|

March 5, 2008: Letters

![]() PAW

Letter Box Online

PAW

Letter Box Online

PAW has expanded its

Web site to include a feature called Letter Box, where many more letters

than can fit in the print magazine are published. Please go to

Letter Box to read and respond.

PAW welcomes letters on its contents and topics related to Princeton University. We may edit them for length, accuracy, clarity, and civility; brevity is encouraged. Letters, articles, and photos submitted to PAW may be published or distributed in print, electronic, or other forms. Due to the volume of correspondence, we are unable to publish all letters received. Write to PAW, 194 Nassau St., Suite 38, Princeton, NJ 08542; send e-mail to paw@princeton.edu

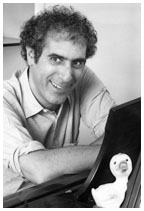

Jeff Moss ’63 |

My husband, Jeff Moss ’63, wrote a thoroughly moving and beautifully melodic song entitled “The Song Goes On.” Unfortunately, the lyric was misquoted in the excellent article in your special issue (Jan. 23) on “the most influential Princeton alumni ever.” The lyric of the song in its entirety is attached, and as you can see, it reads: “After the singer has gone, the song goes on” (not “after the singer has died”).

Jeff wrote the song specifically for the 100-year memorial service of the Triangle Club, and after he sang it on that lovely piano in the Chapel, he continued to play the music while different people softly recited the names of the members from years gone by who had died. It was hauntingly beautiful in that magical setting.

As is often correctly said, the children are the future, and I believe,

as do many, that Jeff was dedicated (as indeed are all the writers of

Sesame Street) to educating and thereby hopefully imbuing our future leaders

with knowledge, kindness, and humor — attributes that are often

overlooked in the scurry of life. It is for that reason that it was so

thoroughly rewarding to have him celebrated in such a way.

The Song Goes On

A song once was sung

By someone so young

A boy I remember

The day had begun

A bright orange sun

In early September

Now time has flown by

And far in the sky

The sun sets bright as flame

A different voice is singing

But the song is still the same

The song goes on

The song goes on

After the singer has gone

The song goes on

The heart of the song

Can stay true and strong

The music keep ringing

If one voice falls still

Another voice will

Continue/soon join in the singing

The leaves turn to gold

The stories unfold

With memories to share

And different voices sing now

Still the song is always there

The song goes on

The song goes on

After the singer has gone

The song goes on

The music and rhyme

Are carried through time

From one to another

The melodies pass

Like wind through the grass

From sister to brother

And on any day

A boy on his way

May find the song and then

He’ll sing it for the first time

And the song is new again

The song goes on

The song goes on

After the singer has gone

The song goes on

The song goes on

The song goes on

After the singer has gone

Still the song goes on

ANNE W. BOYLAN (MOSS)

Red Hook, N.Y.

I very much appreciated the report about the campus [distributed with the Jan. 23 PAW] and what we might expect over the next 10 years. By and large, I find it thoughtful, imaginative, and traditional. However, I have one suggestion: Put all parking underground, thereby increasing opportunities for green space, playing fields, and/or buildings.

CUTHBERT RUSSELL TRAIN ’64

Southwest Harbor, Maine

There’s only one thing missing from the new Princeton campus plan — a people overpass spanning Washington Road to the north of the planned Streicker Bridge. Its width should extend from a point near the rear corner of McCosh Hall to another down by the walkway from Frist, and Washington Road would need to be lowered, as much as 20 feet perhaps, from Ivy Lane to William Street. Traffic on the lowered Washington Road would no longer be able to make turns onto Prospect Avenue (which could be reconfigured, terminating with a small circle adjacent to Robertson Hall for U-turns).

The Washington Road overpass would bridge the pedestrian heart of the campus, permitting the free, safe, and continuous flow of students, professors, et al. As things now stand (no pun intended), countless minutes are wasted by people waiting for the light to turn green when they could be on their way to class.

This project is devoid of glamour, and no wealthy donor is likely to embrace it, but the benefits it would bring to the entire University community would be real.

C. THOMAS CORWIN ’62

Cold Spring, N.Y.

After reading “Thesis envy” by Josh Kornbluth ’80 (Perspective, Dec. 12), I felt thoroughly entertained — and envious, to boot.

Like Josh, I began my senior year at Princeton with an academic record best described by his word, “mediocrity,” and no clue about the subject of my looming thesis. Unlike Josh, no one in authority suggested I could put my thesis and degree on hold until capping a creative career with a “transcendentally brilliant” autobiographical monologue worth current production in San Francisco, as well as belated graduation honors.

