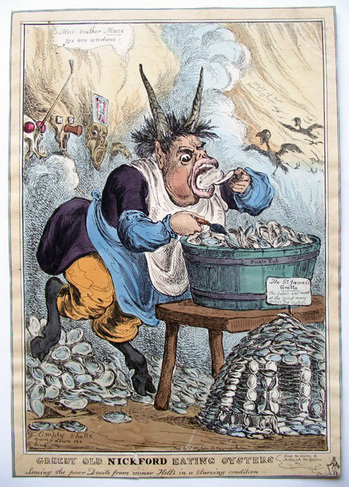

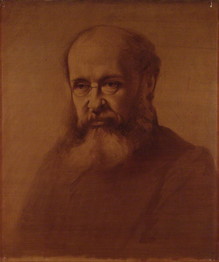

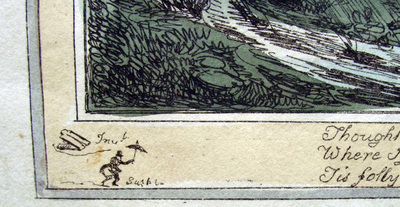

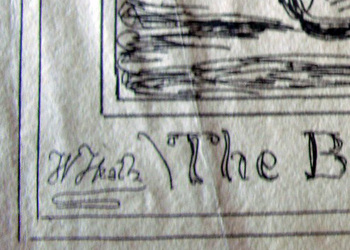

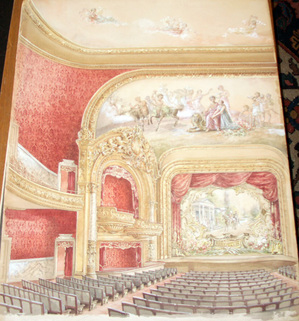

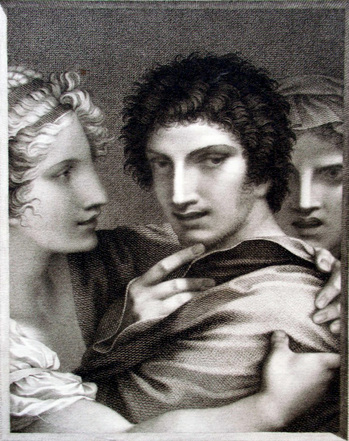

Emily Brontë (1818-1848), Guwald Tower, Haddington, 8 December 1832. Pencil on paper. Inscription by Ellen Nussey. 164 x 149 mm. Robert H. Taylor Collection (RHT), Rare Books and Special Collections. Gift of Robert H. Taylor, Class of 1930.

Quote from Christine Anne Alexander and Jane Sellars, The Art of the Brontës (Cambridge [Eng.]: Cambridge University Press, 1995). (SA) N6797.B758 A4 1995

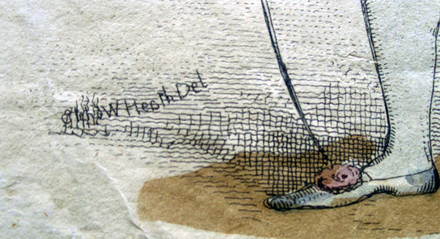

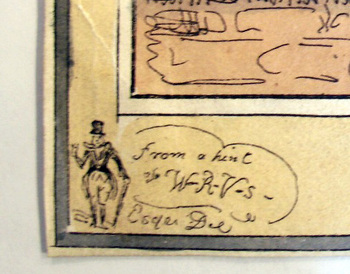

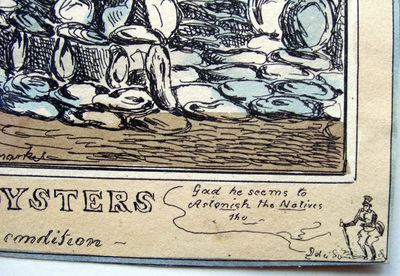

“This drawing is identical (except for very minor stylistic differences) to one by Charlotte Brontë, entitled ‘Guwald Tower Haddington’ and made as an art exercise while she was a pupil at Roe Head in June 1831. Emily’s signature on this second drawing is genuine; yet it is curious that it has been inscribed ‘Miss Brontë’, a nineteenth century formality usually reserved for the eldest daughter of a family, the younger ones signing only with their Christian names. It appears that Ellen Nussey failed to see Emily’s minuscule signature, written in faint pencil and tucked away in an unusual place close to the actual drawing.”

“Ellen would have remembered Charlotte doing the same drawing at School and, at a later date, attributed it to her, also recording the date and place of execution from memory. It is possible the dating is based on a similar drawing by Ellen herself, made as a school exercise from the same original print, at the same time as Charlotte’s copy. Emily probably copied Charlotte’s drawing at home, some time after Charlotte left Roe head in May 1832. Emily herself did not attend the school until 29 July 1835, staying there for less than three months.”

Recent Comments