January 23, 2008: Books and Arts

Rereading the Social Gospel

Paul Raushenbush edits a book that launched a movement a century ago

For a complete list of books received, click here.

Paul Raushenbush, associate dean of religious life, is the great-grandson of Walter Rauschenbusch, whose 1907 book inspired the Christian social-justice movement. (Marylu Raushenbush) |

Rereading

the Social Gospel

Paul Raushenbush edits a book that launched a movement a century

ago

By Deborah Yaffe

In 1886, the young Baptist preacher Walter Rauschenbusch embarked on a harrowing 11-year ministry on the edge of the impoverished Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood of New York City. The job undermined his health — his grueling workload brought on an illness that worsened his growing deafness — but it also inspired Christianity and the Social Crisis, the book that helped launch the Christian social-justice movement known as the Social Gospel.

“This book was born out of an intense encounter with poverty,” says Paul Raushenbush, Princeton’s associate dean of religious life and Walter Rauschenbusch’s great-grandson. “People around you are dying because of the incredible suffering that the system around them is enforcing, and you have to go back and say, well, what does the Bible say about that?”

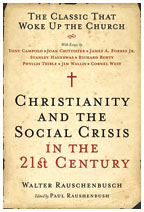

To

mark the book’s 100th anniversary, Raushenbush, a Baptist minister,

has edited a new edition, Christianity and the Social Crisis in the

21st Century: The Classic That Woke Up the Church, published by HarperOne

last summer. The reissue pairs the original 1907 text with commentary

by eight contemporary thinkers, including Cornel West *80, the Class of

1943 University Professor in the Center for African American Studies at

Princeton.

To

mark the book’s 100th anniversary, Raushenbush, a Baptist minister,

has edited a new edition, Christianity and the Social Crisis in the

21st Century: The Classic That Woke Up the Church, published by HarperOne

last summer. The reissue pairs the original 1907 text with commentary

by eight contemporary thinkers, including Cornel West *80, the Class of

1943 University Professor in the Center for African American Studies at

Princeton.

The original version was a hot seller in its day, inspiring later generations of mainline Protestants to embrace liberal reforms, from abolishing child labor to ending racial segregation. With the religious right now politically influential, Paul Raushenbush (the family Americanized its name after World War I) says he wanted his great-grandfather’s ideas “reintroduced into the public conversation about the role of religion.”

Walter Rauschenbusch argued that Jesus was a revolutionary thinker whose promised “kingdom of God” must be realized not only in heaven but also here on earth, through more egalitarian social relations. The conditions in early 20th-century American cities — overcrowded tenements, dangerous factories, polluted air — demanded a political response from Christians who took their faith seriously, Rauschenbusch insisted.

For the new volume, Paul Raushenbush chose commentators whose work draws on the Social Gospel tradition, including evangelicals Tony Campolo and Jim Wallis; theologian Stanley Hauerwas; and the philosopher Richard Rorty, a grandson of Walter Rauschenbusch and cousin of Paul Raushenbush who died in June.

While praising Rauschenbusch for his idealism and commitment to social justice, the contributors also note troubling currents in his thought: his denigration of Judaism and Catholicism, his racial insensitivity, and his Victorian attitudes toward women. Over the years, more conservative critics have called Rauschenbusch’s theology little more than prettified Marxism, lacking Christianity’s conceptions of sin, atonement, and redemption.

“Rauschenbusch’s gospel had little need of a savior. It merely displaced the problem of evil — the supreme tragedy of the human soul in rebellion against God — with the challenge of social iniquities,” journalist Joseph Loconte wrote last May in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, one of several prominent articles inspired by the new edition. “It is hard to see ... how Rauschenbusch’s theology could be called Christian in any meaningful sense of the term.”

Although Paul Raushenbush, the first of Walter Rauschenbusch’s descendants to follow him into the ministry, acknowledges the datedness of some of his great-grandfather’s social attitudes, he disagrees with such theological critiques. “Sin is actually something that’s ingrained in the structure of society, and so sin is something that an entire community can repent of,” Raushenbush says. “If we have so structured our society to benefit a few at the expense of the many and the powerful at the expense of the weak, then that is a structural sin.”

