|

March 7, 2007: Features

Dream jobs

By Mark F. Bernstein ’83 and Brett Tomlinson

The rat race. The grind.

Fairly or not, the workaday world gets a bad rap. People love to complain about their jobs, and TV shows such as The Office make the daily work routine seem dreary indeed. Some lucky Princetonians have found their way to employment nirvana, however — and it is perhaps no coincidence that many work for themselves. It may not make your own Monday morning any cheerier, but consider these alumni who have what PAW considers some of the coolest jobs around.

Jason Williams ’98 at the AT&T research facility in Florham Park, N.J., where he finds spaces that spark imagination. (Ricardo Barros) |

Jason Williams ’98

“Inventive researcher”

As a child, Jason Williams ’98 loved to invent, creating new devices that were either useful, entertaining, or both. When he was 8 years old, he created a burglar alarm for his room to alert him when his brother was approaching. He later moved on to build tree forts with platforms accessible by ropes, pulleys, and zip lines; exploding birthday cakes; and a shoulder-mounted rocket launcher built with PVC piping. In high school, he converted his old Commodore 128 computer and joystick into a control module for a dance-floor light machine for his budding disc jockey business.

Today, the devices are different, but curiosity and tinkering remain integral to his daily life. Williams works for AT&T research in Florham Park, N.J., where he builds programs that enable computers to converse with people using spoken language. A spoken-dialogue computer system has three basic components: an ear, a mouth, and a brain. Williams’ work focuses on the brain, and he uses a combination of engineering, mathematics, and computer science to improve the ways in which computers interact with users.

What does an “inventive researcher” do on a typical day?

My average day is kind of divided into thirds. There’s a third learning. I’m reading about a new bit of math, going to a talk, understanding something that someone else has done that’s related to what I do, and talking to people in the rest of the company about what kinds of real-world problems they have. And then I spend about a third of the time thinking, pretty much staring off into space — thinking about how to put the pieces together. ... Some of my most productive days have been when I’ve filled up about one page in my lab notebook, and then that gave rise to about a month or two of productive stuff. And then the other third is implementing and communicating: writing computer programs that test the theories, and writing papers. We all publish in journals and at conferences.

Do you have a specific creative process?

First, I really try to do my homework. I try to understand what other people have done. There’s really not a lot of excitement in reinventing something. [Also] I try to be pretty diligent about formulating things in a mathematical way. ... But beyond that, I don’t know. Maybe if I could articulate it better, I’d spend less than a third of my time staring off into space.

Do you work best in an office, or are you more creative elsewhere?

Some of my best ideas have come to me either while in the shower or while doing the dishes, so I sometimes wonder if I should install a little bathroom and a little sink in my office and have everybody bring in their dirty dishes.

Michael Kass ’82, left, and stills, above, from the animated movie “The Incredibles,” which used the software he developed around 1995 to make characters’ clothing “move” with the characters. (Photo: Tami Reed, Danger Buttons Productions; “The Incredibles” images: © 2004 Disney Enterprises, Inc./Pixar Animation Studios)

|

Michael Kass ’82

Senior scientist, Disney/Pixar

Michael Kass ’82 planned to be a physics major when he arrived at Princeton, until he discovered “that all the easy problems had been solved.” Instead, he designed his own major in the field of artificial intelligence. That led to a master’s degree from MIT and a Ph.D. from Stanford. Landing in the middle of the burgeoning Silicon Valley, Kass joined Apple, where he worked for five years in its research division. His work brought him to the attention of Pixar, which he joined in 1995, just as the movie Toy Story was being made.

Kass designed a software program that replicates the movement of clothing, hair, and fur on animated characters, a program that has been used in all of Pixar’s films since his arrival. In his spare time, Kass is a competitive figure skater and a past U.S. juggling champion.

Is it true that you’ve won two Oscars?

A short film I worked on, called Geri’s Game, won an Oscar in 1997 as best short animated film. It was the first animated film in which the characters’ clothing actually moved with the character, rather than looking as if it had been painted on. I got to go to the ceremony, but only the director actually received a statue and got to go on stage. In 2006, two colleagues and I received an Academy Award for scientific and technical achievement. But it’s a plaque, not a statue, and it is not officially called an Oscar.

Because you deal with clothing, do you have to know about fashion?

