On October 11, 1865, several hundred native Jamaicans marched into the town of Morant Bay, the capital of the predominately sugar-growing parish of St. Thomas, to demonstrate against injustices. Several members of the crowd, on both sides, were killed. In the days that followed, the British Army was called in and over 500 people were murdered along with hundreds wounded.

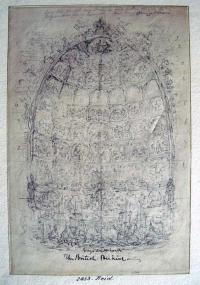

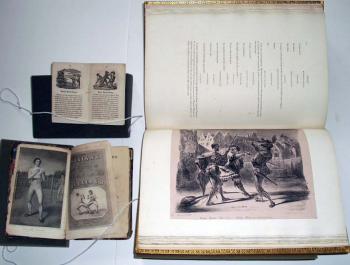

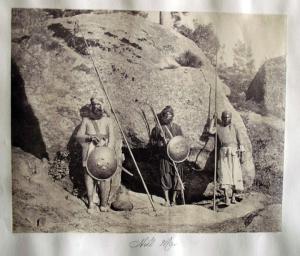

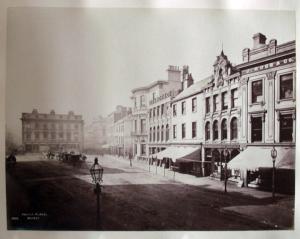

We recently acquired an album with 165 rare albumen photographs: 59 of the Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (1865), 32 photographs of the Indian Northwest Frontier Hazara Campaign (1867-1870), and 64 others depicting Malta, Ireland, Guernsey, and elsewhere. The prints are primarily by unidentified amateur photographers, although there are 8 by Samuel Bourne, 5 by G. Sommer, 3 by William Lawrence, several by Francis Frith.

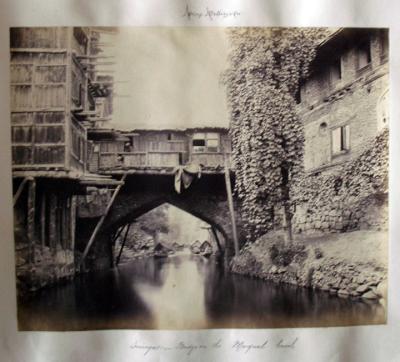

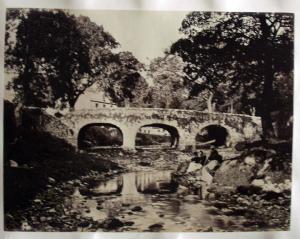

This post will describe the 59 photographs relating to the 1865 Morant Bay Rebellion and future posts will deal with the other sections. The album’s careful compilation includes detailed notes of the people, places, and dates relevant to each photograph. It may be the work of a surgeon in the British Army, Alexander Dudgeon Gulland, MD Edinburgh University, who appears in the album. Appointed Staff Assistant Surgeon in 1854, he served with the 6th Foot which was in Jamaica in 1865 and is listed as having been in China from 1860-62 and Hazara in the Northwest Frontier in 1868 (See: Hart’s Army Lists and Returns Relating to Medical Officers (Army) 1854). The Jamaica section of this album begins with photographs of the Morant Bay military base including a view from the Surgeon’s Quarters and general views of the area to set the scene.

My thanks to Dr. Mimi Sheller, Professor of Sociology, Director, Center for Mobilities Research and Policy Department of Culture and Communication Drexel University, for the following summary of these events.

The events at Morant Bay in 1865 followed on the heels a period of public meetings known as the Underhill Meetings, and peaceful expression of grievances through petitions. Complaints included a series of economic issues related to wages, land tenure, access to markets, and labor rights; political issues related to unfair taxation, no justice in the courts, and elite-biased government policies; and civil issues that included voting rights, and access to healthcare, education, and land. In that sense it was not a riot so much as a social movement, which was rejected by the Governor and finally turned to violence against the representatives of the local government.