Raushenbush says he’s surprised by how personally he’s taking the criticism. After all, he was born nearly 50 years after Walter Rauschenbusch’s death and grew up knowing his illustrious ancestor mostly as the author of a prayer the family read on Thanksgiving.

The controversy proves that these century-old ideas still stir powerful emotions, Raushenbush says.

“Of course The Wall Street Journal hates this book. No surprise

there,” he says. “The Wall Street Journal serves a master

that this book does not serve.” ![]()

Deborah Yaffe is a writer in Princeton Junction, N.J., and the author of Other People’s Children: The Battle for Justice and Equality in New Jersey’s Schools (Rutgers University Press).

For a complete list of books received, click here.

Swimming

in a Sea of Death: A Son’s Memoir — David Rieff ’78

(Simon and Schuster). In this personal account, the author, the son of

the writer Susan Sontag, recounts his mother’s final battle with

cancer and what it was like for him to watch her die as she struggled

with her own fear and denial of death. Rieff also explores the role and

professional lives of cancer physicians, and how they deal with terminally

ill patients. Rieff is a contributing writer to The New York Times

and the author of seven other books.

Swimming

in a Sea of Death: A Son’s Memoir — David Rieff ’78

(Simon and Schuster). In this personal account, the author, the son of

the writer Susan Sontag, recounts his mother’s final battle with

cancer and what it was like for him to watch her die as she struggled

with her own fear and denial of death. Rieff also explores the role and

professional lives of cancer physicians, and how they deal with terminally

ill patients. Rieff is a contributing writer to The New York Times

and the author of seven other books.

Before the

Glory: 20 Baseball Heroes Talk About Growing Up and Turning Hard Times

Into Home Runs — Billy Staples and Rich Herschlag ’84

(HCI). The authors interviewed baseball greats — including Ron LeFlore,

who spent time in prison before playing for the Detroit Tigers in the

1970s — about their childhoods and struggles with poverty, drugs,

and health issues. Each chapter includes a lengthy interview and a profile

of a player. Staples is an English teacher in Bethlehem, Pa. Herschlag

runs a consulting business, Turnkey Structural, in Easton, Pa.

Before the

Glory: 20 Baseball Heroes Talk About Growing Up and Turning Hard Times

Into Home Runs — Billy Staples and Rich Herschlag ’84

(HCI). The authors interviewed baseball greats — including Ron LeFlore,

who spent time in prison before playing for the Detroit Tigers in the

1970s — about their childhoods and struggles with poverty, drugs,

and health issues. Each chapter includes a lengthy interview and a profile

of a player. Staples is an English teacher in Bethlehem, Pa. Herschlag

runs a consulting business, Turnkey Structural, in Easton, Pa.

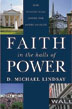

Faith in the

Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite —

D. Michael Lindsay *06 (Oxford). Based on interviews with 360 leaders

in government, academia, the entertainment business, and the business

world, Lindsay’s study looks at the rise of evangelicals and their

Christian influence. A New York Observer reviewer called the book “a

provocative study” but criticized the author’s accepting “unquestioningly

the movement leaders’ self-interested pronouncements.” Lindsay

is an assistant professor of sociology at Rice University.

Faith in the

Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite —

D. Michael Lindsay *06 (Oxford). Based on interviews with 360 leaders

in government, academia, the entertainment business, and the business

world, Lindsay’s study looks at the rise of evangelicals and their

Christian influence. A New York Observer reviewer called the book “a

provocative study” but criticized the author’s accepting “unquestioningly

the movement leaders’ self-interested pronouncements.” Lindsay

is an assistant professor of sociology at Rice University.

![]()

For a complete list of books received, click here.

Albee

on Albee

Playwright Edward Albee shares his know-how of drama and dramatists

with Princeton students

Edward Albee’s new play, “Me, Myself and I,” will run through Feb. 17 at the Berlind Theatre in the McCarter Theatre Center. (Sara Krulwich/The New York Times Sara Krulwich/The New York Times) |

Playwrights love to talk about their characters, but can grow reticent when it comes to delving into the working of their own minds. “If you talk too much about the [creative] process, you’re paralyzed,” said Edward Albee, the Pulitzer Prize-and Tony Award-winning author of works such as The Zoo Story, A Delicate Balance, and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. “There has to be a kind of magic about it.”