When we worked on Geri’s Game, when we were first developing the technology, Geri’s jacket looked like a T-shirt. So we tried putting lapels on it, but then it looked like a T-shirt with lapels. Eventually we figured out that the problem was that we had added the jacket to his character with the arms straight out from the sides. There were no wrinkles, and the only garment that moves that way is a T-shirt. We had to put his arms at his sides when we added the jacket and then enter a different set of calculations for that kind of garment. That’s what you get when you put a bunch of Ph.Ds who had never sewed a stitch in their lives on a project like this. Now we also consult with a tailor.

How will animation change in, say, the next 10 years?

It used to be that there were a lot of things — such as clothing — that couldn’t be done very well at all in animation. Now, if you’re willing to spend the money, you can do almost anything. What will change is that the price for doing those things will come down.

Has the use of computer animation software undermined the skills of the old animators, who used to do everything by hand?

In general, the older animators appreciate what Pixar has done. If you can develop tools that will make it easier to create, what you’ll see is a lot more quality animation.

Celebrity writer Alisa Lipsky-Karasz ’00 at the Metropolitan Opera’s annual opening night gala in New York in September. |

Elisa Lipsky-Karasz ’00

Associate editor, Women’s Wear Daily, W magazine

Oh, for the life of red-carpet awards shows, gallery openings, and parties. Such is the work world of Elisa Lipsky-Karasz ’00, who covers the rich and famous for Women’s Wear Daily and W magazine. Though not a gossip columnist, as she is quick to point out, Lipsky-Karasz also has done the celebrity beat for the New York Daily News and the New York Post. Her journalistic career seems to model that of Andy Sachs, the erstwhile young career woman in The Devil Wears Prada: personal assistant to the editor of Harper’s Bazaar (then Katherine Betts ’86) right out of college, then newspaper stints covering celebrity news for the New York papers before taking on her current assignment.

What exactly do you do?

We — the people I work with and I — cover all the major New York parties and events, the big movie premieres. We have the ability to interview people we admire. I recently got to go to the National Board of Review gala and found myself sitting at a table with [actors] Forest Whitaker and Mark Wahlberg. I get to cover Fashion Week in Paris. There is nothing more glamorous than a fashion show. I’ll never get tired of that.

Does any of it ever get old?

Sometimes I’ll say, “Oh my God, if I have to drink one more glass of champagne,” but then I’ll catch myself and think, “Who am I kidding?” You just have to make sure you get your sleep.

Why are we so fascinated by celebrities?

Basically, it’s reality television acted out in the tabloids. In our society, people are influenced by what clothes celebrities choose to wear. It has a big influence on the fashion business. If celebrities attend a particular benefit, that has a ripple effect in encouraging other people to be more excited about that cause.

Has celebrity reporting gotten too intrusive?

There’s a slippery slope. There are some people who beg for all the attention they can get, but then it gets out of hand. Some celebrities clearly foster relationships with the paparazzi. They promote it, and I don’t have a lot of sympathy for them.

NFL side judge Laird Hayes ’71 at Super Bowl XXXVIII in 2004. (Kent Smith, courtesy Carolina Panthers) |

Laird Hayes ’71

NFL official

Even with more than a decade’s experience, Laird Hayes ’71 still gets “those butterflies every week.” His job can be nerve-wracking: Each workday is televised, and afterward, his bosses evaluate every move he makes in a detailed report card.

Hayes is a side judge in the NFL — one of the seven officials responsible for enforcing rules on the field. Since joining the league in 1995, he has been chosen for the Super Bowl officiating crew twice, in 2002 and 2004, and he has worked at least one playoff game in every year but his first. Long before his NFL days, Hayes got his start refereeing intramural basketball games as an undergraduate. When he began graduate school in California, he continued working as a basketball referee and added baseball and football as well. Hayes also teaches physical education at Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa, Calif., and he says that his success in officiating has relied on an understanding family, which has adjusted to his being away from home for about 25 weekends each year.

Your job involves keeping up with the fastest players on the field. What do you do to stay in shape?

First of all, I get a 23-yard head start — I’m 23 yards downfield at the snap, and I’m running backward. Sometimes you do get beat if it’s a long pass because some of these guys are world-class sprinters. But my exercise routine is lifting weights every day — upper body and lower body. I walk, I run, I play golf, I swim — infrequently — and I surf. Those things help with cardiovascular [fitness].

Working so close to the sideline, you must hear a lot from the coaches. Is it ever helpful?

I think that most of it, you block out. It’s the whole Chicken Little deal: If you hear the same stuff over and over and the guy just never stops, then you’re going to start tuning it out. If a guy like [former Cowboys coach] Bill Parcells says something, you’re going to listen to it, because he doesn’t say anything. ... If he says, “I think you guys missed that one,” when I look at my videotape, I’ll go to that play.

