most keenly. Liz suspects that Sarah worries that her new parents will one day abandon her. “There are things buried, which just need to come out,” says Liz. But Sarah recently has begun to smile and initiate conversation with her parents, and now enjoys sewing with her sisters. She has made strides in her schoolwork, particularly in math.

The Greens take pains to keep their adopted children connected to the cultures they left. The family celebrates the Chinese New Year for Emily. They cook Ethiopian food and help their Ethiopian-born children stay in touch with friends from the orphanage through e-mail. Occasionally, the Greens call the aunt who cared for Sarah and her siblings, and they get together with other families who adopted children from Ethiopia. The children will soon try to relearn their Amharic language, using a CD.

Family members speak openly about race. “We express skin color as an expression of God’s creativity,” Liz says, explaining that she tells the children: Just as there are many different kinds of flowers, there are different skin colors. In history lessons, she teaches the children about slavery and racial prejudice in the United States. You may experience these prejudices, she tells her Ethiopian kids — though so far, she says, the children have not.

The Greens’ routine begins each morning at 5:30, when Liz and her husband get up to have coffee, pray, and exercise before the children are awake. On most workdays, Howard leaves at about 7 a.m. and will be gone until 6:30 in the evening. Some days, he returns much later. He’s a hands-on father — reading bedtime stories, making Saturday-morning pancakes — but most of the daily work of child-rearing falls to Liz.

With no nanny or housekeeper to help with the work, teamwork and organization are essential. All the children have chores. Each day, the children are divided into three teams: one to clean up the clutter and do the laundry, one to take care of the kitchen, and one to care for the animals and sweep the floors. There are four children on each team, with the older daughters acting as team leaders. The laundry team does about three loads of laundry each day; after dinner, the crew sits on the floor and finishes sorting the day’s laundry before delivering baskets to the proper bedrooms. Socks, which never seem to find pairs or end up with their owners, are a big challenge.

Liz prepares dinner, but the children take care of the other meals. On a typical school day morning, the children get their own breakfast — toasted bagels, perhaps, or cereal or oatmeal. Later, the older girls will prepare lunch, usually a rice dish with ham and turkey chunks, peanuts, grated cheese, and canned cream-of-mushroom soup. About twice a week, they eat sandwiches with homemade bread. Meals are noisy and chaotic, with about 10 Greens squeezed around the table and the others eating at a kitchen island.

The kitchen crew cleans up after meals — children load the dishwasher (it runs three times each day), wipe off the counters, and put away the food. The third team feeds the pets, vacuums the family room, and sweeps the kitchen floor. Together, the teams do a pretty good job of keeping the mess at bay, but it’s not a perfect system. Liz reminds them during the day to tend to their duties, and crumbs and unwashed dishes often are scattered about.

Liz counts on the older girls, particularly Caroline, to help the younger children with chores and schoolwork and make sure they finish their milk at meals. After pulling out of the driveway one day to take children to piano lessons, Liz calls Caroline to report on who is where. “I have a lot of kids — I have nine,” she tells Caroline. “You have only Hannah.” Alexander, who is in the car with Liz, adds, “And Timothy.” Caroline is protective, and does not mind the responsibility.

To stock the kitchen, Liz goes to the supermarket each week, usually with four to six children who pile into their assigned seats in the 15-seat van. “We’re like a parade,” she says. Each week she buys 15 gallons of milk, 20 pounds of apples, four pounds of broccoli, and up to 20 pounds of flour, among other items, spending about $275. Once every three weeks she stocks up at BJ’s on toilet paper, soy sauce, cooking oil, rice, and other goods. That costs another $300.

The Greens are frugal. Everyone wears secondhand clothes and shoes obtained from friends, the Salvation Army, or Rescue Mission. Liz cuts the children’s hair and mows the lawn. They visit the library each week, and at any one time have up to 180 items checked out. They rarely eat out: Once a month in the winter, the family goes to Pizza Hut, where the children eat free pizzas they have earned through a reading program. With dinner for Liz and Howard and beverages for all, the evening out totals about $25. The family rarely goes out to see a movie or buy ice cream. They do spend several weeks every year at Liz’s parents’ lake house. And every Sunday, the family goes to church, and to Bible study every Wednesday.

