March 19, 2008: Books and Arts

Shakespeare and an orange-seller

Playwright Roger Q. Mason ’08 prepares his play for Berlind

When poets and artists collaborate

For a complete list of books received, click here.

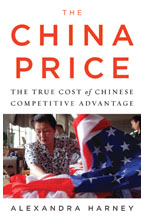

Alexandra Harney ’97 interviewed Chinese workers and factory managers for her book, “The China Price.” (Courtesy Penguin Press) |

Reading

Room

Cheap

goods at what cost?

Alexandra Harney ’97 examines the fallout of “the

China price”

By Iris Blasi ’03

Headlines last fall were full of news about recalls of Chinese products: lead-laden children’s toys; tainted pet food; toothpaste laced with diethylene glycol, a toxic chemical commonly used in antifreeze.

Those in the know were hardly shocked. Many Chinese manufacturers regularly take extreme measures — overworking laborers, using deadly chemicals, falsifying records to circumvent safety codes — to keep costs low. The time to pay the piper was due to hit sooner or later, as Alexandra Harney ’97, a Financial Times correspondent, explains in The China Price: The True Cost of Chinese Competitive Advantage.

To be published by Penguin later this month, the book explores how “the China price” has become “the lowest price possible.” Harney examines the costs — risks to public health and the environment, as well as economic and cultural repercussions — that these “bargains” exact from China and the world at large.

Always

fascinated by Asia, Harney studied Japanese in high school and wrote her

thesis for the Woodrow Wilson School on Japanese defense policy. After

graduation, she studied at Tokyo University, but abandoned academia when

offered a post as a Financial Times reporter. After four-and-a-half

years as a reporter in Tokyo and an editorial stint in London, Harney

was transferred to Hong Kong in 2003, where, on weekly trips to the mainland,

she witnessed firsthand the pressure factory managers were under to cut

costs and boost production.

Always

fascinated by Asia, Harney studied Japanese in high school and wrote her

thesis for the Woodrow Wilson School on Japanese defense policy. After

graduation, she studied at Tokyo University, but abandoned academia when

offered a post as a Financial Times reporter. After four-and-a-half

years as a reporter in Tokyo and an editorial stint in London, Harney

was transferred to Hong Kong in 2003, where, on weekly trips to the mainland,

she witnessed firsthand the pressure factory managers were under to cut

costs and boost production.

Harney decided to investigate, taking a temporary leave from journalism to accept a position at the University of Hong Kong. The move paid off: Approaching sources — both workers and managers — as an academic instead of a journalist earned her both trust and access.

Representatives that American companies send abroad often are shown dummy or model factories, but Harney saw the “one-star factories” (China’s “dirty open secret,” Harney says), where output is 20 to 30 percent higher than in the model factories because employees work much longer than the government-regulated workweek. Harney also spent time with people such as Tang Manzhen, who lost her 36-year-old husband, Deng, to silicosis, a lung disease caused by repeated inhalation of dust. He had worked grinding semiprecious stones at a jewelry factory.

Harney is quick to clarify: The China price is “not all bad,” she says. As industry grew rapidly to meet the world’s demand, millions of workers were lifted out of poverty. And yet, as Harney writes, “China has become a victim of its own success,” faced with the gargantuan task of cleaning up its environment and improving conditions for the estimated 200 million workers toiling in dangerous situations.

Change is on the horizon as workers increasingly unionize, Harney argues, and the minimum wage has been raised in some provinces. Ultimately, the country’s ability to shift from “provider” to “innovator” will determine its future path, she says.

“I hope the next time people buy something, they’ll look

at the label and think, ‘What’s the real price of my $5 T-shirt?’”

Harney says. ![]()

Iris Blasi ’03 is a writer and editor in New York City.

For a complete list of books received, click here.

“The Troubled Roar of the Waters”: Vermont in Flood

and Recovery, 1927--1931 — Deborah Pickman Clifford and

Nicholas R. Clifford ’52 (Univer-sity Press of New England). On

Nov. 2, 1927, New England was hit by one of its worst natural disasters,

and Vermont suffered the most damage. Using newspapers, personal journals,

and testimony, the authors tell the story of the flood, its victims, and

the recovery effort. Deborah Pickman Clifford is a New England historian.

Nicholas Clifford is a writer who taught history at Princeton, MIT, and

Middlebury.

