In 1924, Ralph Waldo Emerson Barton (1891-1931) was asked to serve as an advisory editor to Harold Ross for his new magazine The New Yorker, along with Marc Connelly, George Kaufman, Rea Irvin, Alice Duer Miller, Dorothy Parker, and Alexander Woollcott. These artists and writers were expected to contribute material to be printed anonymously, in exchange for stock, while retaining rights for reprints themselves. In one week alone, in the late 1924s, Barton completed eighty-five drawings. He was at the height of his career and one of the highest paid artists working in New York City. His drawings are, for many, synonymous with the 1920s.

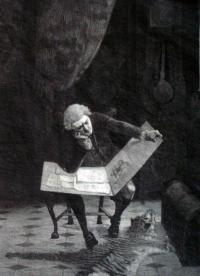

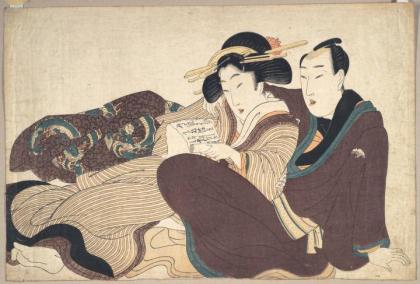

Hundreds, if not thousands, of Barton’s drawings were published unsigned and few survive in their original format. Besides The New Yorker, he worked for Collier’s, The Delineator, Everybody’s magazine, Harper’s Bazaar, Hearst’s International, Judge, Leslie’s Weekly, Liberty, New York Herald Tribune, Photoplay, Puck, Satire, Shadowland, Vanity Fair, and many more. He illustrated many books, including Droll Stories by Honoré de Balzac, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and But Gentlemen Marry Brunettes by Anita Loos, The Tattooed Countess by Carl Van Vechten, and his own God’s Country. He also made one film, at the urging of his friend Charlie Chaplin, entitled Camille: The Fate of a Coquette, starring Paul Robeson, Sinclair Lewis, George Jean Nathan, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Alfred Knopf, Ethel Barrymore, Somerset Maugham, and many of his other friends.

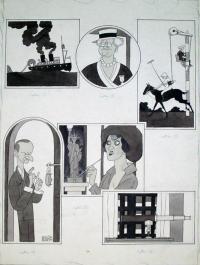

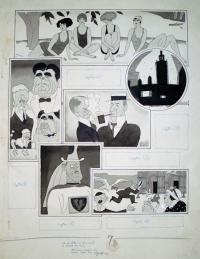

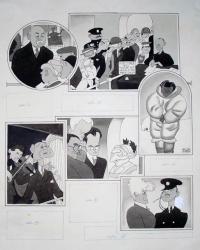

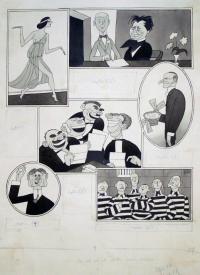

The drawings in the Graphic Arts Division were published in Judge under the section “Judge’s Rotogravure section; The News of the Globe in Pictures by Ralph Barton”. They are not included in any published listing of Barton’s work. We can only assume they are from the 1920s.

When Barton shot himself in 1931, he left two notes. The first, titled “Obit,” was an explanation of his suicide, which he attributed to melancholia. Barton wrote, “No one thing is responsible for this and no one person—except myself. If the gossips insist on something more definite and thrilling as a reason, let them choose my pending appointment with the dentist or the fact that I happened to be painfully short of cash at the moment.” The second note was to his housekeeper, leaving her $35 and an apology that it was all he had left.

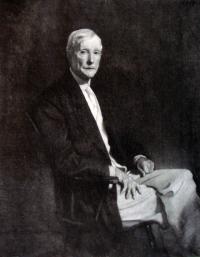

John Updike (1932-2009) selected only a few, favorite artists to write about in The New Yorker, later republished in Just Looking, and one was Ralph Barton. “Barton’s caricatures are not idignant, like Daumier’s, or frenzied, like Gerald Scarfe’s,” he wrote, “they are decoratively descriptive.” Then, Updike quoted Barton speaking of his own work, “It is not the caricaturist’s business to be penetrating; it is his job to put down the figure a man cuts before his fellows in his attempt to conceal the writhings of his soul.”

Later, in a foreword to Bruce Kellner’s biography on Barton, Updike wrote

“In the fury of his life and career Barton was careless of his work; most of his originals are lost, destroyed by him or by the engravers whose indifferent, coarsely screened reproductions are all we have left. …A lost Manhattan and a lost decade live again in the particulars of Barton’s hectic career. The life was less happy than it should have been, considering its achievement; the best of Barton’s art is like a perfect flower, wiry and fluent, blooming in the wilderness of his era’s commercial art.”

Bruce Kellner, The Last Dandy, Ralph Barton: American Artist, 1891-1931 (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, c1991) Firestone Library (F) NC139.B36 K45 1991

John Updike (1932-2009), Just Looking: Essays on Art (New York: Knopf; Distributed by Random House, 1989) Rare Books (Ex) N71 .U64 1989

Recent Comments