Fans in the stands also have plenty to say about referees. Can you hear them yelling?

Uh-huh [laughs] — I should probably say no, but yes, I can hear them. Some of it’s kind of amusing, but they get nasty. They’re fans. The derivation is from “fanatic,” and some of them are.

What was it like being at the Super Bowl for the first time in 2002?

I wish I could say it’s just another game. Right until the ball was kicked off, that was just another game, and then all of a sudden, I don’t know what on earth happened, but it just wasn’t another game. It was pretty intense. The players aren’t any more intense, the coaches aren’t any more intense, but you just kind of realize the enormity of the whole deal and how lucky you are to be there. You just hope you don’t screw it up.

Ken Block ’57 founded Matterhorn Travel in Annapolis, Md. (Lisa Helfert) |

Ken Block ’57

Travel entrepreneur

Even as a young Foreign Service officer in the 1960s, Ken Block ’57 was an explorer. When his work was done, he did his best to leave the office far behind: skiing in Switzerland, meandering through the countryside in Bangladesh. When Block decided to leave the Foreign Service and start his own business, travel seemed a natural fit.

After more than four decades in the business, Block laughs about how little he actually knew about the travel industry back then. He built Matterhorn Travel, his Annapolis, Md.-based company, by chartering flights to Europe, but his focus soon shifted to educational tours. Matterhorn now operates European tours that cover two basic historical categories: World War II and classical music. Block scouts every detail before he adds a new piece to a tour. Last year, he traveled to Poland twice to plan a new leg of the classical music series that explores the life and work of Frédéric Chopin. He also visited the Hürtgen Forest just east of the German-Belgian border, the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the war in Europe and a new addition to the World War II tours.

What are the two or three must-see sites for World War II buffs visiting Europe?

I would say the Normandy beaches — Omaha and Utah beaches, where the Americans landed on June 6. There were three other landing places by British troops, but my whole activity has been directed toward the American campaigns. [Also] Bastogne, which was one of the two fierce pressure points of the Battle of the Bulge, and Buchenwald, the former concentration camp. Anyone who wants to get an understanding of what the war was about and the Nazi ideology has to understand what came to be called “the Final Solution.”

Which composers are the most beloved by your tour-goers?

Bach and Mozart, by far. I think Beethoven is played more by symphony orchestras, but for our people, it’s Bach and Mozart.

Your work takes you to at least a half-dozen countries each year. What do you do for vacation?

A lot of people ask me that, and I always reply, “My favorite place is Annapolis, Md.” I grew up here. I never assumed that I would go anywhere else to start my company. I love it here. ... My idea of doing something pleasurable is to be in Annapolis, to read, to walk. Of course, you’re talking to someone who is 71 now, so I would have perhaps given you a different answer 10, 20, 30 years ago.

Penelope Finnie ’82 pushes her products at her café, Bittersweet. (courtesy Bittersweet Café) |

Penelope Finnie ’82

Chocolatier

Having hit it big in the dot-com explosion during the 1990s as one of the founders of the search engine Ask Jeeves, Penny Finnie ’82 turned her sights to ... chocolate. In London several years ago, Finnie visited a chocolate maker and realized that chocolate can be as varied and complex as wine, and its taste as rooted to the place where it comes from. She and her business partners decided to open Bittersweet, a café dedicated to selling different types of chocolate from around the world and to educating people about their variety. They now have two cafés, in San Francisco and Oakland, which also offer an array of chocolate-based drinks and host chocolate tastings. Finnie and her partners recently have begun to make their own chocolate.

Is there such a thing as a chocolate snob?

Oh, yes. Even my children are chocolate snobs now! There are a lot of 20-somethings in the Bay Area. They really want to know the differences between types of chocolate. They’ll come in and ask, “Can you recommend something with a darker profile?”

How can you be around chocolate all day and not gain weight?

The bars with the highest percentage of cacao in them don’t contain much sugar, and you just can’t eat very much at a time. You take a bite, and that’s it for the day.

Does chocolate really have medicinal properties?

Our No. 1 seller is a bar that’s 90 percent cacao, and it is very high in antioxidants, which lower your cholesterol levels. Our San Francisco store is right across the street from a hospital, and one of their cardiologists sends his patients in.

You have said that chocolate is like wine. Can you recommend a chocolate that goes well with, say, veal?

A lot of chocolate is starting to go with food. A restaurant came to us and wanted a chocolate to go with foie gras. We recommended a Scharffen Berger — it’s very full-bodied, with an oak finish.

