|

November 8, 2006: Features

A

life at Princeton

Robert Goheen arrived on campus 70 years ago, and went on to

remake the place he loved

By Merrell Noden ’78

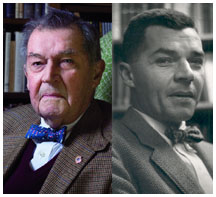

Robert F. Goheen ’40 *48, in 2006, and after being named as Princeton’s next president in 1956. (From left: Photo by Ricardo Barros; Elizabeth Menzies, princeton alumni weekly photograph collection, princeton university archives)

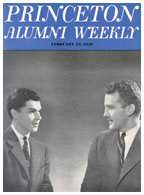

Pyne Prize winners: Goheen, left, with J.H. Worth ’40 on the cover of the Feb. 23, 1940, PAW.

Goheen shows campus development plans to students around 1960. Princeton underwent dramatic expansion during his tenure. (Princeton Alumni Weekly Photograph Collection, Princeton University Archives)

Melvin McCray ’74, who in 1996 made a documentary film about black students at Princeton, with Goheen in the Firestone Library lobby at the opening of an exhibition celebrating Goheen’s 70-year association with Princeton. (Denise Applewhite/Office of Communications) |

The spring of 1970 was an extraordinary time on the Princeton campus, as it was on college campuses around the country. The dignified restraint of civil rights marchers had given way to increasingly anarchic protests against the Vietnam War. At Columbia, Harvard, and elsewhere, student uprisings had been met by police force with dire consequences for all sides. When it was revealed that U.S. forces had invaded Cambodia, signaling a further escalation of the war, it seemed all hell might break loose at Princeton, too.

In hopes of dispelling this poisonous atmosphere, no fewer than 10 faculty meetings were held in the month of May alone. On May 4, the same day that National Guards-men shot dead four students at Kent State, 4,000 members of the University community gathered in Jadwin Gymnasium to air their views. “Everybody from the University community was invited to come and sound off,” recalls then-president Robert Goheen ’40 *48. “I think it was a healthy airing of frustration and anger.”

Few universities, if any, came through those turbulent times unscathed. It would be wrong to suggest that Princeton was the rare exception. But those who lived through those difficult days agree that Princeton had a smoother passage than most, and many insist that that was due largely to the leadership of Bob Goheen, whose example of forthright honesty during his life and the 15 momentous years of his presidency was admired even by those who disagreed with him. “There is an inner strength about Bob that is very important to him, but it was also important to the rest of us because we fed off it, and that just made so much difference,” says William Bowen *58, who in 1970 was the University provost, before succeeding Goheen as president two years later. “To have confidence that your leader was trying to do the right thing and that your leader understood himself — that was enormously reassuring to everyone.”

This fall, on the 70th anniversary of his arrival at Princeton as a freshly scrubbed 17-year-old freshman, Goheen’s contributions to Princeton are being celebrated in an exhibition in the main hall of Firestone Library. University archivist Dan Linke videotaped four hours of interviews with Goheen, excerpts from which may be viewed at the exhibition. Whether Goheen is discussing coeducation or his boyhood in India, he comes across as plainspoken and modest.

Just as Goheen has shown tremendous loyalty to Princeton and to the people who worked with him, they reciprocate with something that goes beyond respect to a deep affection. “He remains a North Star you can count on,” says Tony Maruca ’54, whose office in Nassau Hall was across the hall from Goheen’s, and who later became the Univer-sity’s administrative vice president. After Goheen had left Princeton and stood nominated by President Jimmy Carter to be the U.S. ambassador to India, Maruca was among several of Goheen’s associates who received a visit from an FBI agent performing a routine background check on the nominee. The agent slowly made his way down a long checklist of human vices and failings, each of which Maruca assured him did not apply to Goheen. Finally, the agent, unaccustomed to finding such rectitude in the world, looked up and said, in effect, “What is this guy, a saint?”

Goheen would be the first to say that he’s hardly that, just someone guided by a faith in the power of honest, clear-eyed thinking. “I place special emphasis on reflective thought,” he told incoming freshmen in 1965, and he has always believed that a university is the best place to cultivate such thought.

Today, at 87, Goheen is a bit stooped as he makes his way slowly down the hallway to the office he keeps in Robertson Hall. After a hip replacement and a replacement of that replacement, he walks with a cane. Absent this day is the bowtie that has been his natty trademark. His shirt is open at the neck, and his hair is a little mussed. Having recently returned to his home near campus from summer on Cape Cod, a retreat he has been enjoying for years, he seems relaxed and mentally sharp. Talking to him is a treat. He insists that most of the good things that have come his way have done so because of luck. “At critical points in my life things have just broken my way that I wouldn’t have expected,” he says. The Greek scholar in him attributes this to tuche, the Greek word for fortune.

