|

November 8, 2006: Notebook

A ‘welcoming place’ for the LGBT community

FYI –Findings

Towering intellect

Stories with a ‘grunt’s-eye view’ of Afghanistan

Kamras ’95: Weed out bad teachers, pay best more

Massey ’77 honored for research, mentoring

PEAR lab’s ‘strange garden’ prepares to close

PPPL contract to go out to bid

Debra Bazarsky, left, director of the LGBT Center, with Caitlin Edwards ’07 and Larry Lyons GS at the opening of the center’s new offices in Frist Campus Center. (Frank Wojciechowski)

Ellen Adams ’10 speaks about the importance of visibility for all members of the LGBT community at a National Coming Out Day rally Oct. 11 at Frist. (Hyunseok Shim ’08) |

A ‘welcoming place’ for the LGBT community

When Kristopher Kersey ’04 and other members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Task Force presented their ideas for an LGBT student center to President Tilghman in the fall of 2003, they expected their proposal to be challenged. “We had so many reasons to defend it, and we had practiced defending it,” Kersey recalled. “And she just said ‘yes’ at the end. We walked out of Nassau Hall and just stood there and looked at each other. We didn’t know what to do.”

On Oct. 12, when the LGBT Center officially opened its doors in the Frist Campus Center, Kersey and others in the University’s LGBT community knew exactly what to do: celebrate.

The center’s arrival highlighted a weeklong series of LGBT events that in- cluded the annual Gay Jeans Day Oct. 11, during which the Pride Alliance handed out 850 “Gay? Fine by me” T-shirts, and a dance party at the New South administration building the night of the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

With offices, a library, a lounge area, and a cluster of computers donated by the Fund For Reunion, the University’s LGBT alumni group, the new center will serve as a home for LGBT student organizations and programs as well as a hangout and study space that will be open until midnight.

Tilghman, who spoke at the dedication, said that she was excited to be opening the center but even more excited to see the more than 100 people who flooded the center’s entrance and the hallway outside it. She credited Debra Bazarsky, the center’s director, for improving LGBT services at the University in the last five years. Earlier this fall, Princeton was named one of the country’s top 20 campuses for LGBT students by The Advocate Guide for LGBT Students. “I was much prouder of that than I was of our U.S. News & World Report ranking,” Tilghman said, explaining that Princeton’s top ranking in the latter publication was nothing new.

The Advocate Guide rated the “gay point average” for universities and gave Princeton 19 out of a possible 20 points, highlighting campus events, administrative support, and the Fund For Reunion as major factors. Bazarsky was happy to be recognized but said the campus can do more, particularly in supporting its transgender students.

Graduate student Larry Lyons, who spoke at the center’s opening, agreed that Princeton has room for improvement. “The truth is that Princeton could be doing much, much more to eradicate a generations-old legacy of racism, sexism, homophobia, and, of course, classism,” said Lyons, a gay, black, first-generation college student pursuing his Ph.D. in English. “I feel like students like me are precisely the reason that Princeton needs so desperately for the LGBT Center to exist — not only to exist but to thrive and to flourish.”

For others, the opening was a symbol of how far the University’s LGBT community has come in recent years. Gabriel Barrett ’02, who drafted the first LGBT Center proposal as an undergraduate, flew in from London to see the new space. Barrett said that when he was a freshman at Princeton, an LGBT Center seemed “almost impossible.” But Bazarsky’s arrival changed the atmosphere for gay students, and by 2002, a center was the next step, he said. “I felt like it was something that would be timeless,” Barrett said. “We wouldn’t be relying on one amazing person to bring the queer community together on campus.”

Caitlin Edwards ’07, an LGBT peer educator, said that the center

is more of a personal resource than a symbol. “The center has now

provided somewhere where I can be my own person, where I know that despite

anything that goes on, there’s someone else that I can relate to,”

she said. “It’s just such a welcoming place. I’m so

glad we have it.” ![]()

By B.T.

|

(Illustration by Steven Veach) |

FYI

–Findings

Towering

intellect

Taller adults earn higher wages than their peers, on average, and researchers

have tried to explain the connection with hypotheses about factors such

as self-esteem and discrimination. Princeton professors Anne Case *88

and Christina Paxson have put forth a simpler reason: “On average,

taller people earn more because they are smarter.” According to

their recent working paper, taller children generally have significantly

better cognitive skills, a correlation that Case and Paxson trace to health

and nutrition, not genetics. The authors say that the difference in cognitive

skills begins as early as age 3, before children start school. The data,

which was gathered from subjects periodically from childhood through their

30s and 40s, showed that tall children are likely to become tall adults,

and tall adults continue to show better cognitive abilities, as well as

a propensity for choosing higher-paying jobs that require advanced math

and verbal skills. ![]()