Maria Armstrong ’84 in her “office” atop Big Mountain in Whitefish, Mont. (Kathy Sullivan/Mountain Photography) |

Maria Armstrong ’84

Ski instructor

Can’t decide whether to ski this winter at one of the popular resorts, such as Aspen, or strike out for the relatively undiscovered slopes of Whitefish, Mont.? If you are Maria Armstrong ’84, you can do both. Armstrong, who has been a ski instructor at Big Mountain in Whitefish for the last 20 years, decided this season to split her time and recently returned to Montana after several weeks of teaching in Aspen.

At Princeton, Armstrong skied competitively for Princeton’s club team; after graduation, the Kalispell, Mont., native knew that she wanted to be back home in the mountains. Planning to ski for a few years before “falling into the corporate world,” she now finds herself giving both private and group ski lessons, where “work” demands more runs down the pristine powder. During the warm-weather months, Armstrong helps her husband, an architect, as his office manager.

What is the difference between Eastern and Western skiing?

In some ways, they’re more similar than they are different. In the East, you have different topography and more deciduous trees, which are denser and you have to ski around them. In the West, you find more pine, fir, and larch, and you can ski right among them. There’s also more humidity in the East, so the snow is denser and harder. When people out here say our conditions are icy, I say, go back East and you’ll see what icy ski conditions really are.

Can anyone learn to ski?

In my belief, yes. I’ve taught 21/2-year-olds, and I’ve taught a woman in her 70s. We’re seeing more and more retirees who are taking up skiing.

When did your daughters first ski?

When they were in the womb — I skied when I was pregnant. They first got on skis when they were about 21/2. By the time you had put on their skis and goggles and mittens, it would be time to go in for hot chocolate. And that was fine.

Whitefish is less well known than some other ski destinations. Is it growing?

People who know both places say that Whitefish is what Aspen was 30 years ago. Whitefish is in the Rockies, but it’s at a lower elevation — our summit is about 7,000 feet, compared to 12,000 in Aspen. So Aspen tends to be sunnier and drier. But we’re growing. People are coming in and building houses.

Bruce Hall ’46 testing his product in the tasting room of his Oregon winery. (Cindy Rose Photography) |

Bruce Hall ’46

Vintner and farmer

Bruce Hall ’46 has taken the role of gentleman farmer and expanded it into a highly successful business. Willamette Farms, located in Newberg, Ore., sells hazelnuts, apples, Christmas trees — and wine.

Hall, whose ancestors traveled West on the Oregon Trail, chose to go to law school rather than follow his father in the timber business. Although he practiced law for 50 years, as a federal-court trial attorney, he also owned a tree farm before he purchased a farm on the Willamette River in 1959 that has since grown to 215 acres, and began selling hazelnuts and produce. In 2001, Hall decided to produce his own wine and planted the first grapes. The farm’s wines, which are marketed under the label “Vercingetorix,” or “VX” for short, first were sold two years later. Willamette Farms currently sells both pinot noir and pinot gris (sometimes known as pinot grigio). Its 2004 pinot gris received a rating of 88 from Wine Spectator.

What is the difference between a $15 bottle of wine and a $50 bottle?

As far as we’re concerned, a lot of people selling cheaper wines are blending different types of grapes. Our wines are all estate grown — the wine comes from where it says it comes from. Fifteen dollars is cheap for a pinot noir. There’s a lot of snobbery in wine, but there is an economic basis for it.

What is the biggest mistake that people make in choosing a wine?

The biggest mistake is to go into the equivalent of a grocery store and figure you’ll find a wine you’ll like. It’s like going in blindfolded. If you go to a good wine shop, they’re going to assist you. They’ll figure in your pocketbook and give you the benefit of their experience and knowledge.

What is the next trend in wines?

If you’re following Wine Spectator, they’re going to chart out the new regions rather than new types of grape. Eastern Washington, for example, is developing varietals we don’t get in western Oregon. The main thing is that wine is advancing all over the world.

Is it all right to order a full-bodied red wine if I’m having fish?

My opinion is that a pinot noir goes knockout well with some fish. Try some Coho salmon with our pinot noir. That’s as good as it gets.

