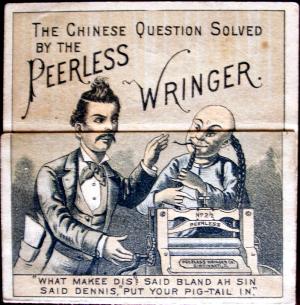

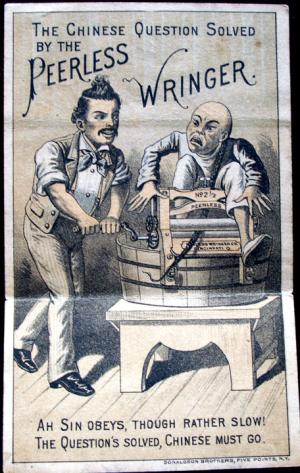

This metamorphosis or transformation card is an advertisement for the Peerless Wringer washing machine, printed in the 1880s by the Donaldson Brothers based in the Five Points (lower Mulberry Street) in New York City. It features Dennis Kearney (1847-1907), an Irish immigrant who settled in San Francisco. The charismatic Kearney was the leader of the Workingmen’s Party of California, whose platform announced, “The Chinese laborer is a curse to our land, is degrading to our morals, is a menace to our lives, and should be restricted and forever abolished, and the Chinese must go.”

Their efforts resulted in the Chinese Exclusion Act, signed into law on May 8, 1882. Chinese immigration was suspended for ten years, including Chinese “skilled and unskilled laborers and Chinese employed in mining” already settled and working in the United States.

On the card, Kearney is seen enticing a Chinese laundry worker named Ah Sin (after Bret Harte’s poem “The Heathen Chinee”) to insert his queue (braid) into the modern washing machine. The text reads, “‘What makee dis?’ said bland Ah Sin. Said Dennis, ‘Put your pig-tail in.’” The lifted flap shows Ah Sin caught in the wringer and finishes the verse, “Ah Sin Obeys! Though rather slow! The Question’s solved, Chinese must go.”

Donaldson Brothers printing company was established by George, Frank, John, and Robert Donaldson in 1872. Their high-speed steam presses produced, among other things, trade and advertising cards with bright chromolithographed images in large quantities. The Donaldsons merged with the American Lithographic Company in 1891 to form one of the largest commercial printing company in New York.

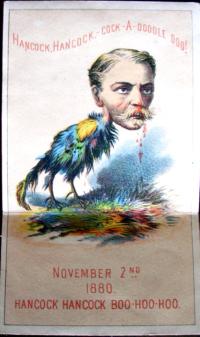

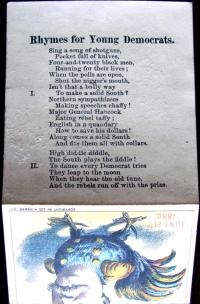

This transformation book was produced for the 1880 presidential campaign of Republican James A. Garfield (1831-1881), running against the Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock (1824-1886). Garfield was a fervent abolitionist. This card not only predicts Hancock’s failure, depicting him as a cock that looses his feathers, but accuses him of racism in the verse on the back. In his campaign, Garfield used this slogan, “Hancock. Hancock. Cock-a-doodle-doo. Hancock. Hancock. Boo-Hoo-Hoo.”

It is curious to find the copyright owned by George H. Hanks, who, in the 1860s, was a Colonel of the 18th Infantry, Corps d’Afrique (a Union corps composed entirely of African-Americans) and later became Superintendent of Negro Labor. I have not found any record of Hanks’s role in Garfield’s campaign.