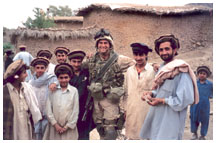

Graduate student Ross Cohen, in military gear with villagers in eastern Afghanistan, drew on his Army experiences for two recently published short stories. (Courtesy Ross Cohen GS) |

Stories with a ‘grunt’s-eye view’ of Afghanistan

In a short story by Army veteran and Woodrow Wilson School graduate student Ross Cohen, the narrator compares Afghanistan to a 50-pound machine gun: “[I]t sucked, it was awkward, and it was a pain in the ass to clean.” The story provides, in Cohen’s words, a “grunt’s-eye view” of deployment in the mountainous Khost-Gardez region.

That view was released to a national audience in September through Operation Homecoming, a book sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts and published by Random House. More than 80 soldiers, sailors, Marines, airmen, and family members connected to the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan published stories, journals, and personal correspondence. Andrew Carroll, the project’s editor, is scheduled to speak at Princeton Dec. 6.

Cohen, a Brown graduate who enlisted in the Army after 9/11, kept a journal during his 10 months in Afghanistan, but he chose to write fiction to capture his experiences, contributing two semi-autobiographical short stories that employ the crass but colorful language of military life. The stories are “pretty close to reality,” according to Cohen. “The important thing is the impression that the story is trying to give,” he said, “and I didn’t want to let a particular fact get in the way of giving the overall impression.”

While Cohen said he enjoys writing, his career plans are more in line with those of his Wilson School classmates. He worked as an intern for New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson last summer and hopes to return to Richardson’s office after receiving his master’s degree next spring.

Cohen was honorably discharged in 2005, and his experience in the military

still shapes his view of conflicts abroad. Said Cohen: “It makes

me realize [that], without American involvement, how bad some situations

are, and [also] the limits of American involvement, in a much more nuanced

way than if I hadn’t served.” ![]()

By B.T.

Jason Kamras ’95 is back in his Washington, D.C., classroom after a year’s dialogue on improving schools. (Maya Gilliam, district of columbia public schools; courtesy national teacher of the year program) |

Kamras ’95: Weed out bad teachers, pay best more

After being selected as the 2005 National Teacher of the Year, Jason Kamras ’95 spent the past year meeting with educators and parents across the country. “A lot of places were looking for some inspiration,” said Kamras, who focused on raising the bar for students in low-income communities. A math teacher at John Philip Sousa Middle School in Washington, D.C., he spoke with PAW associate editor Katherine Federici Greenwood.

What do we need to do to close the achievement gap between children in low-income communities and children in wealthier areas?

It all comes down to people — getting quality teachers and school leaders to serve in our public schools, and in particular in communities that have struggled. ... I don’t define quality in traditional terms — how many years of experience you have, or if you have a master’s, or if you’ve taken all the right education courses. Rather [I define quality] in terms of your belief in the ability of all children to learn and achieve at high levels, and your ability to bring that to fruition.

How do we get more high-quality teachers and school leaders to serve in public schools?

We need to face a difficult truth — that not all educators are effectively serving their children. I’ve taken this year to challenge my professional unions to be a lot more progressive about embracing policies that make it easier to transition out people who are consistently ineffective.

The second thing is to create school environments that are attractive to ambitious, high-performing people. We need to get rid of the “It’s always been done that way so that’s why we’re doing it” attitude in education. Ambitious teachers and school leaders want to try new things, they want to push the envelope, they want to extend the school day or extend the calendar or teach a completely integrated curriculum.

The third thing we could do, particularly at the federal level, is create some financial incentives to bring these great people to serve in low-income schools. ... I imagine a federal program that would offer bonuses of $20,000 every year to any teacher serving in a low-income school whose students, let’s say, perform in the top quartile of the school system’s standardized test performance. I would go even so far as to offer an extra $20,000 every year for math, science, and special-education teachers whose students also met this requirement. That’s because we have great difficulty attracting people in those fields. So a math teacher who works in a low-income school and whose students meet the performance targets would get a $40,000 bonus.

How did the teachers’ unions react to your ideas?

