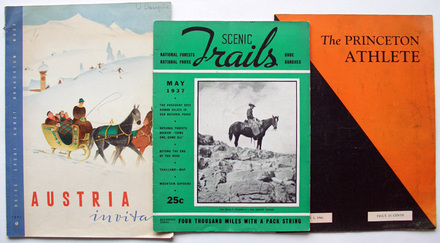

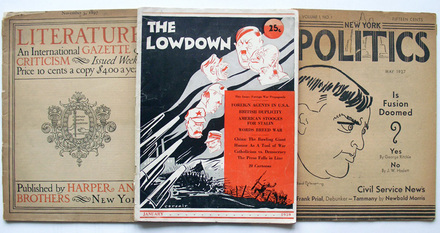

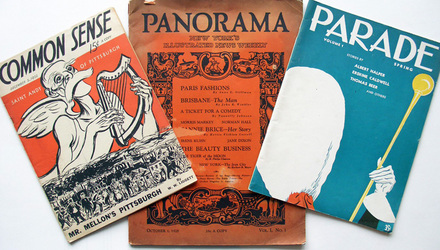

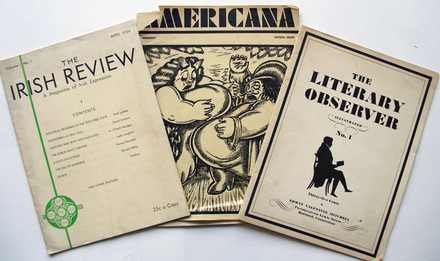

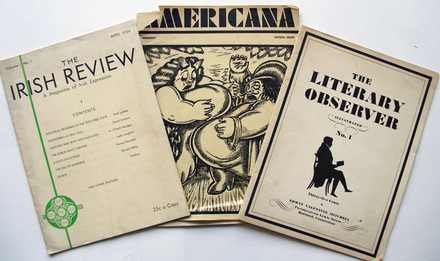

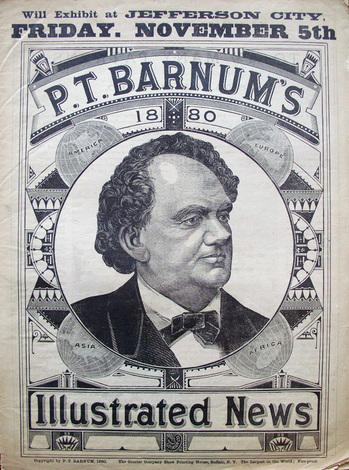

Elmer Adler, former curator of the graphic arts collection, was a connoisseur of publishing. One of the genres he collected was first issues of magazines. This collection is separate from the library’s own runs of serial and includes mostly American titles. Each issue is volume one, number one.

One important exception is Adler’s copy of

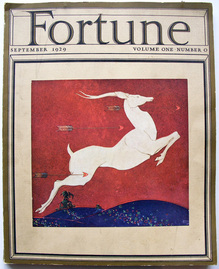

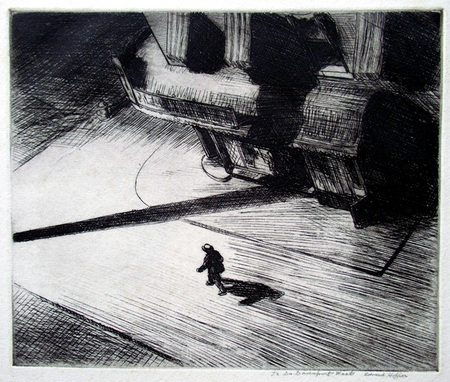

Fortune magazine, which is volume one, number 0. This September 1929 publisher’s dummy includes many of the articles but lacks some of the photographs and has no table of contents. The cover image by Stark Davis (1885-1950) is completely different than the one by T.M. Cleland (1880-1964) used when the magazine debuted in February 1930.

A letter to advertisers included with this issue of Fortune reads in part, “The advertising manager has prevailed upon the editors to issue a few copies of this dummy, the fourth of ten steps in the publishers’ program for the artistic and mechanical evolution of Fortune. It will give advertisers some hint of what Fortune vol. 1 no. 1 will be like when it appears January, 1930.”

