|

March 21, 2007: Features

Photo illustration, and photographs by Ricardo Barros

Woody Allen’s papers. This manuscript, titled “Life in the Future,” was later renamed “Sleeper.”

Gypsy Rose Lee’s manuscript of “The G-String Murders”

Bell from David Livingstone’s steamer, Pioneer

Woodrow Wilson’s pince-nez eyeglasses

Thomas Jefferson’s silver punch ladle

Charles Dickens’ desk lamps

Letter from Vice Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy to Lady Hamilton, Lord Nelson’s mistress

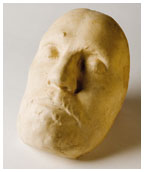

Oliver Cromwell’s death mask

Lock of Napolean Bonaparte’s hair

John J. Audubon’s shotgun

Lewis Carroll’s wallet

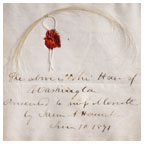

Strands of George Washington’s hair

Robert Lansing’s sketches of Arthur Balfour and the Persian foreign minister. (Princeton University Archives) |

Treasures

in Princeton’s attic

Amid the books and manuscripts,

Princeton’s libraries hold Charles Dickens’ desk lamps, John

J. Audubon’s shotgun, and Katherine Cornell’s bra

By Mark F. Bernstein ’83

What did they open, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s keys?

They were found in a leather pouch, sitting on the desk of his Hollywood bungalow the day he died in 1940. Some are long and some are short, some round and some thin. A couple of the keys look like they might open a door, others a trunk or a diary. None unlocks the mystery of what they actually are.

We know that they were donated to Princeton by Fitzgerald ’17’s daughter, Scottie Fitzgerald Lanahan, in the late 1940s, and comprise a small part of the University’s much larger Fitzgerald collection, which includes Fitzgerald’s papers and those of his wife, Zelda (a collection that keeps growing — Princeton recently received one of Zelda’s jackets). Another set of keys in the recesses of Firestone Library has a more certain use: The keys opened Thomas Jefferson’s wine cellar at Monticello, and were donated in 1944.

Why are these items important? In a sense, they aren’t, really. Most of the items — which generally are available to view, though curators strongly suggest calling in advance — are not tied to particularly famous events, but they do enjoy a provenance of having once belonged to famous people. Still, they are fascinating, the sort of curiosities one stumbles upon in a grandmother’s attic, cherished relics long forgotten, yet possessed of an undeniable charm and piquancy. The manuscripts division of Firestone and the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library serve, in a sense, as Princeton’s attic, holding, among millions of other items, some of the detritus of history.

“We don’t solicit objects, but they occasionally come to us,” says Don Skemer, the University’s curator of manuscripts. “Sometimes, though, when we get collections [of papers], objects come with them.” Last year, for example, when the University acquired the papers of the late Frederick Morgan ’43, one of the founders of the Hudson Review literary magazine, the archives of the Morgan family business, Enoch Morgan Sons’ Co., came along. Those included several bars of Sapolio soap, which were manufactured between 1869 and 1932. (The soap has some minor historical importance, Skemer says, because the Morgan company was innovative in marketing and employed prominent artists and writers to advertise its products.)

Our knowledge about many of these items is fragmentary — as in the case of Fitzgerald’s keys, we may know their provenance but not their use. Older items, acquired in the 19th and early 20th centuries, may have even less information — often just a bare index card stating a description of the item, the name of the donor, and the date of acquisition. Years ago, the library lacked the curatorial staff it now has to conduct deeper research. “When we get papers today, there is a deed of gift” that usually gives some details of the item’s provenance, Skemer explains. “But if it was here a hundred years ago, lots of luck.”

It is not surprising that a major research university should hold important manuscripts and archives, and Princeton is the repository of the personal papers of hundreds of famous people and organizations, ranging from Fitzgerald to Adlai Stevenson ’22 to the American Civil Liberties Union. In many cases, the subject had some personal connection to Princeton. There are, however, some exceptions. Woody Allen is a big one.