The union response has been mixed. Some officials I’ve spoken

to have been receptive, while others have been much less so. I am sensing

there’s a growing rift within the union community between those

who continue to adhere to more traditional policies, and those who are

willing to entertain more progressive ideas. I think the important thing

here is to keep a dialogue open, to keep talking, and to always think

first about what’s best for children. ![]()

MORE ON THE WEB: Click here for an extended interview with Jason Kamras ’95

(Photo by Hyunseok Shim ’08) |

“Perhaps what we are hearing now is no more than a tiny voice calling out from the bottom of a well. It suggests that we are seeing the start of disillusionment, round three. This is not just evangelicals disillusioned with parties, but with politics.”

Laurie Goodstein, national religion correspondent for The New York

Times, who said that evangelical Christians previously had become

disillusioned with Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton. She spoke Oct. 16 in

Robertson Hall on “Backlash: Are Evangelicals Disillusioned with

Politics?” ![]()

Professor William Massey ’77, foreground, with three of his protégés, from left, graduate student Robert Hampshire and Duke University professors Arlie Petters *91 and Otis Jennings ’94. (Steve Exum, courtesy SEAS) |

Massey ’77 honored for research, mentoring

November is shaping up to be a special month for William Massey ’77, the Edwin S. Wilsey Professor of Operations Research and Financial Engineering. On Nov. 4, he was slated to receive the Blackwell-Tapia Prize from the Institute for Mathematics and Its Applications, in recognition of his research and his work as a mentor for young scientists from underrepresented minority groups. Two days later, he was to be inducted as a fellow of INFORMS, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences, along with ORFE colleague Robert Vanderbei.

For Massey, who joined the Princeton faculty in 2001, the awards recognize a body of work that began in the University’s math and physics classrooms, spanned two decades in industry as a researcher at Bell Laboratories, and continued to grow when he returned to academia. The turning point came at the end of his senior year at Princeton, when Massey earned a fellowship for graduate study from a Bell Labs program for minority students created by black scientists like James West, inventor of the modern microphone, to assist the next generation of black scientists.

The program, Massey said, inspired him to help those who followed him. In addition to mentoring graduate students during his time at Bell Labs, Massey created an annual conference for black mathematicians, the Conference for African-American Researchers in the Mathematical Sciences (CAARMS), in 1995 and raised funds to fly in graduate students to participate. “You’re a creature of what you’re exposed to,” he said. “To me, it just seems natural. It was just what you were supposed to do.”

At the same time, Massey developed a reputation as an innovative researcher in queueing theory, an area of mathematics that examines waiting times in systems such as telecommunications networks by combining probability and optimization. Ehran Çinlar, the Norman Sollenberger Professor in Engineering, was so impressed with Massey’s work that he tried to lure him into academia for nearly 20 years, starting in 1981 when Çinlar was at Northwestern. “He always understood that he could come wherever I was, anytime he wanted,” Çinlar said. “He had a blank check from me.”

Massey maintained connections with Princeton, serving as the president of the Association of Black Princeton Alumni, teaching for a semester in 1990, mentoring Arlie Petters *91, an MIT Ph.D. who completed parts of his graduate studies at Princeton and later taught in the math department, and advising the senior thesis of Otis Jennings ’94. (Petters and Jennings are now professors at Duke.) Massey also maintained the mind-set of an academic. Robert Hampshire, an ORFE graduate student, was a summer intern at Bell Labs when he first saw Massey giving mathematics lectures after work, complete with photocopied notes for the audience. “It was clear that he should be a professor,” Hampshire said.

While Massey is enjoying his time on the faculty, he said that the University

could learn some lessons from the Bell Labs model of the ’70s, ’80s,

and ’90s, in which researchers from all disciplines worked under

one roof and collaborated on interdisciplinary projects. Industry labs

also set an example for recruiting talented minority scientists. “Bell

Labs saw their first black scientist in 1942,” Massey said, “whereas

Princeton didn’t see its first black engineering professor until

1999.” ![]()

By B.T.

Dudley Saville, the Stephen C. MacAleer ’63 Professor of Engineering

and Applied Science, died Oct. 4 at his home in Princeton at the age of

73. A member of the faculty since 1968, Saville was a pioneer in the fields

of fluid mechanics and colloid science. His research formed the basis

for applications in areas ranging from ink-jet printing to the production

of high-performance fibers. In the 1980s and 1990s he led a series of

experiments conducted by astronauts aboard the U.S. space shuttles. ![]()

Robert Jahn ’51 *55, next to the PEAR lab’s random mechanical cascade device, has spent 27 years researching engineering anomalies. (Hyunseok Shim ’08) |

PEAR lab’s ‘strange garden’ prepares to close

Sometime next spring, the Prince-ton Engineering Anomalies Research laboratory (PEAR), a little-known but sometimes-controversial participant in the University’s research community, will clear its shelves and close its door, bringing an end to 27 years of exploring mind-matter interactions in a scientific context.

