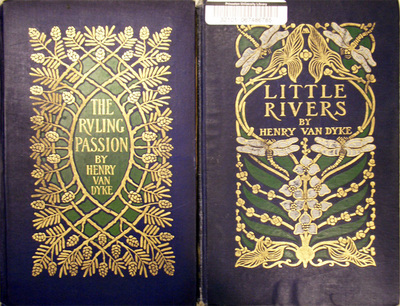

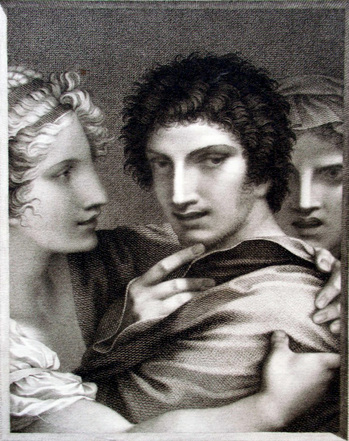

Désiré Magloire Bourneville (1840-1909) and Paul Regnard (1850-1927),

Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière. Service de M. Charcot (Paris: Adrien Delahaye & Co., 1876-1877, 1878). Graphic Arts Collection GAX 2012- in process

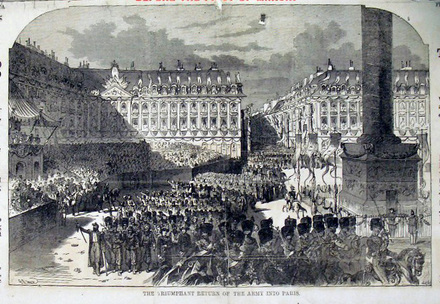

As a young professional Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) served his internship at Salpêtrière, a women’s hospital in Paris used as more of “a warehouse for female outcasts: women who were mad, violent, crippled, chronically ill, mentally retarded, unmarried and pregnant, or simply old and poor.” Charcot called it “that grand asylum of human misery.” [Medical Muses, 2011]

In 1862, Charcot returned to Salpêtrière as chief physician of medical services and transformed it. During his tenure, the hospital grew to house more than 5,000 patients in 100 buildings; the largest institution of its kind in Europe. It had its own farm, bakery, and by 1878, a well-equipped photography studio. (Bellevue Hospital in New York City also had a full photography department.)

Asti Hustvedt writes, “Charcot … brought hysteria, hitherto marginal, into the mainstream. He legitimized the disease by defining it as an inherited neurological disorder, not madness or malingering.” Martin Kemp noted that the doctor’s work was “an unrivaled attempt to create what may be called ‘visual psychology’ —in which imagery and environments played a central role in diagnosis, recording, clinical suggestion, treatment and the design of the patients’ surroundings.”

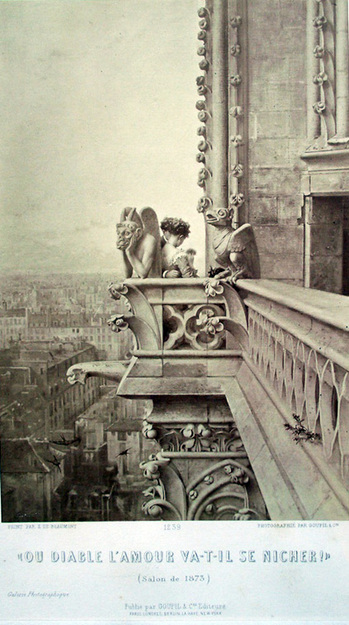

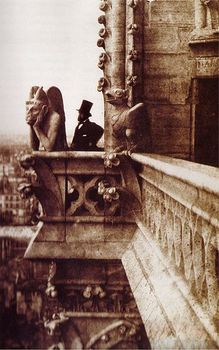

Charcot was deeply influenced by his predecessor at Salpêtrière, Guillaume-Benjamin Duchenne de Boulogne who published his treatise Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine in 1862. Six years earlier, Duchenne had begun photographing his patients, thanks to the help of Adrien Tournachon (Nadar’s brother), as a form of “orthography of the physiognomy in motion.” Charcot began to do the same.

In 1875, he selected as an intern a young psychiatry student named Désiré-Magloire Bourneville, who was also a journalist. Bourneville wrote extensively for medical journals and eventually, published two of his own. Under Charcot, he learned to keep extensive medical histories on the patients, many of which were later published in Iconographie. It is thanks to Bourneville that Charcot’s many accomplishments became known both in his own time and today.

Another intern, Paul Regnard, was hired, in part, for his ability to make photographs. Charcot hoped these would provide visual evidence to support his conviction that hysteria was a real organic disease with particular symptoms. In 1882, photographer Albert Londe (1858-1917) was hired as a chemistry assistant and before long, took over the running of the photography laboratory. Londe published his own study in 1893 entitled La photographie médicale: application aux sciences médicales et physiologiques, dedicated to Charcot.

“The photographs in the Iconographie haunt its pages,” writes Hustvedt, “[they are] the ghosts of women who refuse to be reduced to medical illustrations.”

See also:

Asti Hustvedt, Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2011). Firestone RC339.52.C453 H87 2011

Ann Thomas, Beauty of Another Order: Photography in Science (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, 1997). Marquand Library (SAPH): TR692 .T466 1997

Recent Comments