“The Troubled Roar of the Waters”: Vermont in Flood

and Recovery, 1927--1931 — Deborah Pickman Clifford and

Nicholas R. Clifford ’52 (Univer-sity Press of New England). On

Nov. 2, 1927, New England was hit by one of its worst natural disasters,

and Vermont suffered the most damage. Using newspapers, personal journals,

and testimony, the authors tell the story of the flood, its victims, and

the recovery effort. Deborah Pickman Clifford is a New England historian.

Nicholas Clifford is a writer who taught history at Princeton, MIT, and

Middlebury.

Ask

for It: How Women Can Use the Power of Negotiation to Get What They Really

Want — Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever ’79 (Bantam

Books). A follow-up to their 2003 book, Women Don’t Ask, which found

that women are averse to negotiating for what they deserve, the authors’

new book offers a guide to asking effectively for a raise, a promotion,

or help at home. Babcock is an economics professor at Carnegie Mellon.

Laschever is a journalist in Concord, Mass.

Ask

for It: How Women Can Use the Power of Negotiation to Get What They Really

Want — Linda Babcock and Sara Laschever ’79 (Bantam

Books). A follow-up to their 2003 book, Women Don’t Ask, which found

that women are averse to negotiating for what they deserve, the authors’

new book offers a guide to asking effectively for a raise, a promotion,

or help at home. Babcock is an economics professor at Carnegie Mellon.

Laschever is a journalist in Concord, Mass.

Jihad

in Islamic History: Doctrines and Practice — Michael Bonner

*87 (Princeton University Press). This study looks at the early history

of “jihad” — a word that has different meanings to different

people. To some, it implies peace; to others, violence. The author argues

that jihad means more than either of these; he finds that jihad is a complex

set of doctrines and practices governing warfare and relationships between

Muslims and non-Muslims that has changed over time. Bonner is a professor

of medieval Islamic history at the University of Michigan.

Jihad

in Islamic History: Doctrines and Practice — Michael Bonner

*87 (Princeton University Press). This study looks at the early history

of “jihad” — a word that has different meanings to different

people. To some, it implies peace; to others, violence. The author argues

that jihad means more than either of these; he finds that jihad is a complex

set of doctrines and practices governing warfare and relationships between

Muslims and non-Muslims that has changed over time. Bonner is a professor

of medieval Islamic history at the University of Michigan. ![]()

By K.F.G.

(Courtesy Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library) |

The book at left, Illustrium Imagines (Images of the Illustrious), published

in Lyons, France, in 1524, is the earliest printed book to illustrate

ancient coins. It is among 250 items including rare books, coins, medals,

and manuscripts from the University Library’s Department of Rare

Books and Special Collections that are featured in an exhibition, “Numismatics

in the Renaissance,” at Firestone Library. Among the items on display

are coins and medals of the Renaissance and the ancient Greek and Roman

coins that inspired them; 15th- and 16th-century books about ancient coins;

and 16th-century drawings and prints of ancient sculpture from the Princeton

University Art Museum. The exhibit runs through July 20. ![]()

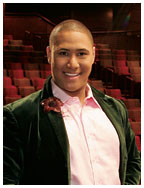

Roger Q. Mason ’08 is one of some 50 seniors whose theses are works of creative art, including novels, films, visual-arts exhibits, and musical compositions. (Beverly Schaefer)

For her creative thesis, Irene Lucio ’08, front, performed the title role in in Henrik Ibsen’s “Hedda Gabler.” (Frank Wojciechowski) |

Shakespeare

and an orange-seller

Playwright Roger Q. Mason ’08 prepares his play for Berlind

By Deborah Yaffe

For Roger Q. Mason ’08, the play that would become his senior thesis began with an image: In his mind’s eye, he saw a black woman offering an orange to a dying Shakespeare.

That seed, planted during a class discussion about the prostitutes who sold oranges to the patrons of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, germinated into Orange Woman, A Ballad for a Moor, which will run for five performances between April 4 and 12 at McCarter Theatre Center’s Berlind Theatre.

Mason based his protagonist on the real-life Lucy Negro, a black woman who ran a brothel in Elizabethan London’s red-light district. Like some scholars, Mason believes that Lucy Negro and Lucy Morgan, a dancer in Queen Elizabeth I’s court, were the same woman, and that this woman was the mysterious Dark Lady of Shake-speare’s sonnets.

Interweaving fact and fiction, Mason’s play chronicles Lucy’s estrangement from the queen, her relationships with Shakespeare and with a fictional Irish madam, and her acquisition of a house of prostitution. “What I’m doing,” says Mason, “is using drama to reimagine history, to rewrite it.”