Located on the ground floor of the E-Quad’s C-wing, the lab seems out of place, with a well-worn couch, wood-paneled walls, and a collection of aging game-like devices on which many of the lab’s trials were performed. When Robert Jahn ’51 *55, professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering emeritus, first proposed the lab in the late 1970s, its mission also seemed out of place, or at least out of the mainstream.

Jahn, the dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences from 1971 to 1986 and an expert in rocket propulsion, was intrigued by a student project related to psychic phenomena. He recognized that many engineering disciplines — electrical, chemical, and bioengineering — had roots in other sciences. “The one interface that hadn’t really been explored was that of psychology — the human mind,” Jahn said in a recent PAW interview. “What could engineering utilize, in terms of basic knowledge of how the mind works?”

With support from benefactors such as James McDonnell ’21 and Laurance Rockefeller ’32, Jahn launched PEAR to test for and characterize unexplained phenomena generated by the interaction of humans and machines. There was no curricular element — Jahn said that was “too hard for the University to digest” — but the lab developed a working relationship with an engineering course called “Human-Machine Interactions.”

Professor Alain Kornhauser *71, who has taught the course with Jahn and faculty from the psychology and philosophy departments, said that students were generally skeptical but stimulated when they visited the PEAR lab. “[The PEAR researchers] tried to take a really objective, scientific, data-based approach to the problem,” Kornhauser said. “I thought it was laudable, whether or not one believes in the outcome.”

The lab employed as many as seven full-time researchers and amassed mountains of data, including millions of trials from its random-event generator, a device that produces a series of 0’s and 1’s while users try to influence its output by favoring one or the other. PEAR also has published about 200 papers; most appeared in the Journal of Scientific Exploration, which covers a range of topics on the fringes of conventional science, from UFOs to the search for Sasquatch. (Jahn serves on the journal’s editorial board.)

Jahn’s general conclusions are that anomalous phenomena are real, can be studied scientifically in large data sets, and could be used in applications. He admitted that some of his faculty colleagues view the research with skepticism, and others have been completely dismissive. But he does not think

that the engineering anomalies work affected his reputation as a distinguished researcher in electric and plasma propulsion. Princeton’s Electric Propulsion and Plasma Dynamics Laboratory, which Jahn started in 1961, remains at the vanguard of the field under the direction of one of Jahn’s former students, Edgar Choueiri *91, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering.

PEAR will not enjoy the same fate. International Consciousness Research

Laboratories, a not-for-profit group associated with PEAR, supported research

in recent years, but with no viable long-term successor and most of the

lab’s funding evaporating, Jahn has decided to close the lab, with

no regrets. “Without a doubt it has been the most personally stimulating

and rewarding intellectual activity I’ve ever been involved in,”

he said. “I feel very privileged for having been allowed to take

a scholarly walk into this extraordinarily strange garden.” ![]()

By B.T.

|

Julie Young, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, lectured on the science behind martial arts and participated in a demonstration of several martial arts disciplines Oct. 18 outside the Friend Center. She was joined by master Hsi Lee. In her talk, Young explored the importance of posture, making analogies to engineering and architecture, and explained mathematically how a human hand – moving at a speed of 10 feet per second – can generate enough force to break a concrete block.

![]()

PPPL contract to go out to bid

“Outstanding” was the latest federal rating of Princeton’s management of the Plasma Physics Lab. (courtesy PPPL) |

Federal officials have decided to put the management of the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab up for competitive bidding for the first time, and the University has vowed to “compete aggressively” to retain the contract.

Princeton has operated the lab, a leading magnetic fusion energy research center, since it began in 1951 under Professor Lyman Spitzer *38, a founder of the field of plasma physics.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science supports 10 national science labs, and has begun requiring competitive bidding for their management and operations. After learning that the contract for the Plasma Physics Lab would be put out to bid next spring, President Tilghman said that Princeton is “committed to making the strongest possible case for continuing to manage PPPL, as we have done successfully for many years.”

The lab has received an estimated $372 million in federal funds in the past five years, including $77 million for the year that ended Sept. 30 — about 7.4 percent of the University’s total annual budget. PPPL has 415 employees, with two serving as Princeton faculty members. The facility is located on 88 acres on the Forrestal campus that are leased by the federal government.

Princeton offers a graduate program in plasma physics within the Department

of Astrophysical Sciences; 231 doctoral degrees have been awarded since

1959. ![]()

By W.R.O.