As evangelical Christians, the Greens say their faith has played a large role in their decisions both to adopt and to home-school all the children. Home schooling, they believe, gives the children more individual attention, and it also provides more control over the children’s moral development. Because she is with her children all day, Liz says, she can better develop their character and insist on discipline and kind behavior. The family uses a home-schooling curriculum published by Sonlight, which uses a literature-based, Christian-focused approach.

Each morning after breakfast, Liz works with the children one-on-one and in groups. Since she cannot hover over each child, she encourages them to figure things out on their own. Older children spend half an hour on a subject, then move on to another. Often, the older daughters work with younger children, testing them on spelling or math facts.

The Greens realize there may be gaps in the children’s education. Liz acknowledges that it is nearly impossible to learn a foreign language by using a CD. To compensate for missing the music instruction and gym classes offered in traditional schools, everyone gets lessons in piano, tennis, skiing, and swimming. This year Caroline and Elizabeth are taking biology, Spanish, and history at a cooperative of home-schooling families. “I do feel stretched about getting everything done,” Liz says. “But if I can do the really important parts well” — in her view, math and language arts — “then they can school themselves in some of the parts I just can’t get to.” Howard explains that the goal is “to teach them to gather information on their own and synthesize it.” He says: “I want my kids to learn how to think.”

Another benefit of home-schooling, Liz says, is that the schedule allows her kids more time to be kids. The children have no “homework,” and all organized extracurricular activities end at about 3 p.m. The rest of the day, the children can play. In the winter, they sled in the backyard; in the summer, they swim in the family pool.

Most of the time, things work. The household is happy and surprising orderly; the children never seem to spiral out of control. Though they are not immune to typical sibling squabbles, they seem to care deeply for each other. Liz doesn’t get involved in every quarrel or pay attention to every request. When the younger children get too loud or rowdy, she directs them outside or to quiet down. Whining children are asked to stop their behavior or go to another part of the room. And for the most part, the children obey. If they don’t, she warns them about “consequences” — which could mean a spanking for the children 6 and under, and no sweets or privileges for the older ones.

Family members have found ways to make time for themselves. Liz savors the afternoons when the lessons are finished and the children have gone off to play. “I really enjoy it if I have time to cook in the kitchen by myself,” she says. She and Howard also have a standing Saturday-night dinner date, leaving Caroline in charge, and they get away about three times a year for weekend trips.

Caroline says she sometimes needs time and space of her own; at those times, she stays inside the house when the others are playing outside and goes to the basement to sew or work on crafts. She enjoys being part of such a large family — and she likes her own mothering role in it, even if it means she has more responsibility than most children her age. She often makes up games for the kids to play outside and leads them in songs. If Caroline had it her way, her parents would adopt more children.

She would like more privileges, she acknowledges. She wants to take acting and voice lessons, for example, but Liz explains that she can’t have them — because the Greens would have to offer private lessons to all 12 children and can’t drive all of them in separate directions. “I could only guess if I were an only child, I would get more privileges and be more spoiled,” says Caroline.

The Greens often reflect on the decisions they have made. Sometimes they wonder if they are giving their children enough individual attention. “It’s easy to adopt a crowd-control mentality, but that’s not what the children need,” says Howard. “I guess more than anything I struggle with that: Am I giving each one what he or she needs from me?” And he worries that the children one day will resent them for choosing a large family over the vacations and material goods that other children have. But he hopes they realize that “this is better than any of that.”

When they step back and look at the family they have created, Liz and

Howard feel certain that they have made the right choices. “We can’t save

all of the AIDS orphans from Africa or every abandoned baby in China ...

but we can help one,” says Howard. Relieved to be past diapers and the

toddler stage, the Greens believe their family is complete. But, adds

Howard, “If someone came to us and asked if we would take in a baby who

needed a home, we would say yes.” There’s still one seat left in the van.

![]()

Katherine Federici Greenwood is an associate editor at PAW.