|

Web Exclusives: Alumni Spotlight

Posted November 6, 2002: Joel

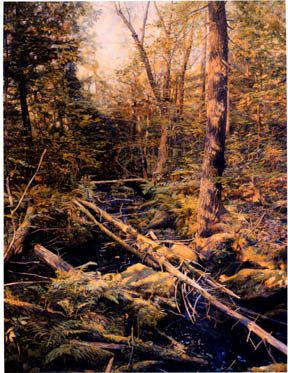

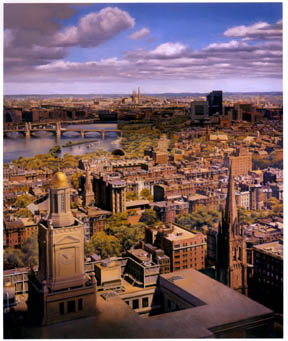

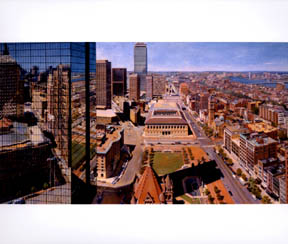

Babb '69: the Canaletto of Boston By James McGregor '68 *75 When artist Joel Babb '69 was at Princeton, he studied abstract painting with George Ortman and modern sculpture with George Segal, he learned patient connoisseurship from John Rupert Martin, and he gained knowledge of the past from Robert Koch, but it was Wen Fong's course in Chinese painting and the concept of modernism that really grabbed him. "Chinese art offered a different attitude toward the past," says Babb. "A traditional Chinese artist was not violating his creative identity by imitating someone else's work. Not only did Chinese painters copy a lot when they were learning how to paint but they also worked in the style of another person as an expressive mode. The artist meditated on nature but at the same time carried on a dialogue with another artist who had lived a hundred years before. In Chinese art revolutions were often carried out under the banner of tradition." When Babb left Princeton, he considered himself an abstract artist, but he took with him a fresh way of looking at art and a newly awakened sense that a contemporary American painter could start a dialogue with the past. He lived for several months in Munich, where he studied the masterpieces of Northern art in the spectacular collections there. Then he moved on to Rome. At the end of his year abroad, he returned to the U.S. and entered the MFA program at The Boston Museum School. Like most American art schools at that time, the Museum School offered few courses in the traditional techniques of naturalistic painting. But Babb solved the problem his own way. He found work as a watchman in the Museum of Fine Arts, and at night in the empty galleries, he studied the collection. By sketching and copying the work there, he slowly mastered the traditional craft that modernism had all but abandoned. Babb's early paintings from that time were meditative, idealized landscapes. But over time, as the urban life took a hold of him, he switched to sharply contoured and meticulously detailed cityscapes. Babb has always approached the city, in this case Boston, from odd angles, wanting to "show the familiar in a new aspect with experimental perspectives." One of the more unusual perspectives can be seen in "Copley Plunge." For this vertiginous view, Babb took photographs looking straight down at the city from the open door of a rented helicopter. The precipitous viewpoint on a Back Bay neighborhood makes the painting a naturalistic Mondrian, where cars, trees, and rooftops are gripped in a rhythmic web-work of abstract squares and rectangles. Others of Babb's paintings survey Boston from among its highest buildings and show it simultaneously from a second vantage point obliquely reflected in mirror-like facades. Some paintings have two vanishing points; a few have even more. In a 20-foot-long painting in the lobby of the Charles Hotel in Cambridge, the viewpoint shifts a full 90 degrees as you walk from one edge to the other. Babb sometimes jokes that he is the Canaletto of Boston, "painting cityscapes in an 18th-century topographical style." Babb's work is in dozens of corporate and institutional collections. Harvard Medical School commissioned him to reconstruct and paint "The First Successful Kidney Transplant," where it hangs in the Countway Library across from a 19th-century painting commemorating the first surgical use of ether. The popularity of his cityscapes kept Babb

from landscapes, but recently he's returned to the forests, rivers,

and coastal islands of his adoptive state of Maine. The work has

earned him an appreciative profile in Downeast Magazine, and this

fall the Olin Art Center at Bates College is hosting a show of his

landscapes. The exhibition, "Intimate Wilderness: Maine Landscapes

of Joel Babb," runs through December 29, 2002.

|

||