Allen, who attended New York University and City College of New York without graduating, had no personal ties to Princeton and so would seem an unlikely candidate to leave his papers at the University. For that, it seems we can thank a very unexpected source: Laurance Rockefeller ’32. According to a 1980 letter written to Richard Ludwig, a Princeton English professor and former associate University librarian for rare books and special collections, Allen explained: “When the idea of donating my papers to a university came up, Princeton was immediately thought of because of the very kind interest of the school and of Mr. Lawrence [sic] Rockefeller in once or twice asking me to come and record something or other, which I was not able to do. The thought that my papers, disorganized though they are, might serve some useful purpose, fills me with delight.”

If the papers were at one time disorganized, they are now carefully filed and preserved and include original manuscripts of many of Allen’s plays and movie scripts (Bananas, Annie Hall, Manhattan, and Hannah and Her Sisters among them) which show evidence of his revisions and marginal notes. The papers have come to Princeton in several batches over the years, Skemer says, but whether more might be forthcoming is not known.

The origin of Rockefeller’s relationship with Allen is also not known — Allen’s correspondence sheds no light on the question — but he certainly was an admirer. “Mr. Rockefeller was such a fan [of Woody Allen],” says Liz Halperin, secretary to Rockefeller’s son, Laurance, husband of Wendy Gordon ’79. “He thought he was a genius. He loved his movies.” So much so, it seems, that Rockefeller was a regular at Michael’s Pub in Greenwich Village, where Allen played clarinet in a jazz band on Monday evenings. Two years after Allen began donating his papers to Princeton, Rockefeller allowed Allen to film a portion of A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy at the Rockefeller family estate in Pocantico Hills, N.Y.

Gypsy Rose Lee, the famous stripper and subject of the eponymous Broadway musical Gypsy, didn’t go to Princeton, either. But perhaps few know that Lee (born Rose Louise Hovick) also was a novelist. Proof of her literary attainments exists in a typewritten manuscript of a novel she co-wrote, published in 1941, and titled, appropriately enough, The G-String Murders (it was later made into a movie called Lady of Burlesque, starring Barbara Stanwyck). According to the book’s dust jacket, which touts the author’s “native mascara language,” Lee boasted that she wrote the book “three times, with a thesaurus.”

That may be false modesty, suggests Maria DiBattista, a Princeton professor of English and comparative literature and chair of the Committee for Film Studies. DiBattista has written a review for Modernism/modernity magazine of the newly republished edition of The G-String Murders. Contrary to type, Lee was “a real reader” who took writing “rather seriously,” DiBattista says in an interview, adding that Lee was one of the few strippers then (or now, for that matter) who also wrote lyrics for the songs she sang in her acts. Lee began writing the novel while sharing a house in Brooklyn with an unlikely assortment of literary types including writer Carson McCullers, composer Benjamin Britten, and poet W.H. Auden. “She might have brought a little more bourgeois domesticity than they were used to because they were rather bohemian,” DiBattista adds dryly.

Along with the manuscript are a few pieces of correspondence (some signed “Gyp”) to Lee’s publisher. In one, she writes of hoping to stay in Chicago for a while “and get this publishing business off my mind. It’s like being all made up, ready to go on ... and not knowing what theater you’re playing.” The novel did well enough commercially that Lee wrote another whodunit (which is not in Princeton’s collection) titled Mother Finds A Body.

The G-String Murders manuscript was a gift by Gypsy herself on Sept. 3, 1942, but why the famous stripper chose Princeton, Skemer and DiBattista say, is another mystery. One possibility, though it is only speculation, is that the political-activist children of German novelist Thomas Mann, who were among Lee’s housemates in Brooklyn, had something to do with it. Mann himself taught at Princeton from 1938 to 1940.

Information about some items in the University’s collections is particularly spare, but we may use our imaginations to fill the gaps. Charles Dickens’ set of desk lamps, two brass candlesticks with glass chimneys engraved with the initials “C.D.,” is one such item. Stare at the lamps and you can see Dickens’ pen scratching away at David Copperfield or A Tale of Two Cities by the glow of their dim, yellow light.