Goheen was schooled early in the importance of helping other people. His parents were Presbyterian medical missionaries in the town of Vengurla, some 175 miles down the west coast of India from Bombay. “If my parents had had a middle name, it would have been ‘service,’” he says. “They were servants.” The money his father made tending to the wealthier Portuguese in the neighboring port of Goa was ploughed back into treating poor local fishermen and farmers. He built from scratch a small hospital that grew to include a leprosarium and a sanatorium for patients with tuberculosis.

There were a few other Western families, but most of Goheen’s childhood playmates were Indian. He played cricket and soccer. Young Bob spent half of the year with his family and the other half at a school run by missionaries high in the Palani Hills, at an altitude of almost 7,000 feet. Goheen says today that growing up in a racially mixed society actually may have slowed his awakening to racial injustice in the United States. “A lot of Mother’s and Dad’s very good friends were Indian families. We mixed with their children. I never thought about racial matters,” he says. “It took me a while to wake up.”

Goheen moved to the United States at 15 to attend the Lawrenceville School. He lived with his sister Alice on William Street in Princeton, and each morning he got a ride five miles down the road to Lawrenceville with Eleanor Wicks, the wife of the University chaplain, whose son, David, also was a student there. In the evenings he would hitchhike back to Princeton.

In a sign of the times, he came to Princeton with more than half of his Lawrenceville class. At Princeton, he was a star. He shared the Pyne Prize, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated summa cum laude. He joined Quadrangle Club and was quite a good soccer player. Promoted to the varsity early in his sophomore year, he played inside left, helping the Tigers to win Mid-Atlantic Championships in both his sophomore and senior years. “My main virtue was stamina,” he says. “I could run and run and run more than most people. I had no high-level skills.”

When, in 1957, Goheen succeeded Harold Dodds as Princeton’s 16th president, he was only 37, the University’s youngest leader since before the Revolutionary War. Goheen had no inkling that the trustees who had summoned him to the Princeton home of Dean Mathey ’12 (Dean by name, not by office) under the guise of wanting to pick his brain about the concerns of the younger faculty were actually interviewing him for the University’s top post. Why would he? He had heard rumors that he might be a candidate for the job, but had calculated his chances and decided that those rumors were false. At the time he was an assistant professor of classics. Despite having written a groundbreaking study of Antigone, he did not yet have tenure. He was worried enough about his family’s future to have applied for a job with the Rockefeller Brothers Foundation — which, he notes, he was never offered.

Not long after taking office, Goheen said, rather famously, that he did not want to be remembered as a “building president.” It’s a tribute to everything he achieved that that’s probably one of the last things anyone says about him now, even though the size of the Princeton campus nearly doubled during his tenure, with the addition of Jadwin Gymnasium, the University Art Museum, the Woolworth Center, the architecture building, the Woodrow Wilson School, the E-Quad, and Fine, Jadwin, and Peyton Halls for the sciences and mathematics — as well as the often-reviled New South administration building and the dormitories of the New New Quad.

Never much of a backslapper, Goheen says the part of the job he enjoyed least was fundraising. Yet one of his earliest successes was the major capital campaign the University undertook soon after he took office. He phoned deep-pocketed alumni tirelessly and had several teas with Mrs. Jadwin. He must have been pretty good at it: While aiming to raise $53 million, the campaign ultimately generated $61 million.

The Princeton we know today is still the one Goheen built with that money and with the political capital he soon commanded. “Princeton has probably had four presidents who made an enormous difference at particular pivotal moments,” says Neil Rudenstine ’56, Princeton’s dean of students from 1968 to 1972 (and later, Princeton provost and president of Harvard). “The first was [John] Witherspoon, the second was [James] McCosh, and the third was Woodrow Wilson. And I think the fourth was Bob Goheen, though he was probably the most reticent of the four and therefore made what he did the least visible.”

The major changes that took place on Goheen’s watch in the years from 1957 through 1972 include coeducation, the increased diversity of the student body, and the continued transformation of Princeton from undergraduate college to top-tier research university. While steering Princeton through truly radical times, facing criticism both from student activists and disenchanted alumni, he launched a quiet revolution whose primary aim was to upgrade Princeton’s academic program by increasing the size of the faculty, raising faculty salaries, and expanding course offerings at both the graduate and undergraduate levels.

“Bob played an enormously important role in the transition of Princeton from a very good college with pockets of excellence at the graduate level to what it is today — without argument one of the world’s great universities,” says Bowen. “He laid the groundwork for faculty recruitment and the building that has been the core.”

