|

Web Exclusives: Alumni Spotlight January 24, 2007: PROFILE: Garrett Hack ’74

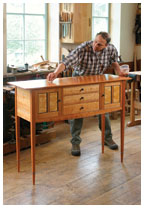

Garrett Hack ’74 doesn’t do things the easy way. In his Thetford Center, Vt., furniture studio, Hack lets the machines stand mostly silent and spends hours upon hours with hand tools that furniture makers have used for centuries: chisels for paring joints to a perfect fit, spokeshaves for creating the curved arms of a chair, dozens upon dozens of planes for making surfaces gleam. “Machines run very little around here. It’s mostly quiet,” says Hack. “Machines can only take you so far. You can’t do the things I’m doing by machine.” Hack, who lives in a tucked-away farmhouse, has made a career out of building elegant, meticulously crafted furniture. His pieces, from side tables and towering chests to cabinets for displaying high-end scotch, take classic Federal forms — simple designs, tapered legs — and give them an edgier look. They are distinguished by their detailed inlays, where one type of wood (like ebony) is set into another. He does not sell his work through stores. Customers come to him, willing to pay up to $15,000 for a single piece. Clients know they might have to wait a while: It can take Hack several months to get something just right. On the side, Hack teaches woodworking, is a contributing editor for Fine Woodworking Magazine, and chairs the New Hampshire Furniture Masters Association. Furniture isn’t the only thing Hack makes — he also built his modern Vermont farmhouse, his studio, his barn, a stone wall, and the wooden cart he attaches to the back of his horse. Hack began to make furniture in high school shop (his first chest of

drawers is in the barn) and majored in civil engineering with a minor in architecture

at Princeton. But he realized he liked “building the things inside the

house better than the building itself.” For him, furniture is art that

also functions — it can be beautiful and comfortable at the same time. By Anne Ruderman ’01 Anne Ruderman ’01 is a graduate student at Yale University.

|

||