|

Web Exclusives: PawPlus

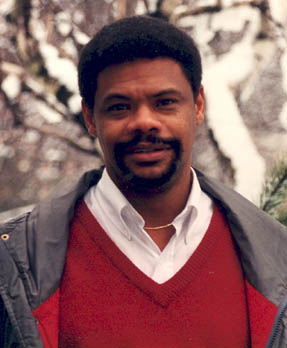

July 2, 2003: By David Marcus '92 William Chester Jordan *73 has taught a lecture course on medieval history at Princeton for more than 20 years, but when he began to write a book surveying the topic, he found that his teaching had lulled him "into a false sense of security. By giving a strong argument in the lectures, you leave out nuances," he says. This winter, Viking published Jordan's Europe in the High Middle Ages, the first volume in a series on European history for educated lay readers. The book covers the period between 1000 and 1350: the era of Gothic architecture and the Crusades, during which Dante and Thomas Aquinas flourished, and in which the modern European nation-state began to emerge. Among other topics, Jordan looks at daily peasant life, the conflict between the Catholic Church and the state, and the devastating effects of the plague in 14th-century Europe. His survey differs from other such studies in two ways, says Jordan. While most books focus on Western Europe, Jordan's work incorporates regions like Poland, Hungary, and Scandinavia. He also discusses the implications of Jewish-Christian relations for state building and the formation of Christian social identity. Although Jordan, a professor of medieval history, director of the Program in Medieval Studies, and author of The Great Famine (1997), used his lecture notes as a blueprint for the book, he had to do substantial work to complete it. He begins his course with the Investiture Controversy, the late 11th- and early 12th-century debate over whether the Catholic Church would have the right to self-determination or would be subject to lay control. But the book starts in the year 1000, so Jordan had to do an immense amount of reading to write the first several chapters. Jordan imported two techniques from his teaching into his writing. He quoted primary sources to give readers a sense of the period, just as he assigns such reading to his students. "One of the things you work against so much is the idea that people in the past were quaint," Jordan says. "Reading 50 pages of Aquinas puts that to rest." He also sketches certain scholarly debates of the era such as the one around the Magna Carta. "I wanted to discuss them enough to suggest that the word definitive should not be in the historian's vocabulary," Jordan says. The Magna Carta averted a brewing conflict between King John and the English nobility, who demanded a charter of liberties as a safeguard against the king's arbitrary behavior. Although it came to be considered a foundational document of English law, Jordan says, it was "hammered out over several days in 1215, with three sides arguing in an effort to prevent a civil war. It's full of ambiguities and badly drafted language." His next book will be a study of Jacques de Thérines, a

professor at the University of Paris and Cistercian monk who was

involved in virtually every major struggle within the Catholic Church

around 1300. "If it works, it could be lively and interesting,"

Jordan said. "If it doesn't, it'll be scholarship." David Marcus '92 is a frequent PAW contributor.

|

||