Here is a basic description of the facts of what took place before the government sent in military reinforcements to “suppress” the rebellion. During a trial for trespass held in the Morant Bay Court House on the 7th of October 1865, James Geoghagan disrupted proceedings by shouting that the defendant should not have to pay the costs. He was ordered out of the court. When he did not go quietly the Judge ordered his arrest. However, his sister Isabella challenged the police, and when they got outside a “mob” including the Native Baptist deacon Paul Bogle and some of his followers from the hamlet of Stony Gut rescued him from the police. The following day the police went up to Stony Gut to arrest those involved, but the policemen were instead captured and made to swear an oath to “cleave to the black”. To continue reading Dr. Sheller’s description, click on the extended entry link below.

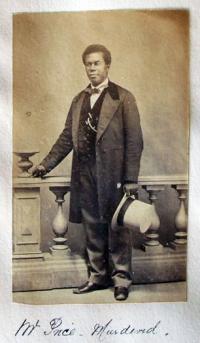

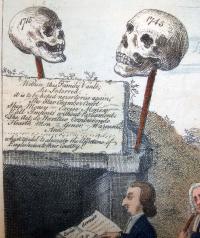

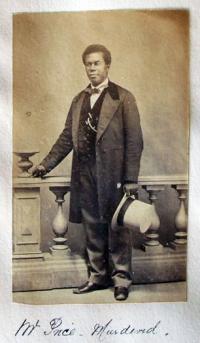

Portraits of key figures from the rebellion tell more of the story. Among them are a

page of portraits of “The Victims of the Jamaica Rebellion of 1865”, a portrait of George William Gordon who is now considered a Jamaican national hero, portraits of unidentified Jamaican natives, and of British Army officers. Listed among the victims are not only those who were murdered but also those in the colonial government who were later tried for murder and acquitted.

It is probable that these portraits were gathered after the rebellion and some may have been taken by the only commercial studio we can identify in Jamaica at the time, run by Adolphe Duperly (1801-1865) and taken over by his son, Armond.

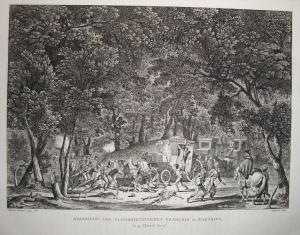

Two small photographs of Jamaican Maroons, including one of Maroons in

camouflage with Colonel Fyfe, reflect an interesting social dynamic in the rebellion.

Originally runaway slaves who set up communities that engaged in guerrilla warfare

against the British, the Maroons eventually cooperated with the British authorities

after they started to deport them and confiscate their land in 1796. Used to suppress

slave revolts until 1838, they were also used to suppress the 1865 rebellion.

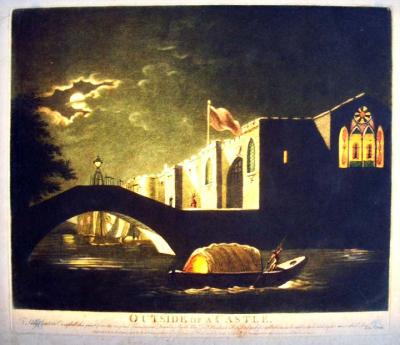

For more information, see “The Town of Morant Bay, Morant Bay, Jamaica,” Harper’s Weekly, December 23, 1865.

“Morant Bay, Jamaica, the Scene of the Negro Insurrection,” The Illustrated London News, November 25, 1865.

Gad Heuman, The Killing Time, The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica (London: Macmillan, 1994) Firestone F1866.H48 1994b

Arvel B. Erickson, “Empire or Anarchy: The Jamaica Rebellion of 1865,” The Journal of Negro History, 44, no. 2 (April 1959): 99-122.

Henry Bleby, The Reign of Terror: a Narrative of Facts concerning Ex-Governor Eyre, George William Gordon, and the Jamaica Atrocities (London: s.n., 1868). Firestone HF 1569.E53

Recent Comments