Here is a list of the titles represented in Adler’s collection:

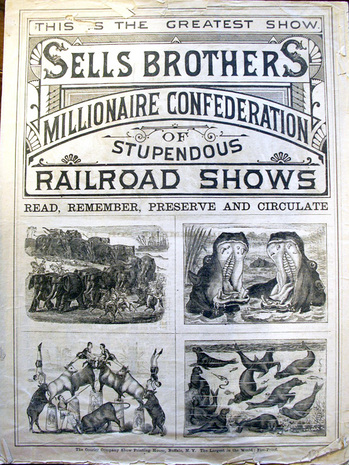

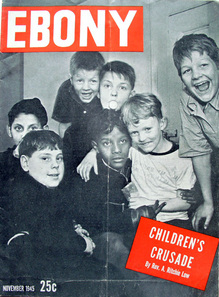

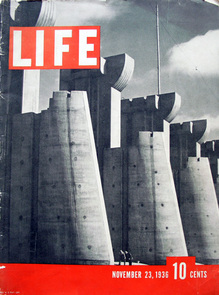

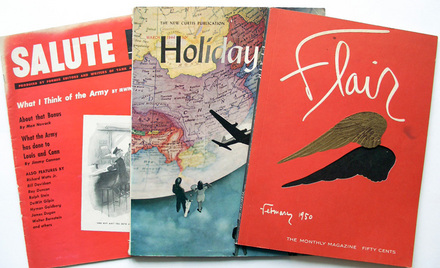

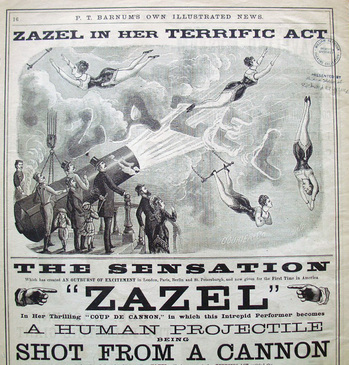

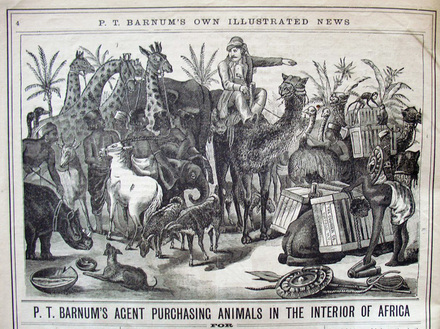

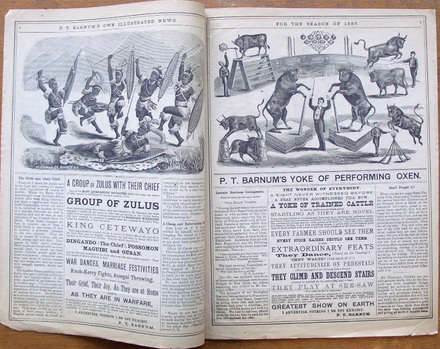

Accordion World, April 1936; American Aviation, June 1, 1937; Americana, February n.d.; Apparel Arts, Christmas 1931; Atom, fall 1945; Atomic and Gas Turbine Progress, October 1945; Austria Invitans, 1951; Bean Home News, v.1 n.d.; Book Collector’s Quarterly, October 1925; Bulletin of Collectors of American Art, May 1938; Common Sense, December 5, 1932; Creative Typography News, October 1950; Ebony, November 1945; Esquire, autumn 1933; Fascination, February 1946; Flair, February 1950; Fortune, volume 1, no. 0, 1929 (prepublication); Gentle Reader, December 1931; Gilcrafter, December 1938; Harkness Hoot (Yale), October 1, 1930; Holiday, March 1946; Irish Review, April 1934; Island, June 15, 1931; Junior Bazaar, November 1945; Letters (New Hope), spring 1935; Life, November 23, 1936; Linonia, May 1925; Literary Observer Illustrated, April/May 1934; Literature: the International Gazette of Criticism, November 5, 1897; Lowdown, January 1939; Magazine World, November 1944; New Atlantis, October 1933; Panorama, October 1, 1928; Parade, spring [1937]; Princeton Athlete, October 3, 1941; Reading and Collecting, December 1936; Ringmaster, May 1936; Salute, April 1946; Scenic Trails, May 1937; Social Frontier, October 1934; Technocracy Review, February 1933; Typography (Shenval Press), n.d.; Warren Standard, 1924

Recent Comments