|

Web Exclusives: Under the Ivy

May 9, 2007: By Gregg Lange '70

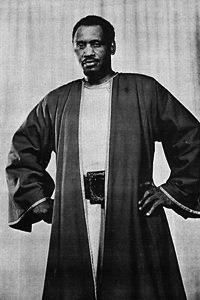

In my more spiritual moments, I often wonder whether Paul Robeson was put on earth in part to keep Princeton humble. The next time you go by FitzRandolph Gate, walk a couple hundred yards down to 110 Witherspoon St., then turn around and look back. Imagine yourself to be 8 years old and living there, a magnet for friends, a well of boundless curiosity and energy, with a voice to move the Lord. Imagine looking up at the closed gates and knowing they were locked, just to be sure you and your family wouldn't come in. Paul Robeson was born in 1898, and his father – a graduate of Lincoln University, long presided over by Princeton alumni – was the pastor of the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church. The public schools of Princeton were segregated, and Paul's modest education until 1907 took place solely with other black kids in town. His older brother, Bill, who also went on to Lincoln and then became a physician, went to high school in Trenton, the closest available – for him. The same would have been true for Paul, but a congregational conflict sent the family away, and by the time he was in high school, he was living up the road in Somerville, where the schools were integrated. He emerged not only as a scholar, vocal soloist, and linguist, heavily encouraged by his father, but also a premiere athlete, and so became generally popular among the students. Planning to go to Lincoln, he heard at the last minute of a competitive exam open to all New Jersey students for a single four-year scholarship to Rutgers, which he won in 1915. He became the third black student to attend Rutgers, and through his four years was the only one on campus. A stunning bass, he was not allowed to sing in the Glee Club. The best athlete on the football team, he was held out of a home game against Washington & Lee in his sophomore year by demand of the visitors, and he was not invited to the year-end team banquets. But he stayed on to become an All-American in his junior and senior years. In all, he earned 12 varsity letters, and one of his favorite wins was a 5-1 baseball triumph over Princeton his senior year. Coming from 110 Witherspoon St., one can imagine why. After writing his thesis on the Fourteenth Amendment, he graduated as valedictorian of the Rutgers Class of 1919, concluding his address:

Could such a man have profited Princeton? Could Princeton have supported and extended his reach? These are not only academic questions, they are troubling and frustrating and, as I said, humbling. After earning a degree at Columbia Law School, Robeson quit the firm that was brave enough to hire him when a white secretary refused to take his dictation. Stymied at law, Robeson went on to become a pre-eminent actor, singer, and proselytizer for equal rights across the world. His lauded performance as Othello with Jose Ferrer '33 still astonishingly holds the duration record for Shakespeare on Broadway; his interpretations of Eugene O'Neill '10 created a sensation. His rendition of "Ol' Man River" in the 1936 film version of the great Show Boat is still regarded as the definitive version of that plaintive cry from the slave world that was supposed to have died 70 years before. His powerful concert performances of traditional Negro spirituals literally were a revelation to most white people who heard them. He spoke and sang in 15 languages. Would such a man have been as valuable to Princeton as Hobey Baker '14, or Jimmy Stewart '32, or Norman Thomas 1905, or Adlai Stevenson '22? Usually an expatriate because of racial limitations on performing in the United States, Robeson became admired in Europe and in the Soviet Union. He developed a weakness for the Stalinist regime; its lip service to the proletariat blinded him to its mass evil, hoping against the evidence that there was a place on Earth where we were brethren. Thus he ended up pursued by J. Edgar Hoover and Joe McCarthy and broken in the '50s, long before his time. Is there in the end something valuable in this tale for Princeton? Remarkably, there is. Robeson's close friend, classmate, and academic rival at Somerville High School, by astonishing coincidence, went to Princeton in 1915 and eventually became dean of the faculty for an unprecedented 21 years, then the University's first provost. Along with Bob Goheen '40, J. Douglas Brown '19 from Somerville prodded Princeton from World War II to its transformation in the 1960s and was the other guy in charge when Princeton hired Carl Fields in 1964. In our next column, we will recall how important that was. But for now, go to YouTube and catch Paul Robeson singing "Ol'

Man River" or "Go Down, Moses." Imagine it in Alexander

Hall, and weep. Have another view of which Princeton basketball team was the University’s best ever? Write to PAW at paw@princeton.edu

|

||

Gregg

Lange '70 is a member of the Princetoniana Committee and the Alumni

Council Committee on Reunions, an Alumni Schools Committee volunteer,

and a trustee of WPRB radio.

Gregg

Lange '70 is a member of the Princetoniana Committee and the Alumni

Council Committee on Reunions, an Alumni Schools Committee volunteer,

and a trustee of WPRB radio.