|

Web Exclusives: Alumni Spotlight May 11, 2005

Looking

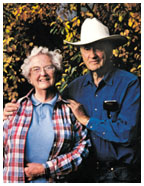

back on life’s adventures Randolph Jenks ’36 has been a homesteader, miner, teacher, ornithologist, bodyguard, business executive, builder, and treasure-hunter. Known as “Pat” because he was born on St. Patrick’s Day, he admits to being “interested in everything.” He also led a life of adventure out West, which in his early adulthood was “still pretty wild.” A New Jersey native, Jenks first headed west at 15, to school in Arizona, because doctors thought the dry climate would relieve his sinus problems. He came back to New Jersey in the fall of 1932 for what turned out to be his first, short stint at Princeton. But by Thanksgiving his sinus condition had resurfaced, and he returned to Arizona. While a student at the University of Arizona in Tucson, Jenks lived alone on his own homesteaded land in the Santa Catalina Mountains, in an adobe house he built, and he pursued ornithological research as the curator of ornithology at the Museum of Northern Arizona. Life was anything but dull in Arizona: Jenks was kidnapped by a gang in Tucson who “used an injection on me such as the lion hunters do on game in Africa,” he says. Jenks awoke after a few hours, he says, saw “some dangerous-looking men,” and bolted out the door. He was later asked to serve as “protector” for the 8-year-old son of William H. Woodin, secretary of the treasury under President Franklin Roosevelt, as “there was a rash of kidnappings in Tucson at the time,” says Jenks, who has detailed his many adventures in two memoirs, Desert Quest (1995) and Leaving the Golden Age of the 1920s for Adventures in the West (2003). Meanwhile, friends at Princeton and his parents had been urging him to pursue his scientific interests at Princeton. He re-enrolled in 1934, having overcome his health problems, and majored in biology. After graduating, he convinced a New York debutante, Julia Post Swan, to marry him and move to his Arizona homestead. “I took her from luxury in the East to an adobe shack in the dry, hot desert,” he says. Eventually, they moved closer to Tucson, where Jenks pursued various enterprises: selling real estate, tutoring, and running a laundry and dry-cleaning service. Adventure called again when his family asked him to protect their gold mine in Mexico’s Sierra Madre from bandits in the 1940s. A group of bandits, led by a woman, “staged raids when we’d take the bullion to the railhead to get to the bank in Chihuahua City,” says Jenks. Unfortunately, he was never able to secure a safe route and the mine was closed. But he never lost his thirst for excitement. He went on several expeditions into Mexico and along the border, seeking lost treasures like those from the legendary gold mine, the Lost Dutchman Mine. But he never did discover buried treasure. Today Jenks has settled into a quieter life with his wife in Tucson.

Instead of looking for treasures or dodging bandits, he is a cattle

rancher. On March 17, he turned 93 and celebrated with his large

family, including one great-great-grandson. “I think I’m

the only one in my class with a great-great-grandson,” he

says. By Caroline Moseley Caroline Moseley is a writer in Princeton, N.J.

|

||