Goheen went out and recruited some of the top academics in the world. He lured Lawrence Stone and Robert Darnton to the history department, and, with funding from Laurance S. Rockefeller ’32, helped transform the philosophy department into one of the world’s best. In a nod to his upbringing in India, he greatly strengthened international studies and the study of languages. It was always important to him that Princeton embrace as much of the world as possible. Though a classicist himself, he championed the sciences. “It seems to me that Sputnik was a tremendous asset to American higher education because it alerted the government and a lot of other people to the importance of higher education,” Goheen says. “We got on the gravy train, too. It just made money and entrée to people much more available.”

It’s hard to imagine that anyone, Goheen included, had an inkling of how much the wider world was going to change in his 15 years as president, thanks to the civil rights movement, feminism, the Vietnam War, drugs, rock ’n’ roll, and probably some dozen other cultural forces. One key to Goheen’s success was his willingness to change with the world around him, to look at it clearly and to adjust his goals accordingly. “He was always open, always looking honestly,” says Bowen. “He never once thought, ‘How is this action or inaction going to make me look?’ He was always concerned with what is the right thing for the University.”

During the racial turmoil of the late 1950s and early 1960s, Goheen would seek out Princeton students who were active in the civil rights movement to learn more about it, and by the early 1960s he had identified diversifying Princeton’s student body as an important goal. The embarrassment he felt when student high jinks evolved into riots in the spring of 1963 was due partly to the stupidity of the whole thing but also to his shame when he compared the privileged Princeton students to their counterparts in the South. “What really made me cross was that at the same time the young people of Birmingham [were protesting] for very serious causes, here we are: Princeton held up in The New York Times as this elite group of kids having a big time destroying things.”

Bowen points out that coeducation was the unexpected beneficiary of Goheen’s strengthening of Princeton’s academic program: “When the coeducation decision came before us in the late 1960s, there was much debate about whether Princeton could afford to go coed or whether doing so would just kill [the University] financially,” says Bowen. “Well, I was the one who did the study that showed we could [afford to go coed]. Why? Because the faculty Bob had built up over the previous years was now capable of teaching a good many more students than were being taught at the time. And it was that excess capacity that made coeducation financially feasible. It was the perfect answer to all the opponents of coeducation who tended to focus on costs.”

At first, Goheen himself opposed coeducation. In 1965 he said that he believed coeducation “would bring more new problems to Princeton than it would cure”; a year later he told a PAW interviewer that “it doesn’t seem to me or the trustees that we should divert substantial resources at this point to accommodate a lot of nice young ladies, brilliant though they may be.” Whenever he discussed the pros and cons of making this momentous change, he tended to talk about how the presence of women might help the men — of their civilizing influence in the classroom. But Goheen was able to do something that is rare today in public life, saying, in 1972, “I was just plain wrong in 1965.” Today, he adds: “It’s no use pretending you’re not wrong when you are.”

In thinking about Goheen’s early views on coeducation, “it’s very important to remember how he grew up,” says Bowen. “He had been at all-male Lawrenceville and then all-male Princeton, and he had thrived. He had been outstandingly successful, so why wouldn’t he think it was a good model? But of course the world was changing, and it was to Bob’s eternal, undying credit that he understood that the University needed to operate in the world that was developing, not the world we’d lived in in the past.”

Goheen first met Bowen by chance on the tennis court at the Graduate College. That was the beginning of a long friendship and a spirited tennis rivalry. Bowen recalled that when Goheen asked him to be provost, he was hesitant to accept: “I said to him, ‘I don’t know that this is a good idea. You and I disagree on a very central matter, namely coeducation.’ I had gone to a coeducational high school and a coeducational college. Coeducation seemed to me the most natural thing in the world. I said, ‘Bob, we’ve grown up in different worlds. It’s going to be tough for us to be side by side in Nassau Hall.’

“He said, ‘Oh, no. That’s fine. I think we ought each to continue to look at this and hear the arguments and look for the evidence and see where we come out. I’m happy for you to have your own views. You should! Do your best to persuade me.’ And of course it was Bob who had the hard job — I had the easy job — which was changing his mind,” Bowen says.

Today, Goheen describes Bowen as his best friend, though they still don’t agree on everything — notably Bowen’s well-publicized concerns about the role on campus and academic performance of college athletes. “I think he exaggerates the problem,” Goheen says of his friend. “You don’t find a lot of Princeton athletes flunking out, and every now and then one wins a big academic prize.”

Coeducation was not Goheen’s only apostasy; he also had one on the Vietnam War. At first he was a quiet supporter of the war, due largely to his faith in an old service buddy. “One of my best friends, Dean Rusk, was secretary of state,” says Goheen. “And I believed in him for a long, long time, until I became convinced that he was on the wrong track. I wouldn’t say it was the protesters that changed my mind. It was the war itself.”