Truthfully, I dug my own hole nine months prior to developing all the symptoms of “Kornbluth panic” as my thesis deadline approached. I was in danger of failing a dreaded “major” course on the Middle Ages in spring 1946, so I claimed postwar stress before midterm and became a medical dropout.

Come fall, I faced the stressful prospect of needing high marks in two history courses and my thesis. Luckily, I had discovered Eric Goldman, a truly inspirational teacher and lecturer, who was responsible for piquing my fascination with modern American history, as my counterpart to Josh’s Sheldon Wolin. I aced a pair of Goldman’s courses that year, raising the average in my major to the equivalent of a “gentleman’s C+” — enough to guarantee a degree, if my thesis proved acceptable.

My adviser, Robert “Boats” Albion, distinguished maritime historian, suggested that I choose between the Dardanelles Strait and Suez Canal as my subject. I opted for the former, figuring it would be easier to recount its significance in World War I than to project the canal’s pivotal post-World War II role.

During the winter of 1947, I suffered through the same pangs experienced 33 years later by Josh. I spent untold hours in the Firestone stacks seeking every reference to the Dardanelles ever recorded. By do-or-die time (spring break), possessing no typing skills, I was compelled to write a chapter a day in legible longhand in order for my stenographer to keep pace.

I feared that “Boats” would not be able to read it by the drop-dead date in May. But he managed, and he affixed not only an unforgettable appraisal — “Not enough virgin material” — but also a charitable, degree-saving B+.

ASA S. BUSHNELL III ’47

Tucson, Ariz.

Professors Frist and Reinhardt debate means to health care (cover story, Dec. 12). I propose that our government is obligated to provide health care to all without debate.

If, knowingly, one deprives a person of conditions necessary to support life, and causes death, one is charged with murder.

Hobbes characterizes a citizen’s position in relation to the state as equivalent to being taken by a press-gang onto a ship that sails. One can live within the resources and practices imposed by the captain, or jump overboard and drown. Citizens who are not captains of their own ships similarly must live within the conditions imposed by their state.

The Institute of Medicine estimates that 18,000 Americans with treatable conditions die annually because, without insurance, they lack access to medical care. Forty million to 47 million Americans live without health insurance. The United States, by not funding insurance costs for these uninsured, creates conditions responsible for their deaths.

Decisions of government and those elected not to provide health insurance to uninsured citizens are taken knowing that 1) financial resources are available; 2) 18,000 will die without insurance, and 3) those 18,000 have no options to “jump ship” for a country that provides health-care access. Just as an individual commits murder by depriving another of the essentials of life, the U.S. government, by not acting to provide adequate access to health care, murders the citizens we know die every day from lack of health care.

Murder on the part of government pre-empts discussion of the structure of health-care operations. The Princeton faculty can debate mechanisms, controls, and so forth to prepare the next generation of decision-makers; however, it is time to stop using debates over means to avoid discussing how government murders its citizens.

I suggest that we reword Professor Reinhardt’s statement of the situation in U.S. health care to read as follows: “In Canada and Germany the idea that somebody who is sick would die from lack of access to health care is extremely repugnant, while in the U.S. it is extremely acceptable.” Is this a nation for Princeton to serve or change?

ROBERT E. BECKER ’55, M.D.

Park City, Utah

As I read Steve Townend ’71’s Jan. 23 letter in response to Laura Vanderkam ’01’s Perspective essay (Oct. 24) about running while she was pregnant, I couldn’t help feeling that he was pointing the finger at me as well. Am I part of the “new breed of young mothers for whom children, not just after birth, but now prenatally too ... represent a bit of an inconvenience”? I exercised when I was pregnant; I kept my full-time job after Oscar was born; my husband and I (get this) sometimes leave him with a babysitter to have time to ourselves. I even felt “freed from my burdens” after I gave birth, because then I didn’t have to approach getting into bed as would a whale who was about to beach herself.

I continue to explore new hobbies and make time for the old ones. I respectfully submit this radical theory: It is dangerous for me to rely on only one other soul to provide complete and utter fulfillment in life, even if that soul is a sweet child. Fulfillment comes from creating new ideas, exploring the world, and carving out space and time to be my own person. I’m a better mother for it, and I suspect Laura is, too.

WINDI (LASSITER) PADIA ’00

Frederick, Colo.