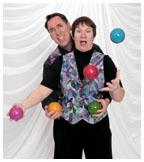

Jay Cady ’78 and his wife, Leslie, doing a typical day’s work. The hardest thing they’ve juggled? Cotton candy. (Alpha Omega Photography) |

Jay Cady ’78

Juggler and magician

In a house stocked with juggling clubs, spinning plates, Chinese yo-yos, unicycles, and magicians’ props, even the living room can be an impromptu performance space. “As you wander by, talking about what to get at the grocery store, you can pick up three clubs and juggle,” says Jay Cady ’78, who has been a professional juggler and magician for nearly three decades.

Cady took up juggling at Princeton after seeing Penn Jillette (of Penn & Teller fame) perform with a group called the Asparagus Valley Cultural Society. He bought a book and three rubber balls, and proved to be a quick study. A few years after graduation, Cady hooked on with a traveling juggling show where he met his future wife, Leslie. During one slow summer, Jay and Leslie started a street-performing show to make a little extra money; “romance ensued,” he says, and they have been together ever since. The Cadys perform educational shows that aim to get kids interested in math, science, and civics at schools and libraries in and around Kansas City. In their civics lesson, for instance, Cady juggles three clubs representing the three branches of government while quizzing students about each branch. At the end of the routine, he interlocks the three clubs and gently stands the triangular arrangement on top of his head in a memorable illustration of checks and balances.

What does it take to juggle?

Almost everyone has enough dexterity to learn how to juggle. It’s more a matter of perseverance and good instruction.

What’s the most difficult thing you ever tried to juggle?

We used to do a routine where I would invite the audience to give me objects to try to juggle, and cotton candy was the one that really just didn’t work well.

Because of the weight?

Well, that, and it sticks to your hands. With that routine, we also planted somebody with a bowling ball in the audience, and I remember I had the bowling ball, cotton candy, and some keys. On the first or second throw, the cotton candy went up and stuck straight on top of the bowling ball. That was the climax of the act.

After 30 years of juggling, what tricks are still difficult for you?

Juggling five balls. I can do it, but it’s hard. There are tricks that look hard and aren’t that hard. We like those. Some of it is just from familiarity. There’s a ball-juggling routine where [Leslie and I] steal the balls back and forth from each other, and the timing is very tight. But we’ve been doing it for so long, so many times, that we could do it at our funeral.

Majka Burhardt ’99

Professional climber

Is Ethiopia the next must-see destination in adventure travel? Professional mountain climber Majka Burhardt ’99 plans to find out. Burhardt, who also works as a freelance writer, was in the once-famine-stricken country last year to write a story about Ethiopia’s growing coffee trade. She met a British climber who had established two climbing routes in northern Ethiopia and showed her pictures of the terrain — “600-foot towers that no one’s ever touched,” Burhardt says. She soon began making plans to bring two partners back to the region to climb some of the unexplored sandstone faces.

Burhardt grew up in the relative flatlands of Minnesota, but after she took a summer climbing course at age 15, she was hooked on life in the mountains. Now, climbing is Burhardt’s world, professionally speaking, with her work split into three occupations: climber, writer, and guide. Foundations and gear companies support her climbing excursions, magazines pay her to write about her trips and other stories she encounters, and when she returns home to Colorado, private clients hire her to lead them through challenging climbs in the Rockies.

What is more difficult: climbing up a mountain or coming back down?

For me, climbing up is always the most fun, and coming down requires the most attention. Sometimes you are lucky and can hike down the backside of a vertical cliff. Other times you have to do a series of complicated rappels and down-climbing through technical terrain.

Which muscle groups are most important for a climber?

The big misconception is that climbers need strong arms. Your legs get you up a climb — from a sheer muscle-mass point of view, your quads, hamstrings, glutes, and calves are much bigger, and thus have more juice to burn, than your arms and shoulders.

Is there a reason why climbing ropes and gear tend to be brightly colored, or is that just the style?

Climbing gear comes in different colors so that you can easily sort through the multitude of sizes for each type of protection you put in the rock on your way up the cliff. Each company has its own color scheme, so if you use a variety of gear, which most of us do, you tend to look like a vertical rainbow.

What makes Ethiopia so interesting for a climber?

It’s sandstone, and really hard sandstone is amazing to climb.

There are these cracks — we call them “splitter cracks”

because they split a face — and it’s this perfect line. You

shove your hand and your toes and your fist and sometimes your head in

the cracks to figure out how to get up them. It’s about the purest

crack-climbing that you can get. ... I almost have to pinch myself. There

are these beautiful towering pieces of sandstone. You have to say, “How

do I get up there? How do I link all these cracks together?” The

adventure element of it is pretty supreme. ![]()

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.

Brett Tomlinson is an associate editor at PAW.