Though he was critical of student protesters, he did not object to their opposition to the war. By that time he, too, was against it. Goheen was one of 37 university presidents who in 1970 signed a letter urging President Richard M. Nixon to bring the troops home. And at home, his wife, Margaret, was so vehemently against the war that she earned herself a place on Nixon’s famous “enemies list.”

No, Goheen’s objection to the protesters was that they had no use for the civilized debate he so valued. “The SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] membership included a lot of people who were just deeply radical in their thinking and really totalitarian in wanting to impose their views on everybody else,” says Goheen, sounding a bit miffed even to this day. He was always a great believer in the virtues of talking and listening. As much as he has learned from the ancient Greeks’ passion for debate in the public square, there is also a good bit of John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty in Goheen, in his faith that civilized debate can nudge us closer to the truth. “Somebody once told me that you should never trust anyone who thinks he’s right more than 85 percent of the time, and I think that’s right,” Goheen muses.

Of course, not everyone was pleased with the pace at which Princeton was changing, and Goheen was attacked from both sides. On the left, activists felt he was not forceful enough, and that he settled for small changes when problems called for seismic shifts. Writer, translator, and Princeton emeritus professor Edmund Keeley ’48 recalls how Goheen, who had been president of Quadrangle Club, defended the eating clubs at a time when others, including a number of alumni on the faculty, were pushing to make them more inclusive. “Those of us who had been through the club system and had begun a revolt against the horrors of bicker, and the people who were left out, were quite disappointed,” says Keeley, who otherwise supported Goheen over the years. “I saw no possibility of change if the administration supported the clubs.” A decade later, the Prince, in a dispute with Goheen over University governance, wrote an editorial calling him unfit for office. (Three years after that, a different editorial board praised him as “a superlative example” of a president.) On the right were conservative alumni who were angry at the direction in which he was taking “their” Princeton, not just through coeducation, but — in their view — by being too lenient with rule-breakers, lowering standards of sexual morality, and failing to support ROTC. Margaret Goheen believes that the heart attack her husband suffered in 1981 was brought on by the accumulated stress of his last few years as president.

These days Goheen spends much of his time reading. He raves about a book recommended to him by one of his children called The Long Walk, written by a Pole who escaped from a Siberian prison camp and walked all the way to India. He adds, a bit sheepishly, that he also enjoys P.D. James. There is also more serious reading, mostly foreign policy journals and books, many of them about the current administration in Washington, whose actions he plainly deplores. “This administration is so bad it’s shocking,” he says.

Years ago, he was shocked to hear the late sociology professor Marion J. Levy Jr. call him a conservative. Certainly, there is no mistaking Goheen for one of today’s neocons. “He’s a conservative like Edmund Burke,” offers Rudenstine, who as Princeton’s dean of students served on the front line of many student protests. Like the author of Reflections on the Revolution in France, Goheen has a respect for institutions and values that have stood the test of time. He is wary of sudden, radical shifts. “I guess I am conservative in terms of the values of the liberal tradition,” he allows. “That’s what I want to conserve and perpetuate.”

Goheen once described himself as an “Augustinian optimist,” explaining that he meant that while we live in an imperfect world and keep getting things wrong, progress is possible in small incremental steps. Lately, though, he seems to have lost some of that optimism.

“I get a bit gloomy at times because of the state of the world,” he says. “This clash, or divide, between so much of the Muslim world and ourselves is going to go on and deepen unless there’s enormous change in this country. Our foreign policy has been wrong, or 65 percent wrong, for the last two decades. We ought to develop a new foreign policy that is not only sympathetic to our European friends, but really is reaching out to better understand and deal with the non-European world as well. It’s not a matter of just investing money. [It’s also] our attitudes and how we listen and how we try to work [with other countries].”

Nuclear proliferation has been a special concern for years. His years as ambassador to India coincided with a chill in that country’s relationship with the United States, due largely to nuclear issues. When he returned to Princeton in 1981, he oversaw a Woodrow Wilson School policy task force on the subject. In a 1982 interview with journalist and playwright William McCleery, who edited Goheen’s papers into the book The Human Nature of a University, it sounds almost as if he were looking ahead 24 years: “Until the superpowers show some restraint, they are in a weak position to discourage horizontal proliferation.” Today, on the subject of Iran and its nuclear aspirations, he says matter-of-factly, “They’re going to have it [the bomb]. We could have come to this point in a much more graceful way, with much more international cooperation. We’re a lone soldier now.”

Mostly, though, as he looks back on a long life of service — to Princeton, to his country, and yes, to the values of the liberal tradition he so esteems — Goheen has few regrets.

“I did my best,” he says simply. “That’s all

I can say.” ![]()

Merrell Noden ’78 is a frequent PAW contributor.