Nevertheless, Albee talked quite a lot about himself and his work in a course offered in the fall by the Program in Theater and Dance in the Lewis Center for the Arts. The course was titled “Albee on Albee,” and that is just what it was. Ten students, chosen by application, met weekly with Michael Cadden, a senior lecturer and the program’s director, to study the works of the man pronounced by many as America’s greatest living playwright. Three times during the semester they were graced by Albee himself, who in his first class session led a free-wheeling discussion of drama and dramatists. At the end of the semester, the students were scheduled to watch Albee in action as he oversaw rehears-als of a new play, Me, Myself and I, a comedy about identical twin brothers — both named Otto — which runs through Feb. 17 at the Berlind Theatre at McCarter Theatre Center.

Albee warned students, who read a biography of him, against the temptation to engage in literary psychoanalysis. “Many people make the mistake of thinking that plays are autobiographies,” he said. “This is nonsense. I have never written a play that is based on experiences I have had.” He also distinguished between the freedom of the stage and the restraint of film. In a play, Albee said, audience members can look wherever on the stage they choose. But in a movie, “I am told what I must look at, what I am supposed to feel,” he said.

In addition to dropping some show-business nuggets (he wanted James Mason and Bette Davis for the leads in the film version of Virginia Woolf but had to settle for Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor), Albee questioned the students closely about their backgrounds, interests, and reasons for taking the course. When a few admitted to writing fiction as well as plays, Albee counseled that it is the rare writer who can write well in more than one genre. “Arthur Miller wrote one novel,” he joked. “Don’t read it.”

Plays are meant to be read as well as performed, and are underappreciated as literature, said Albee, the author of more than 30 plays. Nevertheless, a playwright must never lose sight of his play as a dramatic work. “If you’re writing a play, you must see and hear everything you put down — as a play performed on stage, not as some ephemeral reality. This will save you an awful lot of trouble.” Even so, the effort is doomed to at least some disappointment. “The performance is always an approximation: it cannot, axiomatically, be as good or as accurate as what you heard in your head when you were writing.”

Now 79, Albee insists that age has not changed his perspective on character. A playwright should be able to write characters that are 90 when he is 18 and characters that are 18 when he is 90, he said. It is the playwright’s vision that must predominate, not the actors’ or the director’s. That is why he insists on sitting in on rehearsals for his plays and writes copious stage directions, comparing them to notations a composer puts in a musical score. When a student asked if he has become less demanding as he has grown older, Albee seemed to take offense. “Why,” he wanted to know, “should I become less demanding?”

He doesn’t hesitate to celebrate the playwright’s importance, and illustrated this point with a story. Before a rehearsal for Virginia Woolf, producer Richard Barr ’38 told him to look around the theater. It was filled with actors, understudies, agents, props people, lighting assistants, stage managers, lawyers — all for a three-act play with only four characters. Why are all these people here? Barr asked rhetorically. Because you wrote a play.

“Never lose sight of that,” Albee told his students. “They

are there because you did something. So don’t take anyone’s

advice if it’s not good for the work.” ![]()

By M.F.B.

Courtesy Silas Kopf ’72 |

For the bathroom stall, above, titled “Is that You, Senator?”

furniture maker and marquetry artist Silas Kopf ’72 asked people

to send him ideas for graffiti to include on the inside doors, sending

out a mass e-mail through Princeton’s TigerNet discussion groups.

After receiving dozens of statements and questions, including “Who

needs rhetorical questions?” he asked visitors to his Easthampton,

Mass., studio to pick out a line or two and add to the door in their own

handwriting. Kopf made a man’s feet in marquetry – the craft

of piecing together different materials to make a design — using

inlaid natural woods. Kopf is a leading practitioner of marquetry and

inlay in America. “Is that You, Senator?” was part of a solo

exhibition of his furniture at Gallery Henoch in New York from Nov. 15

through Dec. 8. ![]()