A bronze bell that once clanged a warning on David Livingstone’s steamer, Pioneer, as it plied the Zambezi River still delivers a warm gong sound when it is moved. Livingstone, a Scottish missionary whose motto was “Christianity, Commerce, and Civilization,” was the first European to see Victoria Falls or explore parts of eastern Africa. From 1858 to 1864, he explored the Zambezi on the Pioneer, convinced that it was the best route to lead Christian missionaries into the African interior. (It wasn’t; the river is unnavigable in parts.) In 1865, he set off to find the source of the Nile and disappeared for six years, spending much of the time alone and sick. In 1869, the New York Herald sent journalist Henry Morton Stanley off to find him, which he did two years later, greeting him with the famous salutation, “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

Occasionally, with a few of the items in Princeton’s collections, there is very little to go on. The University owns John J. Audubon’s shotgun, a beautiful, heavy piece with a wooden stock and silver trim and hammer, engraved on top: “John James Audubon, Citizen.” Nothing more is known about it or its acquisition. Audubon, whose Birds of North America, a collection of 435 paintings, was a landmark event in American naturalism, observed his subjects closely but had to shoot and mount them so that he could capture them in detail for his books. Audubon reportedly used very fine shot so as not to damage his specimens, some of which may well have been sighted down the barrel of this gun.

Although the Founding Fathers often are portrayed as stiff and wooden, Thomas Jefferson, at least, was a passionate man who played the fiddle, danced, and was quite a wine connoisseur (as evidenced by the keys to his cellar). Another clue suggesting that the author of the Declaration of Independence enjoyed himself at a party is a silver punch ladle, engraved on the haft with his name and the year 1791, a time when he served as secretary of state. The ladle has an even richer historical pedigree in that it later belonged to President Grover Cleveland. (Apparently no one thought to count the White House silver when Cleveland left office.) In retirement, Cleveland moved to Princeton and became a University trustee. The ladle was donated in 1922 by his son, Richard Cleveland ’19.

There are not many pieces of clothing in Princeton’s collections, but there are a few, such as Zelda Fitzgerald’s jacket. The library also boasts a fragment of a nightcap knitted by Martha Washington, a pair of Woodrow Wilson 1879’s pince-nez eyeglasses, donated by longtime Nassau Street jeweler M. LaVake, and a bra belonging to actress Katherine Cornell, whom The New Yorker’s literary critic, Alexander Woolcott, once called “The First Lady of the Theater.” The University awarded Cornell an honorary degree in 1948, one of the first it awarded to a woman. It seems that she made a gift in return.

For those left unimpressed by items that once belonged to famous people, there are a few items that were once actually part of famous people. Thin strands of George Washington’s fine, sandy-white hair are tied with a piece of thread and affixed to a piece of paper with sealing wax. Another small picture frame contains a lock of Napoleon Bonaparte’s coarse, dark hair, taken at his death, along with a piece of a shroud that covered his coffin during his funeral in exile on St. Helena in 1821. The items were presented “Pour L’aimable Madlle. Emilie” by Francesco Antommarchi, Napoleon’s personal physician on St. Helena, dated Jan. 13, 1837, and were donated to Princeton in 1974 by W.C. Moore ’26. The University has a broader Napoleon collection that includes several of his letters and a signed decree divorcing him from his wife, Josephine.

Napoleon is not the only dictator whose things have found their way to Princeton. The University also holds a small collection of Adolf Hitler memorabilia, some of which was purchased from a dealer, Skemer says, and some of which was collected during World War II by Harry A. Brooks ’35, who died in 2001, two years after giving the items to Princeton. The collection includes letters to and from the Führer, photocopies of Hitler’s will and of documents relating to his marriage to Eva Braun, Nazi armbands, Third Reich postage stamps, and a few passports for high-ranking Nazi party members. An especially chilling item is a set of three photograph albums prepared for Herman Göring, Hitler’s second-in-command, by German zoologist Lutz Heck. Perhaps assembled in order to ingratiate himself with high Nazi officials, the albums contain 183 black-and-white photographs of a smiling Göring at various hunting lodges (he also served as the Reich’s commissioner of forests and woods), often surrounded by tail-wagging dogs. Elsewhere in Firestone sit two boxes of Wehrmacht toy soldiers, the sort of thing young German children must have played with during World War II, a joint gift by Caron Cadle ’79 and the Class of 1939 Foundation.

Death figures prominently among Princeton’s library oddities. The Laurence Hutton Life and Death Mask Collection in Firestone Library is perhaps the largest and most impressive collection of such masks in the world. These are plaster casts of the faces of famous people — a few, such as Abraham Lincoln’s, taken during life but most taken after death. Princeton has more than 100 of the masks (many are copies of originals located elsewhere), ranging from Frederick the Great to William Shakespeare to Daniel Webster, as well as a cast of Robert Burns’ skull.