In the two years since his first mind’s-eye glimpse of the orange woman, Mason has read extensively about Elizabethan prostitution and court life. He studied Shakespearean theater last summer at Oxford Univer-sity and took research trips to London, Dublin, and Stratford-on-Avon.

Although Mason has both produced and directed shows at Princeton, where he heads the student-run Black Arts Company: Drama, he put his fledgling script in the hands of a professional, Kemati Porter, a former McCarter producing associate who is directing the student cast. The production costs for Mason’s play, and for most other creative theses, come out of the budget of the Lewis Center for the Arts.

Mason, an English major who hopes to attend graduate school in playwriting, is one of at least 56 seniors whose theses are not traditional research papers but works of creative art — novels and poetry collections, films, exhibits, dance performances, theatrical productions, and musical compositions.

In February, comparative literature major Irene Lucio ’08 performed the title role in Ibsen’s play Hedda Gabler. At 185 Nassau St., the home of the Lewis Center, Lena Neufeld ’08 will exhibit black-and-white photographs she took at recreational-vehicle communities in three states for an ethnographic project melding her anthropology major with her visual-arts certificate. And John Fontein ’08, a music major earning a certificate in computer science, is writing a 10-minute electronic composition that the Princeton Laptop Orchestra will perform next month at a Chicago-area music festival.

“It’s great to focus all my work my senior year on the music that I’m passionate about,” Fontein says.

Indeed, for seniors who plan careers in the arts, producing creative theses with the support of professionals on and off the faculty offers an experience that student-led productions do not, says Mason’s faculty adviser, Robert Sandberg ’70, a playwright and a lecturer in English and in the theater and dance program. “It’s a much better test of what it’s really like to do it,” Sandberg says. “It’s not playing around.”

Mason first heard of the creative-thesis option during 2004’s

pre-frosh weekend when he attended a performance of Playing in the

Dark, the senior thesis of Khalil Sullivan ’04, now a graduate

student in English at the University of California, Berkeley. “To

see an African-American man have his original play produced on stage at

Princeton was really one of the deciding factors for me coming here,”

says Mason, whose father is African-American and mother is Filipino. “It

said, ‘This can be my world, too.’” ![]()

Deborah Yaffe is a writer in Princeton Junction, N.J.

The 1938 British picture book, “Orlando the Marmalade Cat,” will be among the rare books at a book-adoption party. Courtesy Cotsen Children’s Library |

Books need friends, too. And the Princeton University Library is hoping that bibliophiles who attend its first “book-adoption party” March 30 at Chancellor Green will donate funds to support the acquisition or preservation of rare books, manuscripts, maps, photographs, and coins in the University Library’s special collection. At the event, Friends of the Library and guests will enjoy wine and cheese, view books and other items — some of which are in poor condition — and talk to curators and conservators. The items available for “adoption” range in price from $100 to about $5,000.

Among the items on display will be a 1938 British picture book by Kathleen Hale, Orlando the Marmalade Cat: A Camping Holiday; an 1837 Philadelphia city directory including names of hotels, bank directors, loan and insurance companies, and churches; and an 1807 English translation of a journal kept by a German mineralogist who introduced a new method of refining silver in Peruvian mines.

The affair is the brainchild of Donald Farren ’58, a retired librarian

and curator of rare books and manuscripts and a member of the Council

of the Friends of the Library. He modeled the event after similar ones

held at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., where he is

a scholar-in-residence. The adoption party, says Farren, will give community

members “an opportunity to see these objects close up and talk with

the curators and conservators who work with them.” ![]()

By K.F.G.

(Paul Éluard. À toute épreuve [title page]. Gravures sur bois de Joan Miró. Geneva: Gérald Cramer [1958]. © Artists’ Rights Society ) |

When poets and artists collaborate

On display at Firestone Library is an exhibition highlighting the artistic

collaborations of French poet Paul Éluard and Catalan artist Joan

Miró. Titled “Notre Livre: À Toute épreuve.

A Collaboration between Joan Miró and Paul Éluard,”

the exhibition features the original 1930 edition of Éluard’s

collection of poetry, À toute épreuve, written after his

wife left him for the artist Salvador Dalí, and the illustrated

1958 edition, above, for which Miró created 79 prints using woodcuts.

(The title of the book is roughly translated as “ready for anything”

or “foolproof.”) The exhibition, which runs through June 29,

includes books resulting from Éluard’s collaborations with

other artists, as well as Miró’s work with other poets. ![]()