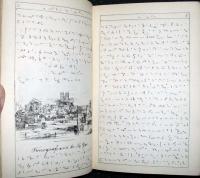

Books written in shorthand began to appear as early as the sixteenth century. But it was the eighteenth-century invention of lithography that provided the ideal medium for their printing, along with books of music and those written in some non-Latin scripts. More than any other individual, it was Sir Isaac Pitman (1813-1897) who was responsible for the writing and distribution of these lithographic books.

Pitman was a great proponent of alternative writing systems. His plan for phonic writing or phonography has dominated the shorthand world since 1830s, while his design for simplified spelling, which he called phonotype, never caught on — unless you count twenty-first-century texting. If Pitman had his way, we would have dropped the k, q, and x long ago.

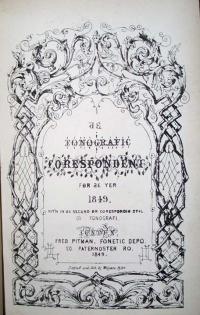

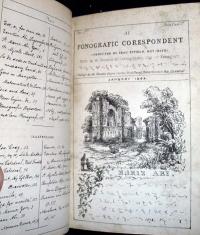

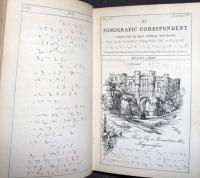

He was a zealot for these writing systems and published dozens of books and journals promoting them, including the Fonographic Korrespondent seen here. Over the years, the journal was also called the Phonographic Correspondent, Fonografic Corispondunt, Fonografic Corispondent and Riportur, Fonografic Corespondent and Reporter, and many other variations.

The text was written by hand on transfer paper, which could be pressed onto a lithographic stone surface alleviating the need to write the text backwards. Some transfers were taken from letterpress type, border elements, and signatures, giving the title pages the look of letterpress books, although they were always printed lithographically.

For more information on fonography, see Michael Twyman, Early Lithographed Books: a study of the design in the and production of improper books in age of the hand press (London: Farrand Press & Private Libraries Association, 1990). Graphic Arts Collection (GA), NE2295 .T99