In this instance, we know exactly how Princeton acquired the collection. Hutton, a lecturer in English literature at Princeton and later literary editor of Harper’s magazine, was a collector of literary memorabilia. In 1860, while Hutton was browsing in a New York bookstore, a boy came in with a death mask of Benjamin Franklin, which he said he had found in a pile of junk around the corner. Hutton investigated and found five more masks, which became the basis for his collection. He gave them to Princeton in 1897 along with a trove of other materials, including 61 Mark Twain letters.

The masks capture perfectly three-dimensional likenesses of ancient heroes and villains. Oliver Cromwell, for example, looks stern and resolute, very much the no-nonsense Lord Protector of England. One can see the outline of his goatee, as well as a large blemish on his forehead — history preserved, literally, warts and all. A mask of Henry IV of France was made in 1797, almost 200 years after the king’s death. Workers who were renovating the royal tombs at Saint-Denis discovered his body in almost perfectly preserved condition, and could not resist the urge to capture him for posterity.

A letter to Emma, Lady Hamilton, Lord Horatio Nelson’s mistress, written to her by Vice Admiral Sir Thomas Hardy after Nelson’s death at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, and now at Princeton, provides some touching details. Hardy promises to pass along Nelson’s personal effects, including a lock of hair, rings, breastpins, “and all your Ladyship’s pictures.” But Hardy tries to dissuade Lady Hamilton from meeting the corpse upon its return to England. “As his dear body is in spirits, I think, it would be wrong for you to think of seeing him, and do let me beg of you to give up the idea.” Overcome with grief and lacking legal status as Nelson’s wife, she was barred from both meeting his body and attending his funeral.

Although he does not mention it in this letter, Hardy had found on Nelson’s desk a last letter to his mistress, pledging his undying love, which Hardy also delivered. Lady Hamilton’s remaining years, however, were tragic. Nelson had asked the British government to look after her, but his wishes were ignored. She soon found herself penniless, spent a year in debtor’s prison, and drank herself to death less than 10 years after Nelson died.

Other items provide a small window into the owner’s soul. Lewis Carroll was the nom de plume of the Rev. Charles L. Dodgson, who wrote Through the Looking Glass and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. A trained clergyman, mathematician, and logician, as well as a writer and photographer, Dodgson seemed possessed of a split personality. On the one hand, there was the Dodgson who suffered from a lifelong stutter and showed a passion for order, as is evidenced by his wallet — a sturdy leather pouch, the pockets of which are meticulously labeled for what was to go in them: stamps, envelopes, stamped envelopes, postcards, and scrap paper. That Dodgson was quite unlike the more whimsical Lewis Carroll who wrote the delightful nonsense poem, Jabberwocky.

The Carroll wallet is part of the large Morris L. Parrish Collection of Victorian Novelists, which includes manuscripts, photographs, letters, and other items amassed by Parrish, who attended Princeton briefly with the Class of 1888. Princeton awarded him an honorary master of arts degree in 1939, largely because of his impressive literary collection, and upon his death in 1944, he bequeathed his entire library, including furniture, to Princeton. (Today, the furnishings are in the Parrish Room, a re-creation of Parrish’s library that is found in the Rare Books and Special Collections Department in Firestone Library.)

Although all of the above items are located in Firestone, the Mudd Library also contains a few curiosities. Among the most peculiar are 58 pencil doodles drawn by Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of state, Robert Lansing, at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Wilson had little use for the lawyerly Lansing, and preferred to act as his own foreign minister. “Everything Mr. L does seems to irritate him,” Edith Wilson’s secretary noted in her diary during the peace conference. Edith, for her part, shared her husband’s feelings. “I hate Lansing,” she once remarked, and helped push him out of the Cabinet in February 1920, shortly after Wilson’s stroke.

So it is not surprising that Lansing, with relatively little to do in Paris, resorted to drawing pictures of the figures he encountered there, on stationery of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace. The sketches are not dated and most of the subjects are not identified, although the collection does contain likenesses of British foreign minister Arthur Balfour (“in a characteristic doze,” as Mudd Library’s online finding aid puts it) and American labor leader Samuel Gompers.

If Lansing ever drew any cartoons of his boss, he must have had the

good sense to destroy them. ![]()

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.