|

April 23, 2008: Perspective

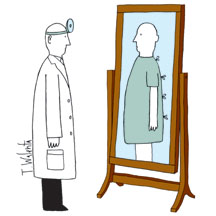

(Illustration: Tomasz Walenta) |

Double

lives

When doctors become patients

By Robert Klitzman ’80

Robert Klitzman ’80 is an associate professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University and the author of six books, most recently, When Doctors Become Patients (Oxford University Press, 2008), from which this essay is adapted.

At 8:30 a.m. on Sept. 11, 2001, from her office on the 105th floor of the World Trade Center, my sister Karen, a member of the Class of 1984, called her best friend. No one ever heard from her again.

Over the next few weeks, I helped organize a memorial service and a fellowship in her name, signed a death certificate, and packed up all of her belongings. Then my body gave out. For three months, I could not sleep. I had a flu that would not leave me. I could not get out of bed and was no longer interested in reading books, seeing movies, or listening to music. Yet I was surprised when friends told me they thought I was depressed.

“No, I’m just sick,” I said, resisting the idea. I was a psychiatrist, but suddenly had physical symptoms of depression and was amazed at the experience — how much it was more bodily than emotional. As never before, I fully appreciated what my patients had to undergo, and how hard it is to put the experience of depression into words.

I went to psychotherapy, memorial events, my synagogue, and for the first time, a Buddhist service. I saw a psychic who claimed to communicate with Karen, though I was wary. I sat in Central Park in the middle of the day, for the first time in my life doing nothing for hours. I thought my training as a psychiatrist would help, but it was quite the opposite. The experience forced me to cross the border from doctor to patient, and taught me how much I did not know.

After several weeks of treatment, my symptoms passed, but I realized that I, as a doctor, would never be the same nor look the same way at the problems patients and their families faced concerning depression or grief.

I wondered how the experience of becoming a patient affected other physicians. And so I set out to interview 70 doctors — male and female, young and old — who became sick with serious disease. I soon saw how, as patients, they drew on their knowledge as doctors; as doctors, many came to incorporate the often-painful lessons they had learned from being on “the other side,” as patients. They had been on both sides of the stethoscope; their contrasting experiences as physicians and patients provided rare insiders’ perspectives on the contemporary medical system.

It was at Princeton that I first read works by the psychoanalyst Carl Jung, who described a paradigm of “wounded healers.” Through awareness of their own injuries and personal suffering, such healers acquire deep wisdom and are able to heal others. Jung traced this concept back to the ancient Greeks, who believed that Asclepius had founded a sanctuary for healing at Epidaurus, based on self-treatment of his wounds. Jung was keenly aware of the potential dangers, as well: A healer may over-identify with patients, feeling the latter’s wounds too acutely, reawakening his or her own.

Ordinarily, people have just one main point of view, yet the doctor-patients who spoke with me had two. Many shuttled back and forth between these dual roles, but over time, each position affected the other. The width and depth of the chasm between these two poles were great. Forced not only to doff their white coats, but to strip bare in cold examining rooms, these doctors were compelled to re-evaluate themselves and their roles and interactions with patients and

colleagues.

“I always thought I was Ms. Compassionate and listened,” said Jennifer, a physician infected with HIV after being stuck by a needle, whom I interviewed about these issues. She glanced down sadly. “It was just so very different to go from one role to the other. I was really much more cavalier and uncaring than I ever would have thought! My eyes were completely opened.” After her diagnosis, she said, she spoke more about end-of-life issues with her own patients.

From medical bureaucracy to hospital food, many of these doctors said they got a new perspective on the health care systems that their own patients confront. Some found it difficult to get second opinions, and wondered how hard that must be for typical patients. A few bemoaned a lack of professionalism among their physicians: “My doctor kept me in the waiting room for 40 minutes!” another doctor told me. “I was driven up the wall! Now, I routinely say to patients, ‘I’m sorry to have kept you waiting.’” A surgeon recalled, “The night before I underwent surgery, my surgeon told me, ‘There’s a 5 percent chance you may die in the operating room.’ That night, I couldn’t sleep. Only later did I realize he could have said instead, ‘There’s a 95 percent chance you may live.’” This doctor had never before realized that those two statements, though statistically the same, elicited such different emotional responses. Many of those who spoke with me had received bad news bluntly, and now saw better ways to deliver it to their own patients.

Aesthetics played far more of a role than these doctors had anticipated, due to the symbolic meanings involved. “My memories now are of the physical environment — the room was ugly, Spartan, inhospitable,” said one. Another complained about the “awful, inedible” hospital food, and the lack of comforts and fresh flowers (she later brought flowers to the clinic she ran). Frustration about the poor quality of the physical plant reinforced helplessness and dependency.

These doctors became far more aware of issues such as spirituality, communication, approaching the end of life, ethics, medical errors, and risks. Almost all attained insight and wisdom, which they offered to patients and family members as practical advice: how to be “better” patients and to communicate more effectively with their doctors and nurses. “Your cancer shouldn’t come back soon,” one ill physician told me his doctor had said to him. But what, he wondered, did that really mean? Through decades of treating patients, he had never thought about how long was “long” or how soon was “soon.” He now became more precise with his patients, and urged them to do the same when speaking to their doctors.

As a result of their experiences, many of the doctors who spoke with me wanted to work to improve medical education. Some joked that medical students should be forced to sleep in patients’ hospital rooms, to experience the disruptions, inconveniences, powerlessness, and humiliations that patients routinely encounter.

While I do not know if empathy can be taught, these doctors’ experiences

can perhaps be more poignant and compelling to other physicians. Frequently,

we dismiss patients’ complaints: “It’s just the patient

griping.” But I join these doctors in arguing, “No, I am one

of you; and these are legitimate criticisms that I, as a patient, now

know.” ![]()